Development is all about enlarging freedoms for all so that every human being can pursue the choices they value and raise their voices in support of those choices. One such freedom is, of course, well-being freedom. The other is agency freedom, represented by voice and autonomy. Agency is related to what a person is free to do and achieve in pursuit of whatever goals or values they regard as important. Women in Bangladesh are deprived of both freedoms. Over time, although women have progressed in terms of well-being freedom, they remain severely deprived and discriminated against in the arena of agency freedom. Part of this has to do with patriarchy, social structures, norms and values, but a significant part relates to public policies.

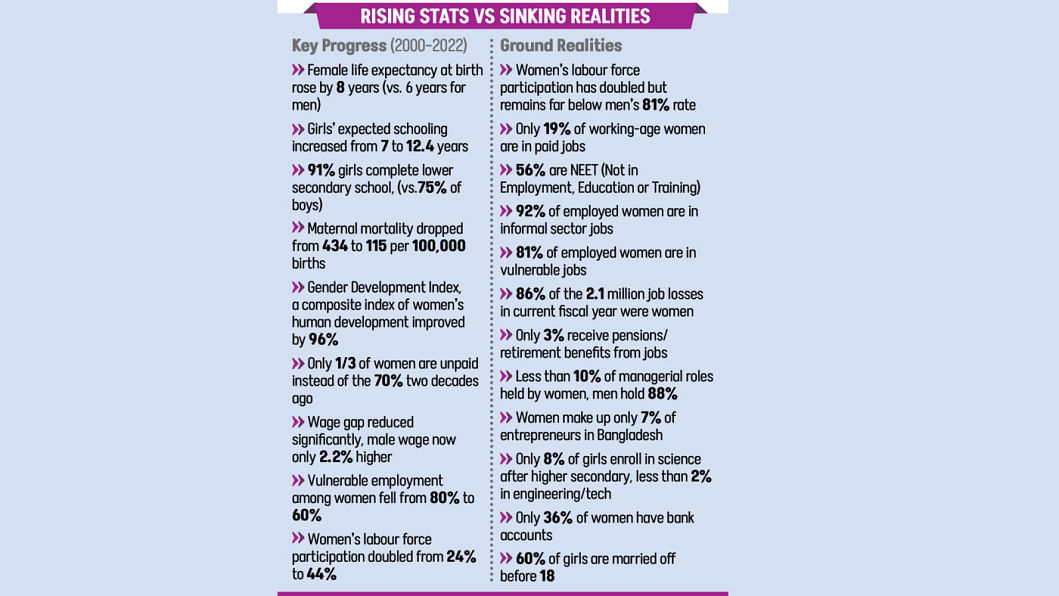

The labour force participation of women is often treated as a proxy indicator of women's economic empowerment. The labour force participation rate of women in Bangladesh has steadily increased from 24 per cent in 2000 to 44 per cent in 2022. However, it remains much lower than the male labour force participation rate of 81 per cent. Only one-third of women are unpaid now, compared to 70 per cent two decades ago. The wage gap between women and men has been significantly reduced in recent years — the male wage is now only 2.2 per cent higher than that of women. Vulnerable employment among women has declined from 80 per cent in 2000 to 60 per cent in 2022.

Despite the country's significant progress and the strides Bangladeshi women have made over the years in many areas of life, considerable disempowerment and structural and social barriers remain in terms of their well-being, voices and choices. Women in Bangladesh are still disempowered on many fronts — economic, political, social and cultural. Several factors are responsible for this disempowerment. Economic factors include financial dependency on men, limited ownership of land, and restricted employment opportunities. Socio-cultural and religious factors encompass areas such as illiteracy, culturally neglected social apathy, intra-household discrimination, and seclusion. Political factors include indifference from political parties and limited participation in electoral politics.

Economic empowerment of women is critical to their well-being, voice and choice. In Bangladesh, only 19 per cent of working-age women (aged 15–65) are in active employment and earning, while 56 per cent are not in employment, education or training (NEET). Fewer than 10 per cent of Bangladeshi women hold managerial positions, while the corresponding figure for men is 88 per cent. Furthermore, about 92 per cent of employed women work in the informal sector, characterised by high gender wage gaps and lack of benefits. Although the rate of female entrepreneurship is growing, women constitute only 7 per cent of the 7 million entrepreneurs in the country, and the number of women-led businesses remains small. Only 15 per cent of Bangladeshi firms have female owners or co-owners. Women are concentrated in low-paying, low-productivity agricultural activities and unpaid work, which may adversely affect their economic decision-making ability. Around 30 per cent of employed women are engaged in unpaid work. With regard to unpaid domestic and care work, women spend 25.8 per cent of their time on such tasks, while men spend just 5 per cent.

The situation regarding female joblessness in Bangladesh is quite severe. Even though official figures put the female labour force participation rate at 41 per cent, in reality it has been found to be around 19 per cent. This means that only 19 out of every 100 women attempt to engage in economic activities — and not all of them secure jobs. The actual unemployment rate for women in Bangladesh has been found to be nearly 10 per cent, far higher than the official figure of 4 per cent. Among young women, the unemployment rate exceeds 22 per cent. It goes without saying that, due to the way unemployment is defined and calculated, official figures significantly underestimate the real situation on the ground. Thus, the actual joblessness of women in the Bangladeshi economy is much higher than officially acknowledged. Overseas employment for Bangladeshi women has also significantly declined — from over 8,000 in 2022 to fewer than 5,000 so far this year.

Furthermore, female employment in Bangladesh is mostly in vulnerable jobs, characterised by low productivity and poor returns. In the first half of the current fiscal year, 2.1 million jobs were lost — and women accounted for about 86 per cent of that loss. Women hold only 3 per cent of industrial jobs. Of the women in employment, 81 per cent are in vulnerable positions. Thus, employment conditions for women remain fragile. Only 3 per cent of employed women receive pensions or retirement benefits through their employers.

In Bangladesh, women's joblessness is due to many factors — some economic, some social, and some cultural. For example, social and cultural norms dictate that women should work within the household. Therefore, it is no wonder that in agriculture, 80 per cent of the post-harvest work is done by women. Furthermore, as land ownership is biased against women, they are not engaged in direct crop-growing activities either as owner-cultivators or sharecroppers. Because of the traditional notion that women should work within households, they are also more engaged in cottage industries. Due to socio-cultural norms, women have been pushed into all sorts of unpaid care work within the household. These forms of work are not valued in the national income accounts. Thus, women bear a disproportionate burden of unpaid care work, limiting their opportunities for paid employment. Women also engage in self-employment, but they are mostly occupied in low-productivity and poorly paid informal sectors. These activities are also vulnerable to shocks. As a result, women bear a disproportionate burden when the labour market experiences economic, financial shocks and other kinds of disasters.

Women are also disadvantaged in the job market because of their limited access to information and communication technology (ICT). In Bangladesh, while 86 per cent of males own mobile phones, the corresponding number for women is 61 per cent. Only 16 per cent of females use mobile internet, which is less than half the rate of men at 33 per cent. Women face challenges in accessing high-quality ICT services due to a lack of awareness about the benefits of ICT for women, cultural norms, and beliefs that internet access for women is not good for society. In terms of building women's capabilities for better jobs, while Bangladesh boasts of more girls passing secondary and higher secondary studies, only 8 per cent of them enrol in science departments, with fewer than 2 per cent in engineering and technology. Therefore, women in general are not part of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) education. Yet these are the skills needed in the current and future world of work.

Several factors are critical to women's economic empowerment. There are direct factors such as education, skills development and training, access to quality, decent and paid work, addressing unpaid care and work burdens, access to property, assets and financial services, collective action and leadership, and social protection. There are also underlying factors such as labour market characteristics, fiscal policy, legal, regulatory and policy frameworks, gender norms, and discriminatory social norms. Women also lack control over their income. Their access to assets is constrained. Women in Bangladesh have less access to finance, as men often do not allow them to have financial independence. Furthermore, for self-employed women, one major constraint is access to credit. The formal banking system is not keen to provide credit because women's creditworthiness is undervalued. Only 36 per cent of Bangladeshi women have bank accounts.

Early marriage continues to be an impediment to women's socio-economic empowerment. Currently, almost 60 per cent of adolescent girls are married before the legal age of 18. Early marriage limits the capabilities and reduces the opportunities of Bangladeshi women. Marriage is also the most common reason why girls drop out of school. The lack of human security for women is a major dimension of social disempowerment in Bangladesh. Domestic violence is a serious threat to them. The rates of violence against women remain high. In 2016, in Bangladesh, one in every two married women and girls reported having endured domestic violence during their lifetime. Sexual harassment, acid attacks, and suicide are also issues related to their safety and security. Child marriage is closely correlated with high adolescent pregnancy. Girls under the age of 18 have little control over their reproductive health and little autonomy over their reproductive decisions. In fact, in Bangladesh, 53 per cent of adolescent girls do not have control over their reproductive health. One in every four married girls below 18 becomes pregnant. Last year, 28 per cent of adolescent girls between the ages of 15–19 were victims of physical or sexual violence by their partners.

Violence against adolescents, both boys and girls, is a pertinent social issue for Bangladesh. Adolescent girls, regardless of their marital status, continue to be vulnerable to all forms of violence. The hidden battle faced by victims of domestic violence is within the household — they are isolated, without support or resources, suffering in silence, fearing further abuse or retribution, and burdened by shame and stigma, which further inhibit them from seeking assistance or reporting abuses.

The extreme form of animosity and prejudice against women is reflected in various forms of violence committed against them — within households, in workplaces, and on the streets. That violence is on the rise in society, and women are being increasingly attacked in different spheres of life. In some cases, this takes the form of bodily harm and mental torture; in others, it manifests as sexual harassment and rape; and in yet others, through direct physical attacks. During the first two months of this year, about 400 women and girls were reported to have been victims of violence. There were also 48 cases of rape. It goes without saying that these figures are underestimates of what actually occurred on the ground.

In fact, the current level of animosity and violence against women has become a frightful situation. Such violence is no longer an exception but has become a norm. The state and society must take responsibility for it — and so must men — because many of the lived realities of women are determined by the actions of men. The challenge that has recently been raised against gender equality is a prejudice against equality, an animosity against humanity, and a threat to us all.

Patriarchy remains the major driver of the social disempowerment of Bangladeshi women. It essentially controls their lives and aspirations, and sets parameters for what they can do and become. Patriarchy has both economic and political implications, which manifest in different ways. The majority of Bangladeshi women — regardless of where they live or what their employment status is — report handing over most of their earnings to their husbands or other family members.

Patriarchy also often denies women their voice or political agency. Women are not traditionally expected to have active interest in politics, to participate in political movements, or to hold political views, ideas or preferences. They are not expected — particularly in rural areas — to have a voice or autonomy in choosing candidates or voting during elections. Men often make such political decisions on their behalf.

In short, the space for women to enjoy their well-being, choice, voice, and autonomy is limited. This is particularly unfortunate, as women participated side by side with men in the Liberation War of Bangladesh. Having their say is essential for both the well-being and agency freedom of Bangladeshi women.

Selim Jahan is former Director of the Human Development Report Office under the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and lead author of the Human Development Report.

Comments