Into the world of cryptology and intelligence

At the outbreak of the war, many nations had weak or fledgling national intelligence communities. The French government and military both maintained trained intelligence forces, but no central agency processed intelligence information, or facilitated the distribution of critical intelligence information. Russia had special agents of the Czar, and secret police forces, but its foreign intelligence infrastructure was almost non-existent.

The US developed stronger domestic intelligence and investigative services in the decade before World War I. However, the country's lingering isolationism and neutral posture in the war hampered the development of a foreign intelligence corps until the US entered the war in 1917.

Britain had a well-developed military intelligence system, coordinated through the Office of Military Intelligence. British intelligence forces engaged in a range of specialised intelligence activities, from wiretapping to human espionage. The vast expanse of British colonial holdings across the globe provided numerous outposts for intelligence operations, and facilitated espionage. British forces were among the first to employ a unit of agents devoted to the practice of industrial espionage, conducting wartime surveillance of German weapons manufacturing.

Of all the warring nations in 1914, Germany possessed the most developed, sophisticated, and extensive intelligence community. The civilian German intelligence service, the Abwehr, employed a comprehensive network of spies and informants across Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and in the United States. German intelligence successfully employed wire taps, infiltrating many foreign government offices before the outbreak of the war.

World War I forced most national intelligence services to rapidly modernise, revising espionage and intelligence tradecraft to fit changing battlefield tactics and technological advances.

COMMUNICATIONS AND CRYPTOLOGY

Advancements in communications and transportation necessitated the development of new means of protecting messages from falling into enemy hands. Though an ancient art, cryptology evolved to fit modern communication needs during World War I. The telegraph aided long-distance communication between command and the battlefront, but lines were vulnerable to enemy tapping. All parties in the conflict relied heavily on codes to protect sensitive information. Cryptology, the science of codes, advanced considerably during the first year of the war. Complex mathematical codes took the place of any older, simple replacement and substitution codes. Breaking the new codes required the employment of cryptology experts trained in mathematics, logic, or modern languages. As the operation of codes became more involved, the necessity for centralized cryptanalysis bureaus became evident. These bureaus employed code breakers, translators, counterintelligence personnel, and agents of espionage.

The most common codes used during the war continued to be substitution codes. However, most important messages were encrypted. Encryption further disguised messages by applying a second, mathematical code to the encoded message.

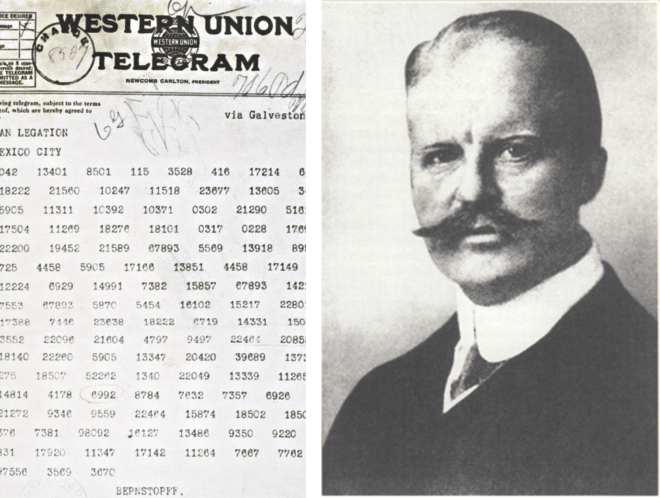

Both the Germans and the British broke each other's World War I codes with varying success. The German Abwehr broke several British diplomatic and Naval codes, permitting German U-boats to track and sink ships containing munitions. British cryptanalysis forces at Room 40, the military intelligence code-breaking bureau, successfully deciphered numerous German codes, thanks in large part to the capture of German codebooks. In 1917, British intelligence intercepted a diplomatic message between Berlin and Mexico City, relayed through Washington. The message, known as the Zimmermann Telegram, noted German plans to conduct unrestricted warfare against American ships in the Atlantic, and offered to return parts of Texas and California to Mexico in exchange for their assistance. Discovery of the Zimmermann Telegram prompted the US to enter World War I.

Cryptology, once the exclusive tool of diplomats and military leaders, became the responsibility of the modern intelligence community. After World War I, many nations dissolved their wartime intelligence services, but kept their cryptanalysis bureaus, a nod to the growing importance of communications intelligence and espionage.

Source: www.faqs.org

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments