Doctors have found evidence of rape in the woman who was gang-raped over not voting for ‘boat’ in Noakhali’s Subarnachar Upazila.

Dr Md Khalil Ullah, the superintendent of Noakhali General Hospital, gave the confirmation to our local correspondent this afternoon.

“The test report will be handed over to police today,” he said.

The woman who is a mother of four, was gang raped allegedly by 10-12 ruling party Awami League men on the midnight of election day.

News of her rape has rocked Bangladesh, sparking protests in Dhaka and elsewhere and drawn condemnations all over the social media.

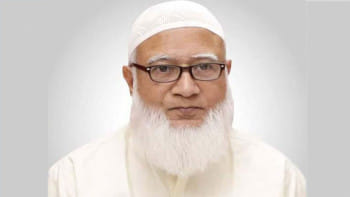

RUHUL AMIN ARRESTED

Since the incident four days ago, five people have been arrested so far including the key accused and “the man who ordered the rape” Ruhul Amin.

In the early hours today, police in separate drives arrested two people including a local Awami League leader from Shenbagh and Sadarupazilas of Noakhali.

The arrestees are Ruhul Amin, former member of Charjubli union parishad and also publicity affairs secretary of Subarnachar unit of Awami League, and Ibrahim Khalil Bechu, said Nizam Uddin, officer-in-charge of Char Jabbar Police Station.

OC Nizam said, “We made the arrest as we found Ruhul’s involvement with the rape incident though his name was not included in the case”.

READ MORE: Mother of four 'gang-raped by AL men'

Earlier, police arrested Badsha Alam from Charbajuli on Tuesday while prime accused Sohel from Cumilla district and Md Swapan from Ramgati upazila yesterday.

WHAT HAPPENED ON THAT DAY?

The 35-year-old woman said some 10-12 men carrying sticks entered her home by cutting the surrounding fence after the midnight on December 31. They tied her CNG-run auto-rickshaw driver husband and four children with ropes.

“They took me outside and raped me,” she said adding that the rapists threatened to kill her husband and children and torch their house if she told anyone about the rape.

The victim's husband, who was also injured, said the criminals left around 4:00am after beating his wife unconscious and taking Tk 40,000, some gold ornaments and other valuables with them.

ALSO READ: Nine sued except 'who ordered it'

Soon after the alleged rapists left, the victim's husband and children cried for help. At this, the neighbours came and rescued them.”

“At first, a village doctor was called. But as she [the victim] was still bleeding, she was taken to Noakhali General Hospital at noon,” said one of the neighbours, wishing anonymity.

Shyamol Kumar Devnath, of the emergency department at the hospital, said they found evidence of rape. There were also injury marks on different parts of the body, he said.

The husband said the victim went to cast her vote at Char Jubilee-14 Government Primary School centre around 11:00am on Sunday. She took the ballot paper from the assistant presiding officer and went to a booth.

During that time, Ruhul, an Awami League man, allegedly insisted her to vote for the “boat”. He allegedly tried to snatch the ballot paper as she said she would vote for the “sheaf of paddy”. But the victim put the paper inside the box.

READ MORE: Noakhali Gang Rape: Key accused, another held

This made Ruhul furious and he threatened her, he said.

WHAT DID THE VICTIM SAY ABOUT REASON BEHIND THE INCIDENT?

The 35-year-old woman, who was being treated at Noakhali General Hospital with severe injuries, claimed that she was raped for voting for “sheaf of paddy”, the electoral symbol of the BNP, during Sunday's national polls.

The woman alleged the rapists were accomplices of Ruhul Amin. “They had repeatedly insisted that I should vote for boat [the AL's symbol] but I cast my ballot for 'sheaf of paddy',” she said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.