Human Rights watch

Saudi Arabia: Implement proposed labor reforms

Government should immediately abolish sponsorship system

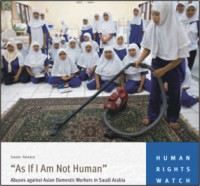

Saudi Arabia should immediately implement its proposed reform to the kafala sponsorship system and extend labor protections to domestic workers, Human Rights Watch said today. The government has considered these measures for years without concrete action, but has recently renewed attention to the subject. A Human Rights Watch report released on July 8, 2008, “'As If I Am Not Human': Abuses Against Asian Domestic Workers in Saudi Arabia” documented how gaps in the current labor law and the kafala system expose migrant domestic workers to a range of abuses, including long hours without days off, physical confinement in the workplace, and little power to collect owed wages in labor disputes.

Saudi Arabia should immediately implement its proposed reform to the kafala sponsorship system and extend labor protections to domestic workers, Human Rights Watch said today. The government has considered these measures for years without concrete action, but has recently renewed attention to the subject. A Human Rights Watch report released on July 8, 2008, “'As If I Am Not Human': Abuses Against Asian Domestic Workers in Saudi Arabia” documented how gaps in the current labor law and the kafala system expose migrant domestic workers to a range of abuses, including long hours without days off, physical confinement in the workplace, and little power to collect owed wages in labor disputes.

“These reforms would provide workers with important protections, and could serve as a model for the region,” said Nisha Varia, senior researcher in the women's rights division at Human Rights Watch. “They should be implemented as soon as possible to prevent future cases of abuse.” The kafala (sponsorship) system ties migrant workers' visas to their employers, and means employers can deny workers the ability to change jobs or leave the country. Human Rights Watch interviewed dozens of domestic workers who said their employers forced them to work against their will for months or years.

The government's proposal would make recruitment agencies rather than employers the immigration sponsors for foreign workers. An alternate proposal from the National Society for Human Rights calls for the Saudi government to assume the role of sponsor. Either change would mark a significant improvement to the current system, but both would require rigorous monitoring.

“The government should also move quickly to amend the labor laws,” said Varia. “Domestic workers deserve the same rights as other workers.” The Human Rights Watch report received extensive media coverage globally and in Saudi Arabia, including outlets such as Al-Hayat and Arab News. Although many Saudi citizens have expressed concern about the issue, some government officials and recruitment agents were critical of the report.

A few critics, including the Saudi Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Saudi Human Rights Commission, and the National Human Rights Society, minimized the number of abuse cases in Saudi Arabia, called attention to crimes against employers by domestic workers, and claimed that abusive employers are punished adequately. “It's a real shame when Saudis try to deflect attention from abuses against domestic workers by arguing that employers are the victims or focusing only on those women who have positive experiences,” said Varia. “They miss the point Saudi employers have better access to the justice system, while domestic workers face many barriers due to gaps in labor laws, immigration restrictions, and poor access to translation and their consulates.”

These groups also accused the Human Rights Watch report of being one-sided and failing to acknowledge proposed reforms, although the report explicitly pointed out that many migrant domestic workers have positive experiences in Saudi Arabia. The report in fact devoted a section to the proposed reforms and featured them prominently in its summary and recommendations.

“Many of the criticisms of the report are simply not accurate,” said Varia. “We invite Saudi officials, human rights advocates, labor recruiters, and the public to read the report themselves instead of relying on hearsay about its findings or automatically rejecting its conclusions.” Human Rights Watch highlighted the Nour Miyati case as an example of egregious abuse. In her case, there was ample evidence of the abuse, including medical records and the employer's confession, and her employers were not punished. Human Rights Watch also noted that employers can fail to pay domestic workers for years and face only the light penalty of a ban on hiring workers in the future.

Human Rights Watch research in Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and the Philippines has found that many migrant workers are aware of the risks in migrating abroad, but take the risk given a lack of viable options for employment at home. “Instead of denying the problem, the government should focus on preventing and responding to cases of abuse, whether it is one case or 10,000,” said Varia.

Source: Human Rights Watch.