Special Supplement

Second International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice

International Tribunals: Lessons for Bangladesh

Dr. David Matas

|

Syed Zakir Hossain |

AS Bangladesh starts on the work of justice for the crimes of 1971, the international experience merits attention. The international community has created a number of tribunals in recent years to prosecute international crimes, eight in all - the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (1993), the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (1994), the International Criminal Court (1998, entry into force 2002), the Special Panels of the Dili District Court in East Timor (2000), the Special Court for Sierra Leone (2000), the Internationalized Courts for Kosovo (2000), the Extraordinary Chambers in the courts of Cambodia (2004), and the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (2007). All of these provide relevant experience in dealing with international crimes. Bangladesh has lost thirty-eight years in establishing a legal regime to bring perpetrators of international crimes to justice.

Bangladesh has signed and should ratify the Statute of the International Criminal Court. However, the International Criminal Court has jurisdiction only for crimes committed after the entry into force of the statute of the court, which was July 1, 2002. So that Court is not an option for the 1971 crimes.

Bangladesh enacted a law in 1973 to bring to justice the perpetrators of the 1971 genocide, the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act of 1973. That law was not implemented then for political reasons. I am pleased to see that the Government of Bangladesh has decided now to implement that law, to establish the tribunals for which the law was enacted.

I want to draw on that experience to attempt to answer three questions. How do we combat delay, so that the Bangladesh cases not only get started, but actually get finished in a timely fashion? Second, how to approach cases strategically so that the Bangladesh Tribunals do not get bogged down? Third, how do we fill in gaps in the Bangladesh legal structure?

Combating delay

Trials for violation of international law bring to bear issues not found with ordinary crimes. International crimes are massive. There are a myriad of perpetrators. The law is complex.

The Bangladesh International Crimes (Tribunals) Act, 1973 in section 11 (2) provides that a Tribunal shall confine the trial to an expeditious hearing of the issues raised by the charges and take measures to prevent any action which may cause unreasonable delay. I have five suggestions to make about the mechanics of trials, drawn from the international experience, to prevent unreasonable delay. The suggestions I propose do not require an amendment to the 1973 law.

1) Preventing interlocutory appeals: A primary cause of delays in international criminal trials has been interlocutory appeals. Trials inevitably involve a myriad of interim rulings about procedure and evidence. If each ruling can be appealed and the trial held in abeyance in the meantime, the trial can take forever.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, which faced this problem, resolved it with a rule that interlocutory appeals were impossible with two exceptions. One was motions challenging jurisdiction. The other was cases where certification has been granted by the Trial Chamber.

The Trial Chamber was given the power to grant certification if two criteria were met. One was that the decision involves an issue which would significantly affect the outcome. The other was that an immediate resolution of the issue by the Appeals Chamber might advance the proceedings. The Bangladesh International Crimes (Tribunals) Act, 1973 provides for a right of appeal to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh against conviction and sentence. A recent amendment gave the prosecution a right of appeal against acquittal. These provisions do not address directly the issue of interlocutory appeals.

2) Written witness statements: Another way in which time could be saved is to allow witness evidence to be filed in court through written statements, rather than require witnesses to testify in open court. Again, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia provides an example.

Factors in favour of admitting evidence in the form of a written statement or transcript include that the evidence:

(a) is similar to that other witnesses will give or have given in oral testimony;

(b) relates to relevant historical, political or military background;

(c) consists of a general or statistical analysis of the ethnic composition of the population in the places to which the indictment relates;

(d) concerns the impact of crimes upon victims;

(e) relates to issues of the character of the accused; or

(f) relates to factors to be taken into account in determining sentence.

The Bangladesh International Crimes (Tribunals) Act, 1973 allows for written statements from a witness, recorded by a Magistrate or an Investigation Officer, who, at the time of the trial, is dead or whose attendance cannot be procured without an amount of delay or expense which the Tribunal considers unreasonable [section 19 (2)]. This provision does not go as far as the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia provision.

3) Judicial notice of previously adjudicated facts: A third time saver is a robust doctrine of judicial notice to avoid repetition. The rules of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia now provide that a Trial Chamber may decide to take judicial notice of adjudicated facts or documentary evidence from other proceedings of the Tribunal relating to matters at issue in the current proceedings. This taking judicial notice of previously adjudicated facts is an innovation introduced specifically for international tribunals.

The Bangladesh statute provides that a Tribunal shall take judicial notice of facts of common knowledge, official government documents, reports of the United Nations and its subsidiary agencies and other international bodies including non?governmental organisations [section 19 (3) and 4]. There is no express provision for taking judicial notice of previously adjudicated facts.

4) Limiting witnesses: A fourth time saver is allowing the Court to limit the number of witnesses the prosecution can bring and the time available over all to present its evidence. This rule was introduced into the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia as a result of the experience through which the Tribunal lived. The rules now provide that the Trial Chamber, "shall determine the number of witnesses the Prosecutor may call; and the time available to the Prosecutor for presenting evidence."

5) Limiting charges: A fifth manner of saving time is given the Court the power to limit charges against the accused. One has to remember that a criminal tribunal bringing to justice perpetrators of international crimes and a truth commission are different. These trials are not meant to compile historical records but exist to realize justice, to determine the guilt or innocence of individual accused.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia found that prosecutors were trying to do too much, that they were inclined to prosecute everyone against whom there was compelling evidence of guilt for every crime which has been committed, partly because that is what the victims wanted. Yet, the crimes were so massive that realizing such an ambition was unrealistic.

The Court, accordingly, amended the rules to give the Trial Chamber power to fix the number of crime sites or incidents comprised in charges about which evidence may be presented by the Prosecutor. The Court also gave the Trial Chamber the power to direct the Prosecutor to proceed on some counts in the indictment and not others.

Choosing cases strategically

The prosecution will have to choose cases strategically. There is likely to be a wealth of cases from which to choose. Proceeding all at once with every possible case is likely to be unmanageable. Criteria need to be developed for case selection. The quality of the evidence available is an obvious criterion. But it should not be the only one.

Also important is the extent and nature of involvement of the accused in the act. Accused directly responsible for grievous actions should be given priority over those who merely aided and abetted.

Higher-level accused should be given priority over lower level accused. There may be a temptation to start the cases with hands on perpetrators in order to build up evidence for those at higher levels. The trouble with that strategy is that the tribunal can become bogged down in those cases. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia fell prey to that difficulty.

Some jurisdictions prosecuting perpetrators of international crimes write this limitation into their governing statute. The Cambodian legislation limits the scope of the investigation "to senior leaders of Democratic Kampuchea and those who were most responsible for the crimes". The Sierra Leone Special Court has jurisdiction over leaders who threatened the establishment and implementation of the peace process while committing such crimes.

Because, in the case of Bangladesh, the crimes occurred thirty eight years ago, many of the most senior perpetrators have died. At this late date, for the most part, there will be only junior perpetrators available for prosecution. Even amongst these junior perpetrators, though, there will be degrees of responsibility and status at the time of the crimes which should be borne in mind when choosing who to prosecute.

Specific issues

There are number of issues which need to be addressed about which the Bangladesh statute is silent. A fully operational will have to come to grips with these issues. The current Bangladesh statute, the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act of 1973 is a useful framework. For the trials to take place, the framework will have to be filled out.

This is by no means a comprehensive list. But in the time available, I want to address four specific issues: age of accused, relationship with other courts, witness and victim protection and the treatment of subordinates.

1) Age of accused: The Bangladesh statute is silent on the age jurisdiction of the Tribunals. For Sierra Leone, the relevant age is 15. For the International Criminal Court, the age is higher.

2) Relationship with other courts: There has to be a decision about the relationship of the Bangladeshi International Crimes Tribunals with other Bangladeshi courts. Cases are now being launched in the regular courts to bring to justice perpetrators of the 1971 genocide. What happens to those cases once the Bangladeshi International Crimes Tribunals get going?

In the case of Sierra Leone, jurisdiction is concurrent, with primacy going to the international tribunal. There is a similar provision for Lebanon, for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. For East Timor, for crimes committed during the relevant period, the jurisdiction of the Special Panels was exclusive.

A related issue is double jeopardy. Suppose the regular courts have decided a case and the prosecutor wants to bring the accused to a Bangladeshi International Crimes Tribunal or the reverse.

The Sierra Leone tribunal statute provides that a person tried by the international court can not be tried again by the national court for the same offence. A person tried by a national court may however be tried again by the international court where either the act was characterized in the national court as an ordinary crime or the national court proceedings were not impartial or not independent or were designed to shield the individual or the charge was not diligently prosecuted.

In a case where an international prosecution proceeds despite a national court conviction, the international court has to take into account the national court sentence when imposing its own sentence.

3) Witness and victim protection: The Bangladesh statute says nothing on witness and victim protection. Yet, it is a crucial issue for international crimes.

All of the international tribunals address this issue even if only cursorily. The most elaborate is the statute of the International Criminal Court which provides that, as an exception to the principle of public hearings, the Chambers of the Court may, to protect victims and witnesses or an accused, conduct any part of the proceedings in camera or allow the presentation of evidence by electronic or other special means. Another provision states that where the disclosure of evidence or information may lead to the grave endangerment of the security of a witness or his or her family, the Prosecutor may, for the purposes of any proceedings conducted prior to the commencement of the trial, withhold such evidence or information and instead submit a summary.

4) Superior orders: The Bangladesh statute has a provision on the responsibility of superiors but not of subordinates. Different international tribunals have different provisions dealing with the defense of superior orders. For the Sierra Leone Special Court, a superior order is not a defence to a prosecution but it may be pleaded in mitigation of sentence. There are similar provisions for East Timor, the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, and Lebanon. The International Criminal Court statute in contrast provides that superior orders may be a defence where three criteria are met:

(a) The person was under a legal obligation to obey orders of the Government or the superior in question;

(b) The person did not know that the order was unlawful; and

(c) The order was not manifestly unlawful.

Conclusion

Bangladesh has waited far too long to bring the perpetrators of the 1971 crimes to justice. But one advantage of that wait is that many other international tribunals have sprung up in the meantime and gone about their work. They have accumulated experience from which Bangladesh can learn. Their experience will make the work of the International Crimes Tribunals of Bangladesh easier. Bangladesh should make every effort to benefit from that experience.

Dr. David Matas is an international human rights lawyer based in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

The works need to be done

Highlights of the two-day International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice

|

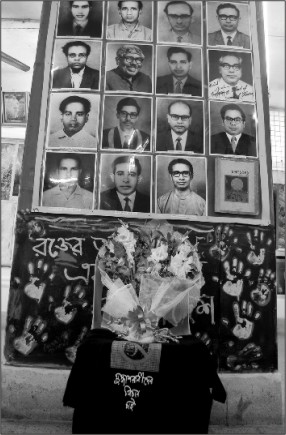

Law Minister Shafique Ahmed speaks as the chief guest at the inaugural of "Second International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice" at Cirdap auditorium in the city. photo: star

|

THE two-day International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice ended with a clarion call to all nation and concerned international communities to work towards ensuring that after long delay of 38 years the process of trial of the perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes in Bangladesh be met with success. The conference highlighted the importance of undertaking multifarious activities involving various sections of the population so that truth and justice prevail. International legal experts, academics and rights activists from various countries including Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, Cambodia, Germany and Canada attended the conference. Besides papers were presented by academics and activists from Pakistan, Australia and UK as well as international organisation like International Centre for Transitional Justice. More than 120 national participants also joined at conference.

The thoughtful presentations and open discussions highlighted the experiences of the world community in organising various trials of the crimes of genocide which would be useful for Bangladesh. Based on the international experiences of such tribunals many practical measures were suggested. The speakers also emphasised on the methodology of documentation, specially in the collection of testimonies and recording the suffering of women. The issue of victims right was a recurrent feature of the discussion. The Cambodian participants dwelt on the work of Victims Unit in the Cambodian Court and emphasised on victim's right for remedies and reparation. Mr. Helmut Scholz, a Member of the European Parliament has drawn attention to the broader dimension of the trial which calls for a holistic approach of social and political rights along with legal measures. Dr. David Matas, an International Human Rights Lawyer, from Canada threw light on the measures which can be taken to prevent unreasonable delays in International Criminal Trials.

In all ten papers were presented by foreign participants and there were eight papers by local participants. In his key-note address Barrister Shafique Ahmed, Minister for Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs explained the tragic political developments behind the long delay in ensuring justice and the recent changes brought by the people and the Govt. to initiate the justice process.

The Conference adopted a resolution calling for the ratification of the International Criminal Court (ICC) statute by the Govt. In another resolution October 21, 2009, has been declared as the “International Day to Remember and Renew the Commitment for Peace” as on that particular day in 1971 Oxfam published the book “The Testimony of Sixty” depicting plight of the distressed people of Bangladesh and delivered it to various heads of the Govt. As an expression of gratitude of our people the facsimile edition of the book will be delivered on the same day this year to the respective governments along with an appeal of solidarity with the trial of the perpetrators of genocide initiated by Bangladesh.

The Conference has opened up the possibility to develop various networks and build alliances with different national and international organisations working with same objectives. During the conference the President of Kean University of New Jersey, USA Dr. Dowd Farahi sent a video message expressing their support to the endeavours to address the human rights violations. He informed the audience that the university will organise a conference on “Bangladesh 1971” in October, 2009.

In the declaration the Conference expressed its approval for the process which have been initiated for the trials and highlighted the importance of learning from the experience and expertise of other tribunals and institutions.

In all the Conference opened up greater opportunities to work with all humanity to usher in a new era of truth, justice and peace ending impunity for the perpetrators of genocide.

Mofidul Hoque

Coordinator, Second International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice.

Declaration of the second International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice

Dhaka, Bangladesh, July 31, 2009

The Second International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice was held in Dhaka, Bangladesh on July 30 and 31, 2009. The Conference was held at a time when the demand for the trials of the perpetrators of genocide and war crimes in 1971 has become alive again in the public domain, especially amongst the younger generation and demands are being raised so that that the brutalities and the trauma of the 1971 Genocide is recognized in the various international fora, so that the lessons of the Bangladesh Genocide may help to prevent other genocides. The holding of the Conference was also significant in the context that the younger generation in Bangladesh has given the demands for the trial their unequivocal endorsement through the national election of December, 2008. The government on the other hand, has given the priority which the trials deserve, to have taken it up in the first session of the new Parliament where it was unanimously accepted by all the parties. The 1973 International Crimes (Tribunal) Act was also amended by the Parliament to make it suitable for holding the trial in the changed circumstances of the day. It is hoped that the Tribunal will be formed soon, the prosecutors appointed and the investigative agencies constituted.

The Second International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice was held in Dhaka, Bangladesh on July 30 and 31, 2009. The Conference was held at a time when the demand for the trials of the perpetrators of genocide and war crimes in 1971 has become alive again in the public domain, especially amongst the younger generation and demands are being raised so that that the brutalities and the trauma of the 1971 Genocide is recognized in the various international fora, so that the lessons of the Bangladesh Genocide may help to prevent other genocides. The holding of the Conference was also significant in the context that the younger generation in Bangladesh has given the demands for the trial their unequivocal endorsement through the national election of December, 2008. The government on the other hand, has given the priority which the trials deserve, to have taken it up in the first session of the new Parliament where it was unanimously accepted by all the parties. The 1973 International Crimes (Tribunal) Act was also amended by the Parliament to make it suitable for holding the trial in the changed circumstances of the day. It is hoped that the Tribunal will be formed soon, the prosecutors appointed and the investigative agencies constituted.

The Conference expresses its approval for the processes which have been initiated for the trial. The Conference also recommends that the nation take lessons from the experience and expertise that are available from the other Tribunals and institutions, especially when formulating the rules and procedures of the above 1973 Tribunal.

The Conference also highlights the need to take supportive and complementary actions and programmes such as the memorialisation, collection and processing of the testimonies given, addressing the issues of the victims' suffering, recognition of the victims rights and most importantly, ensure the broad involvement of the community with the trial process.

The Conference also recognizes that at this important juncture, Bangladesh needs to learn from the experiences which other countries have gained about concepts such as dealing with Transitional and Social Justice and the ways and means to address the complexities in the post-conflict society. Important amongst them are issues of trauma suffering of women, reparation, witness protection, extradition, trials in other countries etc. which would need to be studied further.

The Conference reiterates that it will make efforts to promote research on genocides, particularly on the Bangladesh Genocide and undertakes to promote the setting up of centers of Genocide Studies both at home and abroad. It will encourage other institutions to take up programmes so the issue of the trial stays alive in the public forum.

The Conference also highlights the need to establish various networks and build alliances both nationally and internationally with other organizations having the same objectives, in order to exchange ideas with them during and after the trial.

The Conference calls upon the media and the civil society within the country and abroad to launch a campaign for the universal recognition, especially in the UN, of the Bangladesh Genocide 1971.

Narratives of sexual violence of the war of 1971

Nayanika Mookherjee

This article is based on my fourteen-month fieldwork in Bangladesh on the public memories of sexual violence of 1971 undertaken between 1997-1998 and 2002-2003.

This article is based on my fourteen-month fieldwork in Bangladesh on the public memories of sexual violence of 1971 undertaken between 1997-1998 and 2002-2003.

What I want to show in this paper is instead of the reporter's press articles exploring Champa's 'blank-out' of the events of 1971, which might provide understanding of how memories are contained through the acts of forgetting, or what function acts of forgetting may encode, the reader is instead given a clean, gory description of sexual violation in Pakistani army camps. Champa's tears, our gripped hands, her silent gesticulation, our silence spoke louder and more poignantly than words or any detailed narrative of sexual violence of 1971. The objective thereby becomes the need to stage a vision of an authentic oppressed, violated woman. The horrifying genre adopted in the description of sexual violence precisely links Champa with 'marks' that characterise her and make her a 'case'. Champa's relentless reiteration that she wanted to go back to the village or continue working in the hospital and not go to Dhaka, and the authorities' lack of engagement with her wishes should be comprehended in the context of the hospital's lack of funds, and attempts to layoff staff and dismiss patients in order to reduce operating costs.

The double horrifying genre of sexual violence by the Pakistani army and its consequential life spent in an 'oppressive' institution precisely provides the accountability factor necessary for identifying rape as a war crime globally for Bangladesh. It also enables the location of causality of the second horrifying genre in the first along with an emphasis on her dislocation from her family i.e. since Champa was raped by the Pakistani army; she was not taken back into her family and as a result spent an oppressive life in a Mental Hospital. I am critical of this framework of understanding wartime rape as it does not show how women who faced this violence have lived with this violence in their everyday.

The critique of the process of documenting narratives of sexual violence of 1971 needs to be distinguished from the various recent, revisionist deniers of Bangladesh's anyway unacknowledged genocidal history. This critique of the politics of memory would be easily read and appropriated by these recent deniers as 'political correctness' and have recently argued that 'nothing happened in Bangladesh.' My work starts where the testimonial forms end to explore how private pain of war-time rape is made part of the public memory and adapted to human right frameworks. This does not negate the events of historical injury which itself generated these narratives within various contexts. There is no doubt that East Pakistani women were raped by the Pakistani army and their local collaborators as evidenced through the research I conducted with women who were violently raped during the war. Many other scholars within Bangladesh are also addressing this issue by focusing on the rape and killing of women and men (who are deemed to be part of the collaborator Bihari community) by the Liberation fighters which seek to rupture the nationalist narrative. Nonetheless none of these works can deny the encounters of rape among their informants and friends as evidenced through long term, detailed fieldwork.

The article, argues that in trying to accommodate personal narratives of sexual violence to the hybrid language of global accountability and national contingency of history-making, the complexity and consequences of sexual violence among women embodying the subjects of that history is lost. While it is important for the left-liberal community to aspire and aim for their ethical future, at the same time it is important that when they represent the narratives of sexual violence they should reflect first and foremost the desires and wishes of the women whose narratives are being highlighted instead of a macro, national objective. Otherwise a disjunction would arise between this macro narrative and the personal lives embodied by the narratives, which are then often reduced and compromised to conform to this macro narrative. The zeal to document untold histories should not make researchers and activists lose sight of the complexity and consequences of the war-time and post war-time encounters of women who were raped during this war. What constitutes these narratives of rape should not be deductively pre-determined and should include the various nuances of experiences as expressed by the women concerned. As a result, a dual ethical future emerges that is able to include both the micro-level nuances of personal experience and the macro-level aspirations of national memory and justice.

This is the abridged version of the main article.

Nayanika Mookherjee, Lancaster University.

Ratify ICC Statute

The Second International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice held in Dhaka, Bangladesh on 30 and 31 July, 2009 notes the historical fact that the newly liberated Bangladesh in 1974 took a significant step by organizing international seminar on the issue of the establishment of International Criminal Court and subsequently became one of the early Asian countries to sign the Statute of Rome to establish the International Criminal Court. Bangladesh, one of the worst victims of Genocide in the 20th century, has enacted in 1973 'International Crimes (Tribunal) Act' to establish truth and justice and has amended the law in 2009 to initiate the trial process of the perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. At this important juncture in the history of Bangladesh it is expected that Bangladesh will take necessary measures to complete the process of ratification of the ICC Statute and fulfill the formalities of the UN instruments of ratification of the ICC. This would manifest Bangladesh's commitment to the development of international criminal law and attract the attention of international community.

The Second International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice held in Dhaka, Bangladesh on 30 and 31 July, 2009 notes the historical fact that the newly liberated Bangladesh in 1974 took a significant step by organizing international seminar on the issue of the establishment of International Criminal Court and subsequently became one of the early Asian countries to sign the Statute of Rome to establish the International Criminal Court. Bangladesh, one of the worst victims of Genocide in the 20th century, has enacted in 1973 'International Crimes (Tribunal) Act' to establish truth and justice and has amended the law in 2009 to initiate the trial process of the perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. At this important juncture in the history of Bangladesh it is expected that Bangladesh will take necessary measures to complete the process of ratification of the ICC Statute and fulfill the formalities of the UN instruments of ratification of the ICC. This would manifest Bangladesh's commitment to the development of international criminal law and attract the attention of international community.

Conference details available online

The two day Second International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice was available via streaming media online for participants to from various countries to watch the proceedings live right from their home or office. More than 500 viewers from across the globe attended this conference with the help of the internet. Drik and Telnet were the technology partners for this event. Shumon J. of New York noted "Broadcasting online has really helped the Bangladeshi expatriates to participate in such an important event."

Video report of the conference will be available online shortly at the Liberation War Museum's website. For papers presented and more, please visit this conference's website at http://www.liberationwarmuseum.org/genocide/

International law and peacemaking

Helmut Scholz

Bangladesh has changed quite drastically in the past year. I hope that while I am here I can experience the results of many of these changes, and what they mean to you, firsthand. The elections have revived significant debates about the history, identity and the future of Bangladesh. A new window is open for social reconciliation and for the legal prosecution and conviction of the crimes of 1971. The chances have grown that the “International Crime Tribunal Act of 1973" can resume its work. The hopes of the people lie with the support of the UN and the EU as they undertake this process. With the 2nd Genocide Conference, they deliberately place their historical recovery in an international context.

A new chapter in the history of international law began in 1998, with the Rome Statute and the creation of the ICC. Ironically, even though the USA played a crucial role in the Nuremberg trials, it has rejected the International Criminal Court even to this day. The International Criminal Court -independent of historical events - cannot indict any crimes against humanity that happened before 2002. Yet its establishment, its statute, brought one decisive, crucial question back into play. It is - in my opinion - the question of the ICC's peacemaking role in bringing about the nonviolent organization of societies after violent conflict, even after genocide. Thus the history of the ICC is also of enormous importance for the creation of a legal environment in which we can prosecute past crimes against humanity.

I shall now describe the three key factors that would produce an environment where the peacemaking function of modern international law is realistic.

The first key factor is: the social and legal processing of war crimes and crimes against humanity will continue to be effective if and only if a high degree of transparency and accessibility to information for the general public is guaranteed. Investigative work, research and investigative journalism must be given broad entitlement to create an educational climate in public debates.

As for the second factor, the necessity of international legal punishment for crimes against humanity can be only one part of a comprehensive historical analysis and cultural debate. The peacekeeping role of international law will only be successful if the legal processes are supported by society and protected against false judgments, such as being cast aside as worthless debates or being used to justify historical amnesia as a more preferable alternative. Reconciliation is more than just necessary legal confrontation. Reconciliation must create a climate of dialogue and understanding, a climate that produces cross-generational interest, so that the complex motives and societal causes of violence and crime can be processed. This does not mean avoiding uncomfortable questions - on the contrary, in some sense a public debate would not create a legal, but instead, a cultural climate of absolution, in which the chance exists for the historical understanding of both perpetrators and victims to grow. As long as the complex social causes and consequences of conflict remain in the dark, legal actions which attempt only to cast blame on individuals is pointless. Without corresponding support and change from society itself, punishment and atonement only continue the cycle of revenge and the martyr mentality that allows concepts of justice to be ideologically abused.

No case of reconciliation can be relativized, but instead must always serve as part of the struggle to understand how to violence, war and crime happen in the first place. Only with a mentality open to learning lessons from the past can the lessons for future generations be formed and kept in remembrance.

Thus not only the legal but also the historical and social analysis of crimes against humanity must be protected from political exploitation - which is the third factor. This means that procedures must be installed which guarantee an independent exercise of international criminal processes. In this respect, the admission procedure mechanism, as stated in article 13 of the Rome Statute for the Prosecutors of the ICC, constitutes an important step for the independence of future international tribunals. The so-called trigger mechanism for the beginning of a procedure provides three independent means by which proceedings can be accepted and commenced: a referral by the Contracting States, a referral by the UN Security Council, and an authorization by the prosecutor - on the basis of "contextually prevailing evidence" and then only with oversight by a Pre-Trial Chamber ex officio. This law served in the ad hoc -criminal courts from Nuremberg, Tokyo, Yugoslavia and Rwanda as a basic defense mechanism against political exploitation by the UN Security Council or the Assembly of Charter States, meeting a new standard of independence and universality in international law jurisdiction.

To create a law of the 21st Century, an international law that would serve to secure the equitable and peaceful coexistence of all nations - I would like to briefly summarize what we have discussed so far- we must guarantee or strive for,

i. extensive requirements for transparency and education,

ii. equal and concurrent legal and social analysis and

iii. protection against political exploitation.

The question now remains whether we can actually achieve a universal, independent, and neutral law in international relations, a law with a claim of securing peace, a law with respect for the teachings of the 2nd World War in the 21st Century. I think the steps taken by the Rome Statute and the ICC have been very important. They do not, however, replace a social debate, a difficult cultural confrontation, in each case, the processing of international law violations and crimes against humanity.

In my opinion, Bangladesh now has a similar task before it in handling the crimes of 1971. Each path open to reconciliation is a gift for the whole international community, for democracy and peace on our common globe. For the crimes in Bangladesh, a legal analysis similar to the Cambodian model, combined with international support, is highly recommended. What is important is the accompanying debate in society, keeping in mind the scale of their responsibilities toward future generations. Here, in addition the demand for legal reparations, the question of the origins of violence and reconciliation must also be allowed to be openly debated. Politics of history is a task for civil society. Violence must be banished by getting rid of its causes. This cannot simply be ordered by the state, but only comes through discussion and learning to organise.

Helmut Scholz, Member, EU Parliament.