Life after a fire

Sitting on a bench on the premises of Bangabandhu Bidyaniketon, 50-year-old Majeda Begum was crying. She wasn't the only one. Around her were other tenants of Jhilpar slum, which caught on fire on the 16th this month and gutted around 2,500 shanties in Rupnagar, Mirpur. Majeda was sobbing because the school authorities had just ordered them to leave the classrooms. They could no longer accommodate them, the authorities said, as students had to sit for the exams Saturday onward (August 24). She feared that if the school didn't allow them to stay on at the compound, she had no other place to reside in the city, save for the last resort of the homeless—the footbridge or footpaths.

Due to the fire, Majeda lost all her possessions for the second time in her life. After getting married at the age of 13, she and her husband had to move to Dhaka after losing their cultivable lands, domestic animals and their home in Bhola, Barisal in a flood. Upon coming to Dhaka, like many other climate refugees, they took shelter in a makeshift house in Jhilpar slum.

"We were here from the very beginning of this slum. We even bought two rooms from the then-house owners. They now have a high-rise building near the road, but my luck didn't favour me. First, we were evicted from our roadside house, and our home was demolished to build a 14-storey shopping mall. After losing our home, we started to rent again. But this fire has made us complete beggars," she said.

"My two sons used to work at vegetable shops at the nearby bazaar. We lost our television and refrigerator which was bought with their hard-earned money. Besides, there was around Tk 20,000 in cash, some gold jewelry, an almirah, and other belongings. We could not save anything but our lives."

Shantona Begum was seen piling up the burnt tin and bricks of her rented house, but she didn't know what to do with these scraps of her former life. She used to rent the room for Tk 1,500. She has already looked for rented rooms in the Rupnagar area but has so far failed to find a room for less than Tk 5,000. As a domestic worker, she doesn't earn more than Tk 6,000 a month. "I have nobody in this city. My husband married another woman. After the fire, he has stopped visiting me. I really don't know where I will go with my daughter. I came to this city empty-handed; I will leave empty-handed. I couldn't save anything," she says.

People like Majeda and Shantona are the most helpless victims of fires which routinely wipe out informal settlements in the city. While those who own rooms in the slum have started rebuilding makeshift structure using tarpaulin and bamboo poles, tenants (like these two women) have no such scope.

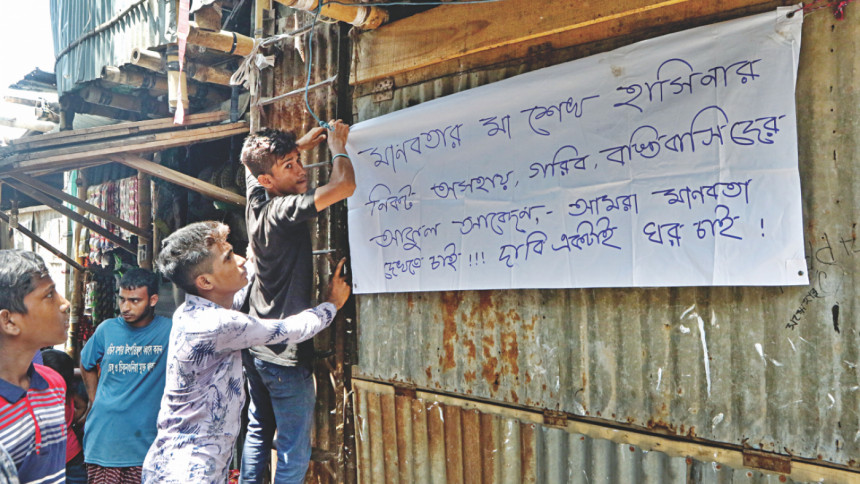

Although Awami League General Secretary Obaidul Quader and Dhaka North City Corporation (DNCC) officials declared that the government will provide full support along with relief materials until the affected are completely rehabilitated, the residents say they are not getting any support other than food. In fact, many complain that newer tenants (who had only been renting for less than four to five months) are not even getting food, because the slum leaders who are providing food do not recognise them.

"They are even skipping our names in the list of affected people as they don't know our faces. At this time, we have no other way to survive," says Rahim, a rickshaw puller who has only been living at the Jhilpar slum for the last four months.

With no other option, a large number of tenants of Jhilpar slum have already taken shelter with relatives or left for their village homes. Those who have no such support have scattered to other informal settlements in the city or are living on the streets.

According to the Census of Slum Areas and Floating Population 2014, administered by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), around 2.23 million people live in informal settlements, 60 percent higher than the last census (1.39 million) in 1997. Although article 15 (a) of the constitution states that it shall be a fundamental responsibility of the state to provide basic necessities of life, including food, clothing, shelter, education and medical care, these provisions are rarely used in the case of millions of urban migrants who live in informal settlements.

After many such fires, although both government and non-government organisations promise to rehabilitate those affected, in reality, these are nothing but broken promises, say the residents. Salema Khatun has had her home burnt down in two fires in two years. She migrated to 'Jahangirer Bosti' at Bhashantek area of Mirpur after the Ilias Mollah slum at Mirpur 12 caught fire last year. Although she was promised a shelter in the aftermath of the fire, she ultimately had to give up hope as her house owner was facing hardships in rebuilding. Later, in February this year, her house in Bhashantek slum was burnt in a massive fire. Now she is living in her daughter's house at Kazipara, Mirpur.

"We both work in people's houses as domestic help. It is very difficult for my family of six to live in one room, but I don't have any option as I cannot rent more space with our small income," says Rabeya Begum, Salema's daughter.

The Korail slum fire that gutted at least 500 houses and left nearly 4,000 families homeless in 2017 also showed that tenants in informal settlements are forced to migrate after the fire. In accordance with the decision of DNCC and BRAC's urban development programme, owners were provided with housing materials such as tin and bamboo poles to rebuild. "We had instructed the house owners to excuse rent for the first few months so that the tenants can also stay there. This way we were able to lessen the number of migration, because everyone was eager to rehabilitated," says Chowdhury Md Fahim Ragib, senior regional coordinator of BRAC's Dhaka urban development programme.

But the migration rate goes up when the government remains unwilling to initiate housing in particular slums, which leave thousands of house owners homeless. They had once bought these rooms for around Tk 30,000 to Tk 90,000, depending on the location and size of the rooms. In such cases, both tenants and owners allege that fires set in informal settlements are nothing but an act of sabotage to evict them. Their claims are not out of the blue—informal settlements in the city have time and time again been 'developed' to be replaced with high-rise buildings, by either the government or real estate companies after a fire or forced eviction. For poor tenants and owners of rooms in these areas, there is no change in this never-ending cycle of migrating around the city in search of a place to live.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments