Law Alter Views

Land

Righs of the Indigenous Peoples

Kawser

Ahmed

This

article is written as a sequel to my earlier article entitled

"Between Empire and Nationalism: The marginalisation

of the indigenous people in Bangladesh" published

in Law and our rights page wherein I have tried to demonstrate

that changing dimension of mainstream politics, i.e. from

a secularist tradition to reintroduction of Islam based

nationalism, is one of the prominent reasons for marginalisation

of the indigenous peoples in Bangladesh. In that article

I have also maintained that the political trend in Bangladesh

should be set in a secular way in order that a wholesome

congenial political and social atmosphere may come along

for the protection and promotion of the rights of the

indigenous peoples. Along with this, I have advisedly

made an observation that there are some problems pertaining

to the indigenous peoples which are not soluble except

for some legal mechanism. The problem relating to land

rights of the indigenous peoples is of such nature.

Presently,

the rubric concerning the idea of land rights of the indigenous

peoples owes directly to international law. In international

law, a number of recent prescripts like the Indigenous

and Tribal Peoples Convention 1989, the Indigenous and

Tribal Populations Convention 1957 and the UN Draft Declaration

on the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples have advocated

for the land rights of the indigenous peoples. Here it

begs some pertinent questions: why did international law

take so much time to recognise the rights of the indigenous

people, especially land rights; why the European and North

American states are so reluctant to sign any convention

on the rights of the indigenous peoples? The answer to

this question will take us to the heart of the matter

in question to be addressed in this article. To deal with

it very concisely from a theoretical standpoint, it is

suffice to sayhistorically the indigenous peoples are

missing factors in modern sate-making process for a variety

of reasons. Since state is the most prominent actor in

both national and international law making process and

there was lack of effective participation in the state

mechanism by the indigenous peoples, states have never

espoused indigenous cause, which has engendered their

legal deprivation in national and international law.

The

statement made above appears to be more evident in those

cases where European settlers or colonisers had occupied

and made settlement in the regions inhabited by the indigenous

peoples. Throughout the period of late middle age down

to 19th century, the eurocentricism in both legal scholarship

and military power had given European nations an unrivalled

opportunity to interpret international law from their

own respective standpoint, and in defining the legal status

of the indigenous peoples they have taken full opportunity

of it to legitimise their activities by some unjust doctrines

like terra nullius, just war or other methods like conquests,

unequal treaties etc. Though scholars like Grotius, Vittoria,

Pufendorf and vattel considered them to be "political

entities with territorial rights, we see that this status

was played down later during the nineteenth century. In

early decades of the twentieth century, the indigenous

peoples were thrown outside the purview of international

law. Such as, in the Island of Palmas case, the Permanent

Court of International Justice declared that agreements

with native princes or chiefs of indigenous peoples did

not create rights and obligations such as may, in international

law arise out of treaties. A few years later the Permanent

Court of International Justice went as far as in the Legal

Status of Eastern Greenland case, 1933 that the indigenous

peoples of Greenland could not acquire sovereignty by

conquest.

In

the second phase, when settler communities in those colonies

became large enough to establish their own states and

did so eventually, the colonialist attitude of the ruling

class to the indigenous people in the newly emergent states

did not change overnight. The establishment of modern

states by the colonialist settlers in the indigenous populated

territories paved the way for a far better legal interference

in the land rights of the indigenous peoples because it

is an axiom of modern political science that state has

sovereign power over its territory. Here we are not going

to make a critical analysis of jus imperium power of state

because it is not pertinent in the present discussion,

yet it is true that the doctrine of jus imperium has always

come handy for the ruling class to eject the indigenous

people from their land.

United

States, Canada and Australia can be regarded as very good

case in points to exemplify this situation. These countries

still assert or previously asserted jus imperium power

to "extinguish" the land titles and rights of

the indigenous peoples within their borders, without the

consent of the indigenous peoples by means of enactments

or judicial and administrative orders. The process of

'extinguishment' includes voluntary purchase and sale

of title, outright taking or expropriation, without just

compensation. One clear example of the problem of extinguishment

is manifested in the case of the Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v.

United States, 348 U.S. 272 (1995). "In this case

the Supreme Court decided that the United States may (with

limited exceptions) take or confiscate the land or property

of an Indian tribe without due process of law and without

paying just compensation, this despite the fact that the

United States Constitution explicitly provides that the

Government may not take property without due process of

law and just compensation. The Supreme Court found that

property held by aboriginal title, as most Indian land

is, is not entitled to the constitutional protection that

is accorded all other property". [UN Doc. E/CN.4/Sub.2/2001/21].

In the final working paper on the Prevention of Discrimination

and Protection of Indigenous Peoples and Minorities, the

special rapporteur Mrs. Erica-Irene A. Daes has noted

about it as follows:

United

States, Canada and Australia can be regarded as very good

case in points to exemplify this situation. These countries

still assert or previously asserted jus imperium power

to "extinguish" the land titles and rights of

the indigenous peoples within their borders, without the

consent of the indigenous peoples by means of enactments

or judicial and administrative orders. The process of

'extinguishment' includes voluntary purchase and sale

of title, outright taking or expropriation, without just

compensation. One clear example of the problem of extinguishment

is manifested in the case of the Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v.

United States, 348 U.S. 272 (1995). "In this case

the Supreme Court decided that the United States may (with

limited exceptions) take or confiscate the land or property

of an Indian tribe without due process of law and without

paying just compensation, this despite the fact that the

United States Constitution explicitly provides that the

Government may not take property without due process of

law and just compensation. The Supreme Court found that

property held by aboriginal title, as most Indian land

is, is not entitled to the constitutional protection that

is accorded all other property". [UN Doc. E/CN.4/Sub.2/2001/21].

In the final working paper on the Prevention of Discrimination

and Protection of Indigenous Peoples and Minorities, the

special rapporteur Mrs. Erica-Irene A. Daes has noted

about it as follows:

"The

legal doctrine created by this case continues to be the

governing law on this matter in the United States today.

The racially discriminatory character of the decision

has not prevented this doctrine from being freely used

by the courts and by the United States Congress in legislation,

even in recent years. Indeed the Congress relied on this

doctrine in 1971 when it extinguished all the land rights

and claims of practically every one of the 226 indigenous

nations and tribes in Alaska by adopting the Alaska Native

Claims Settlement Act." [ UN Doc. E/CN.4/Sub.2/2001/21].

Another

clear example is Mabo v. Queensland, 1992 wherein

the High Court of Australia ruled that though the doctrine

of terra nullius is not applicable to deny rights of the

indigenous peoples to land, the Crown is vested with sovereign

power of to extinguish native title. Nonetheless the Court

held that native title may be extinguished by legislation,

by alienation of land by the Crown or by appropriation

of land by the Crown in a manner inconsistent with the

continuation of native title. The Native Title Amendment

Act, 1998 has provided a number of means by which indigenous

title can be extinguished and preference of rights of

non-native title holders over those of native title holders.

The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

has found various provisions of the Act discriminatory

[Decision (2) 54 on Australia, 18 March 1999 (A/54/18,

Para. 21)].

The

position of Canadian law seems less harsh in regard to

indigenous people's right to land. Although the Constitution

Act of 1982 does not allow government to "extinguish"

aboriginal rights over land, it may be encroached on by

the "justified" needs of the larger society.

Chief Justice Lamer of the Supreme Court of Canada in

a case has mentioned some grounds on which he has held

infringement on aboriginal title is justified. Needless

to say, the grounds are not at all commensurate with values

and purpose of indigenous peoples. [Delgamuukw vs.

The Queen, paragraph 165 of the Chief Justice's opinion,

unpublished decision, 11 December 1997. Also see UN Doc.

E/CN.4/Sub.2/2001/21].

Now

let us turn our attention to situation prevailing in Bangladesh.

Shortly speaking, the traditional land rights of the indigenous

peoples came under attack by British colonisation and

subsequent implementation of imperial laws regarding land

and revenue management. The general landlord-tenant relationship

created by the British law did not feature any special

indigenous rights as such. In 1950, the State Acquisition

and Tenancy Act also did not recognise any special rights

of the indigenous peoples attached to land. However the

legal regime regarding indigenous people based on land

entitlement is clearly divisible into two categories:

1. legal regime created under CHT Peace Accord signed

on December 2, 1997 between the National Committee on

Chittagong Hill Tracts and the Parbattya Chattagram Janasanghati

Samity, and 2. legal regime in which the State Acquisition

and Tenancy Act 1950 and other laws are applicable.

An

important feature of the CHT Peace Accord is that by virtue

of section 26 of part "B" management of land

excluding reserved forest, Kaptai Hydroelectricity Project

area, Betbunia Satellite Station area, state-owned industrial

enterprises and lands recorded in the name of the government

has been vested in the Parbatya Zilla Parishad. Furthermore

the government has been debarred from right to acquire

or transfer any lands, hills and forests under the jurisdictions

of the Hill District Parishad without prior discussion

and approval of the Parishad. Yet the Peace Accord has

some weakness like non-recognition by the Constitution,

or delay in establishing land-commission etc.

Elsewhere

in the country other than CHT, the indigenous peoples

do not have as much rights as is guaranteed under the

CHT Peace Accord. In those places their land tenures are

regulated by general laws which have shoved them to a

greater magnitude of vulnerability. Because, alongside

state's intervention, there are threats of eviction from

land grabbers, influential figures and tea-estates. So

what should be done right now is to chart out the areas

heavily inhabited by the indigenous peoples, and give

confirmation of their land rights by making special laws.

Otherwise we are going to exterminate the descendants

of the first human beings on earth.

The

author has graduated from Department of Law, University

of Dhaka.

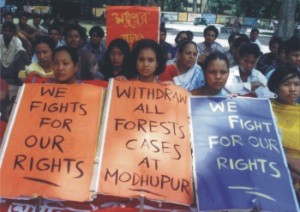

Photo:

Star