Law opinion

Making the law work for everyone

An innovative perspective on the legal empowerment of the poor

A.H. Monjurul Kabir

The UN sponsored Commission on the Legal Empowerment of the Poor in its global report -'Making the Law work for Everyone (hereinafter legal empowerment report)'raised several critical issues including some alarming information: Two in every three people on the worldsome 4 billion in totalare “excluded from the rule of law.” In many cases, this begins with the lack of official recognition of their birth: around 40% of the developing world's five-year-old children are not registered as even existing. In most cases protection of legally enforceable property rights are absent.

The UN sponsored Commission on the Legal Empowerment of the Poor in its global report -'Making the Law work for Everyone (hereinafter legal empowerment report)'raised several critical issues including some alarming information: Two in every three people on the worldsome 4 billion in totalare “excluded from the rule of law.” In many cases, this begins with the lack of official recognition of their birth: around 40% of the developing world's five-year-old children are not registered as even existing. In most cases protection of legally enforceable property rights are absent.

After listening to commission co-chairs Madeleine Albright and Hernando de Soto on June 3rd at the United Nations in New York during the first official launch of the report, I do agree that the inextricable link between pervasive poverty and the absence of legal protections for the poor has been overlooked in the policy discourse for too long. For Naresh Singh, Executive Director of the Commission, the main challenge is how to get the excluded to become shareholders in the economy and thereby reduce the inequity gap. As food crisis grows, report finds four billion people are excluded from the rule of law Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor makes a global call to make legal empowerment a key pillar of the anti-poverty agenda

Of course, there might be dissenting views on some of the assertions made in the report i.e., whether there could be legally binding business rights, whether the total number of people without protection of law could be effectively measured (including the total number of people without ant protection of law) etc. However, nobody denies the critical need of the legal empowerment in promoting an inclusive development agenda. Full recognition of legal identity, assured access to the courts, basic labour protection, the right to own property and the rule of law to prevent exploitation by the powerful are vital tools to enable the poor to realise their full potential.

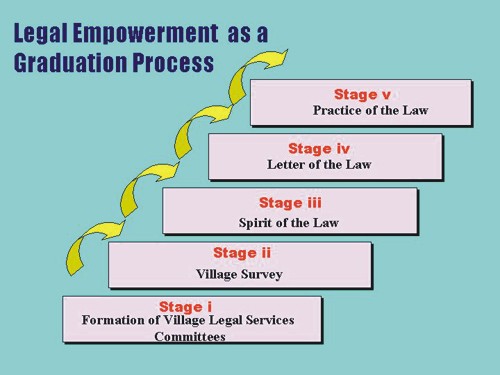

Participative, transparent and responsive governance

In the absence of adequate framework of legal empowerment and protection both at national and sub-national levels, chances are high that existing participative processes and monitoring may not be successful to influence sustainable pro poor policy and reduce inequities. As reiterated in the legal empowerment report, there are no technical fixes for development. For states to guarantee their citizens' right to protection, systems can and have to be changed, and changed systemically. Legal empowerment is one of the central forces in such a reform process. It involves states delivering on their duty to respect, protect and fulfil human rights and the poor realising more and more of their rights, and reaping the opportunities that flow from them, through their own efforts as well as through those of their supporters, wider networks and governments. However, the legal empowerment report does not suggest how to measure the progress towards legal empowerment. Therefore, any initiative to strengthen such framework and legal protection will vary considerably.

Implementing economic, social and cultural rights

The record of national courts and National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs), although not very encouraging, are not short of innovation and potential. Take the example of the Mid-day Meal Scheme in India which involves provision of lunch free of cost to school-children on all working days. The scheme has a long history especially in Tamil Nadu and Gujarat, and has been expanded to all parts of India after a landmark direction by the Supreme Court of India on November 28, 2001. The success of this scheme is illustrated by the tremendous increase in the school participation and completion rates in the state of Tamilnadu. 12 crore (120 million) children are so far covered under the Mid-day Meal Scheme, which is the largest school lunch programme in the world. Allocation for this programme has been enhanced from Rs 3010 crore to Rs 4813 crore (Rs 48 billion, $1.2 billion) in 2006-2007.

The right to adequate housing in the context of forced evictions of slums was claimed in the Supreme Court of Bangladesh (1999) without much success. However, the court granted relief on separate ground. Young lawyers and activists are trying to use law, often innovatively (i.e., applying public interest litigation, encouraging judges to invoke judicial activism, etc.), to promote economic and social rights agenda. In fact, the MDG agenda are broader part of economic, social, and cultural rights movement, and, it is important to establish stronger linkages between the two initiatives. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) and Commission on Human Rights' Special Rapporteurs on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights endorse that human rights, including economic, social and cultural rights help to realise any strategy to meet the MDGs for example by:

* providing a compelling normative framework, underpinned by universally recognised human values and reinforced by legal obligations, for the formulation of national and international development policies towards achieving the MDGs;

* raising the level of empowerment and participation of individuals;

* affirming the accountability of various stakeholders, including international organisations and NGOs, donors and transnational corporations, vis-à-vis people affected by problems related to poverty, hunger, education, gender inequality, health, housing and safe drinking water; and

* reinforcing the twin principles of global equity and shared responsibility which are the very foundation for the Millennium Declaration.

(Source: A Joint Statement by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the UN Commission on Human Rights' Special Rapporteurs on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 29 November 2002).

The elements of Legal Empowerment are all grounded in the spirit and letter of international human rights law, and particularly in Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which declares: --All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. In fact, the first two above-mentioned examples also point to the same direction.

However, all these require a well-capacitated and functioning judicial system. Even in the rare cases when the poor can afford to go to court, the service is meager. India, for example, has only 11 judges for every 1 million people.

Rise of Informal economy

According to the Commission, report the informal economy is growing dramatically in poor countries. Over 70% of workers in developing countries have livelihoods that are not subject to public control. Even larger numbers live in isolated rural areas with limited secure access to land and other resources. They operate outside the law by entering into informal labour contracts, running unregistered businesses, and often occupy land to which they have no formal rights. In the Philippines, 65 percent of homes and businesses are unregistered, in Tanzania 90 percent. In many countries the figure is over 80 percent. The informal economy accounts for over a third of the developing world's economy.

These pose real challenge for the development community to broaden the coverage of legal protection and ensuring an enabling environment for inclusive growth. The report found that no modern market economy can function without law and power can only be legitimised by submitting to the law. It identifies four crucial pillars which must be central in national and international efforts aimed at the legal empowerment of the poor: access to justice and rule of law, property rights, labour rights, and 'business rights'.

Political process, social movements and the MDGs

MDGs and the fight against poverty will certainly require, (a) increasing involvement by parliaments, political parties, social movements and (b) enhanced accountability that is sensitive to disadvantaged and vulnerable groups and to institutional histories of marginalisation. On all these fronts, MDG agenda could have achieved more. Recent development in East Africa, Southeast Asia, South Asia and Central America are stark reminders that our interventions require an informed, proactive, and innovative engagement with political actors. Engagement of international community in developing and/or promoting capacity of leadership at all levels of governments including elected local governments. Sadly, many of our existing political governance programmes are of technical capacity development type, often without addressing into deeper socio-political issues and realities. Political parties can take the MDG agenda closer to the people, and parliamentarians can bring back the people's feedback and insights to the floors of the parliaments, also to establish and/or strengthen accountability mechanism and combat corruption.

The UNDP Asia-Pacific Human Development Report 2008, titled Tackling Corruption, Transforming Lives, concludes that corruption undermines human development and efforts at poverty alleviation by diverting goods and services targeted for the poor to well-off and well-connected households who can bribe officials. The action-oriented report examines a spectrum of corruption in the Asia-Pacific region and recommends a seven-point action plan, including concerted international efforts to implement the United Nations Convention Against Corruption, setting benchmarks for the quality of institutions, strengthening civil services, promoting codes of conduct in the private sector, establishing the right to information and supporting citizen action. The report also recommends that police, social services and natural resources be targeted as top priorities for anti-corruption campaigns.

We have already passed the midway point for meeting MDGs, yet remain far from their fulfilment. The UN Secretary General labelled 2008 the year of the 'bottom billion'. However, if we fail to strengthen democratic governance engagements with the MDGs achievement process, we will not be able to meet their expectations. 'The legal empowerment report asserts that in the absence of empowerment, societies lose the benefits that derive from the free flow of information, open debate, and new ideas. This again can directly contribute to unchecked corruption at the cost of undermining democracy. The innovative role of law, this context is critical. As Hernando de Soto, Commission Co-chair, puts it “The law is not something that you invent in a university the law is something that you discover. Poor people already have agreements among themselves, social contracts, and what you have to do is professionally standardise these contracts to create one legal system that everybody recognises and respects.”

The view expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations, including UNDP, or its Member States.

The writer is lawyer and researcher by training, is Knowledge Management Specialist and Facilitator of the Democratic Governance Practice Network at the Bureau for Development Policy in UNDP New York.