Law Watch

Q & A on the hidden reality of children in domestic work

Q & A on the hidden reality of children in domestic work

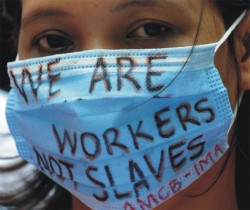

The recently approved ILO Convention No. 189 and Recommendation No. 201 on decent work for domestic workers aim to protect and improve working and living conditions of millions of workers worldwide, who have few if any labour rights. Many are children who spend long hours working as domestic helpers, performing tasks such as cleaning, ironing, cooking, minding other children and gardening instead of being at school. ILO News spoke to ILO experts Martin Oelz (TRAVAIL) and José M. Ramírez (IPEC) on the current situation of child domestic workers and how the new Convention and Recommendation can help impact their lives.

How do you define “child domestic work” and roughly how many children fall within this category worldwide?

The term “child domestic work” refers to domestic tasks performed by children (i.e. persons below 18 years) in the home of a third party or employer. Given its hidden nature, it is impossible to have reliable figures that show the extent of child domestic work. However, the latest data by the ILO's Statistical Information and Monitoring Programme on Child Labour (SIMPOC) shows that, globally, at least 15.5 million children (age 5 to 17) were engaged in domestic work in 2008. This represents almost 5 per cent of all economically active children in this age group. A little more than half of them fall within the age group 15-17 years, while the rest, or 7.4 million, are 5-14 years old. The number of girls in domestic work far outnumbers that of boys. Asia, Africa and Latin America are the regions most affected by this problem.

Why is child domestic work a “hidden” problem and why is it so difficult to tackle?

This phenomenon is often hidden and hard to tackle because of its links to social and cultural patterns. In many countries child domestic work is not only accepted socially and culturally, but is also regarded in a positive light as a protected and non-stigmatised type of work and preferred to others forms of employment especially for girls. The perpetuation of traditional female roles and responsibilities, within and outside the household, as well as the perception of domestic service as part of a woman's “apprenticeship” for adulthood and marriage, also contribute to the persistence of child domestic work as a form of child labour. Child labour occurs when children are below the minimum age of employment (normally 15 years) and when, irrespective of their age, the work performed by the child is hazardous. In other words, when the nature of the work or the circumstances in which it is carried out is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of the child.

What are the root causes of this phenomenon?

There are many root causes of domestic child labour, but in broad terms we can differentiate between “push and pull” factors”. Among the first, there are poverty and its feminization, social exclusion, lack of education, gender and ethnic discrimination, violence suffered by children in their own homes, displacement, rural-urban migration and the loss of parents due to conflict and/or disease. Among the latter we can talk about increasing social and economic disparities, debt bondage, in addition to the perception that the employer is simply an extended family and therefore offers a protected environment for the child, the increasing need for the women of the household to have a domestic “replacement” who enable more and more women to enter the labour market, and the illusion that domestic service gives child workers an opportunity for education.

What are some of the hazards that children domestic workers face?

The hazards linked to child domestic work are a matter of serious concern. The ILO has identified a number of hazards to which domestic workers are particularly vulnerable and the reason it may be considered to be one of the worst forms of child labour. Some of the most common risks children face in domestic service include: long and tiring working days; use of toxic chemicals; carrying heavy loads; handling dangerous items such as knives, axes and hot pans; insufficient or inadequate food and accommodation, and humiliating or degrading treatment including physical and verbal violence, and sexual abuse. The risks are compounded when a child lives in the household where he or she works as a domestic worker. These hazards need to be seen in association with the denial of fundamental rights of the children, such as, for example, access to education and health care, the right to rest, leisure, play and recreation, and the right to be cared for and to have regular contact with their parents and peers. These factors can have an irreversible physical, psychological and moral impact on the development, health and wellbeing of a child.

How does the new Convention and Recommendation on decent work for domestic workers contribute to the fight against domestic child labour?

The new Convention (No. 189) compliments the provisions of two other key ILO Conventions on child labour: Convention No. 138 on Minimum Age and Convention No. 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labour. The new Convention (No. 189) explicitly states that member States of the ILO shall set a minimum age for domestic workers consistent with the provisions of Conventions Nos. 138 and 182, and not lower than the minimum age established by national laws and regulations for workers, in general. The new Recommendation (No. 201) reinforces this by calling for the identification, prohibition and elimination of hazardous work by children, and for the implementation of mechanisms to monitor the situation of children in domestic work.

Children trapped in domestic child labour from a very young age are likely to have had no or insufficient access to education. At the same time, child domestic workers above the legal minimum age have a reduced chance of continuing with education. The new Convention thus calls on member States to take measures to ensure that work performed by domestic workers under the age of 18 and above the minimum age of employment does not deprive them of compulsory education, or interfere with opportunities to participate in further education or vocational training.

Source : ILO.