For Your information

Loopholes in the Labour Act, 2006

Bikash Kumar Basak

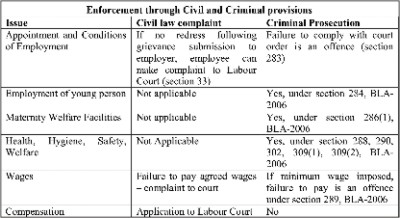

The Bangladesh Labour Act, 2006 (BLA 2006) has opened the door for the “aggrieved” workers, and trade unions to seek redress of criminal nature for breaches of labour law. It is well established that criminal, rather than civil, action is more effective in both deterring the potential wrongdoers from committing offences and also ensuring that they are held accountable. Under the new Act although employees can continue to seek direct civil redress from the Labour Courts for alleged breaches of the duties regarding appointment/employment conditions and payment of wages principal way of law enforcement for breaches of duties relating to health, safety, hygiene, welfare, maternity rights and child labour is through criminal prosecution.

Health and safety offences

Health and safety offences

Not only has the BLA 2006 introduced a wide-range of criminal provisions, the sentences that can be imposed following conviction are also much harsher than those contained in the old labour legislations.

In the old legislations no sentences of imprisonment were available for any health, safety and welfare breaches and the maximum fine was only 1000 taka. In the BLA 2006 there are five offences specifically relating to health, safety and welfare-the selling of unguarded machinery, failure to give notice of an accident, a breach causing death, a breach causing grievous bodily harm and a breach causing any harm (section 309, BLA 2006). In addition, there is a 'catch-all' offence that allows prosecution against “whoever contravenes or fails to comply with any provisions of the Act, or any rules made under it”. This offence would, for example, apply to any breach of the obligations involving health, safety and welfare, not already covered by the offences above. This offence is punishable with a fine up to Tk 25,000 [as per Bangladesh Labour (Amendment) Ordinance, 2008]. In this regard, it is to be noted that as per section 308 of the BLA 2006, a repeated occurrence of the same offence can result in double the fine or double the sentence of imprisonment prescribed for a single offence.

When there has been a breach of a duty imposed upon an employer, any one of the individuals defined as an employer can be prosecuted. In addition, when a company is prosecuted, according to section 312 of BLA 2006 “every director, partner, shareholder or manager or secretary or any other officer or representative directly involved in [its] administration” shall be deemed guilty unless he can prove that the offence was committed without his knowledge or consent or he tried his best to prevent such commission.

Changes to prosecution procedures

The BLA 2006 has brought about two important new procedural features relating to prosecution. Prior to the introduction of the Act, under section 64 of the Industrial Relations Ordinance, 1969 the Labour Courts dealt almost solely with disputes of civil nature (e.g. those relating to wages, terms and conditions of work, and compensation), most of which had to be brought by the workers themselves. Criminal cases (e.g. those relating to health, safety and welfare obligations) were to be processed by the Magistrate courts. Now, as per section 313 (1) of the BLA 2006, the Labour Courts not only have jurisdiction over civil matters but also criminal prosecutions.

The other important procedural change is that proceedings for any criminal offence can now be instituted not only by the Factory Inspectors but also by an “aggrieved person or trade union” (section 313(2)(A), BLA 2006). Workers, bereaved families or trade unions could not, prior to the Act, institute criminal proceedings against employers who breached their obligations set out in the law. The term 'aggrieved person' is not defined in the law, but it would almost certainly include (a) a worker injured as a result of unsafe conditions in breach of the Act or otherwise personally disadvantaged by a breach of the Act or (b) a member of a family bereaved by a death caused by any breach of the Act. An “aggrieved trade union” would, arguably, include a union whose members(s) are exposed to risks as a result of a breach of the law.

In this regard, factory inspectors can continue to initiate prosecutions.

Prosecution process

Section 314 of BLA 2006 states that criminal cases must be initiated in the Labour Court by means of a written “complaint” sent to the Labour Court within six months of the alleged commission of an offence. The outcome may vary depending on the person making the “complaint”. If it is an Inspector, the Court will probably immediately summon the defendant to appear before it; and if, however, the complainant is a worker or trade union, the magistrate will first examine him/her under oath (and possibly some further witnesses) to verify the credibility of the allegations, and only then, if satisfied, issue a summon. The normal process of criminal trial will then take place. In prosecuting these cases, the BLA 2006 says that Labour Court should follow “as nearly as possible summary procedure as prescribed in the Code of Criminal Procedure.” With relation to the trial of an offence, according to section 215(4), BLA 2006, “a labour court shall, while trying an offence hear the case without the members". So, in criminal prosecution, there is no scope for representation of workers and employers.

Improved access to justice for workers

This new right for workers and trade unions to prosecute cases allows them to enforce parts of the BLA 2006 that previously could only be enforced by a factory inspector. Whilst reforms still need to be made within the Inspectorate, it is now possible for workers and trade unions to enforce health, safety and welfare obligations imposed upon an employer through initiating criminal proceedings, without having to wait for an inspector to take action. The increased levels of sentence attached to many of these offences makes prosecution, or the threat of it, for the first time, a real deterrent.

Labour rights NGOs, legal aid organisations and trade unions now have the possibility of a new range of strategies to improve workplace conditions. If, for example, there is a factory with health and safety conditions in clear breach of the requirements of the BLA 2006, NGOs can use the threat of prosecution as a way of levering improvements. If the employer fails to make the necessary changes, a criminal case can then be initiated. Depending on the circumstances, the employer could be told that the case will be withdrawn if the employer finally makes the requisite improvements. If the employer fails to do this, then the legal aid organization can move forward with the prosecution. Any convictions, particularly those that result in imprisonment, could have a significant deterrent effect upon other employers. This strategy is unlikely to be successful if the 'aggrieved person' is an individual worker still employed in the same establishment. It would be much more preferable if the worker is no longer working for the employer. It would be even more preferable if there is a trade union that can file the case as an 'aggrieved trade union'.

However, the effectiveness of the strategy depends on whether there is a trade union with members at the relevant workplace since individual employees are likely to feel very vulnerable to take this kind of action. However, former workers might be able to take action in relation to conditions to which they were subject.

Continuing obstacles to safety enforcement

This new 'right' discussed above provides some real new opportunities for enforcement but obstacles do remain for effective enforcement of the law.

Labour Courts

There are only seven Labour Courts in Bangladesh three are based in Dhaka, two in Chittagong, one in Rajshahi and one in Khulna - compared to 1300 magistrate courts. Each of these courts have jurisdiction over different parts of the country. The 3 Dhaka courts have jurisdiction over Dhaka Division; the 2 Chittagong courts have jurisdiction over Chittagong and Sylhet Division; the Rajshahi court has jurisdiction over Rajshahi Division, and the Khulna court has jurisdiction over Khulna Division and Barishal Division. So, physically accessing the courts for justice is clearly much harder. An extreme example of this relates to Labour Act offences that take place in Sylhet. Since there is no court in Sylhet, cases have to be brought in the Chittagong courts - literally the other end of Bangladesh. The need for additional labour courts in other major industrial towns and cities is clearly necessary.

However, even though there are far too few Labour Courts, these courts may well prove to be a much more appropriate forum for prosecuting these cases than magistrate courts. In a Labour Court there is a specialist judge with good understanding of labour issues and this may help speedy disposal of cases.

Absence of lawyers in the Factory Inspectorate

Prior to the BLA 2006, when the levels of fines were low and sentences of imprisonment were not available, prosecutions were rarely contested. The employer just paid the small fines. However, now, since almost all convictions can result in an imprisonment, employers will almost certainly contest cases. This will have a big impact on inspectors who file criminal 'complaints' since they would have to be present during the trial. Due to the small number of inspectors, this could create a real problem that could be avoided if the Inspectorate employ lawyers who could represent the inspectors in courts whereas according to section 220, BLA 2006: “Except appearance for giving evidence, in all other cases, before a Labour Court or a Labour Appellate Tribunal, a person may perform the filing of an application giving attendance or any other work either by himself or by a representative or lawyer duly authorised by him in writing.” So, sufficient number of lawyers must be appointed to represent the inspectorate.

The writer is Programme Officer, Bangladesh Occupational Safety, Health and Environment Foundation (OSHE).