Law Event

Social justice mission in legal education

Anisur Rahman

Ali Akbar khan in his article "Political Economics of Reforms" opined that reforms directed at changing the situation of the poor can only be brought with measures that are not lucrative to the upper strata of the economic situation as then they would be compelled by their own nature to engulf all of it. Reform can only be brought with a design that offers things unwanted by the Haves so that they get delivered to the Have Nots.

Ali Akbar khan in his article "Political Economics of Reforms" opined that reforms directed at changing the situation of the poor can only be brought with measures that are not lucrative to the upper strata of the economic situation as then they would be compelled by their own nature to engulf all of it. Reform can only be brought with a design that offers things unwanted by the Haves so that they get delivered to the Have Nots.

Professor Prof. Rahmanur Rahman, Chairman of the Human Rights Commission, spoke in the same vain in his speech on “Reflections on Social Justice Mission in Legal Education of Bangladesh” in Eastern University, Dhaka on 9th June. The programme was arranged as part of the regular Lecture series convened each month by the Department of Law of the University. Held in the Auditorium of the University the session was chaired by Professor Dr. Borhanuddin Khan, Advisor of the Law Faculty and Dr. Nurul Islam, Vice Chancellor of the university graced the occasion as the Chief Guest. While Chairperson Department of Law, Ishrat Azim Ahmad rendered the vote of thanks.

By portraying the redundancy of the current obsolete legal education system, in his words “in house system of learning, overwhelmingly textual and extensively legalistic” Prof. Rahman argued that the graduates passing every year are nothing more than mere legal technicians lacking the sensibility to read between the lines there fore rendering the legislations “black letter laws”. Seemingly radical and preposterous idea at first sight, the proposal is in fact long due and a silent movement that dates almost 3 decades. The legal education system prevalent in Bangladesh lacks the all important connection with politics, sociology, anthropology, history, science, philosophy, psychology, international relations; a suicidal approach for a multi disciplinary subject such as law. Law is fundamentally a discipline that stems from and thrives in the real life problems of the people, mostly poor people, and real life problems do not come in single focused uniforms rather are entrenched with the niceties of the day to day life.

The absence of or even lack of understanding and compassion on the lawyer's part, who is to defend another person, the detached, impersonal approach that has so become likely of the vocation by default leads to a system that does not change the situation of the incumbent.

Prof. Rahman's proposition stands on four concrete grounds. Firstly, legal education has ceased to become multi disciplinary as both the students and the teachers find that it would not bring them any good in the professional sector. A supposition that tells us that the lawyers and the actors in the system has successfully achieved the goal of measuring everything in terms of the fruit they yield and not just any fruit rather, financial gain and pushed the social responsibility that is thrusted upon them by the nature of the vocation to the corner. Secondly, the real people, working in the periphery, fighting with the difficulties of every day life are not aware of their legal rights and processes, the same processes that are supposedly designed for them and thus are not being empowered at all. In this situation it befalls upon the students and practitioners to take up the mantle and be the protector but since due to the classroom oriented teaching system, no real connection is ever made with the student and the reality, thus the lack of passion and empathy. Thirdly, there has not been a growth in our domestic jurisprudence and a strong inclination towards accepting the law as it is- a reluctance to read between the lines or to interpret them. In his words “our students are at their best are mere technical interpreters. They do not philosophize. They do not question or challenge existing paradigms”.

Napoleon once said that he has done a lot of things but would only be remembered for one thing, that is the French Penal Code. Throughout the drafting process he read and re- read the whole thing and sent it back to table to ensure that the provisions are clear and easily understandable by the layman, so that law does not become the monopoly of an elite group, apt to understand it. Our legislations suffer from the same ornamental words and a way of twisting and turning them before chucking them out, and it seems by pointing out the reluctance in reading between the lines, Prof. Rahman wanted us take notice of this issue also.

And fourthly, law has always been pro rich and anti poor, a tool that has always come handy to protect the rich whereas it is the poor that needs the protection most. Prof. Rahman asks the students to stand up and question the present set up if they are not happy and to bring changes through what he calls “Rebellious Lawyering”. The concept of rebellious lawyering demands a socially relevant legal education which would in the end usher in people friendly laws, rule of law and access to justice.

As he states, his philosophy is much influenced by the thoughts of Prof. N. R Madhava Menon who with the help of Indian Bar council and Government has been working towards realizing his vision. The vision of educating lawyers that would stand up for the common man, empower the indignant, work for the community and is certainly not the personification of the shrewd blood sucking lawyer, so feared by the people. The interpretation of that vision along with Prof. Rahman's own ideology in Bangladesh and where it stands to day has been a long journey fraught with censure, obstructions and strong oppositions often resulting in denial.

At the end of the day all these efforts, programmes and talks are a way of reminding us, the actors in the legal education system, both student and teachers alike that, this is a discipline that entails social responsibility with it, a responsibility that can not be shaken off or be ignored.

Prof. Rahman's Arithmetic Dream envisions that in 20 years there would be 140 to 150 rebellious lawyers in the High Court dedicated to the cause of the humanity and poor and urges the institutions providing legal education to initiate such steps. But one must ponder, whether the day has come, for all the law schools of the country come together to create a curriculum and a teaching method that would not only fashion the susceptible, green mind of a student to look at the law as it ought to be, not as it is and ignite the fire within to fight for a cause. The people of this country are denied justice on a daily basis and there is a lot to do, to help them, to make tangible difference if all came together. The question is whether the day of calling has come and gone and whether it is the time when we start walking on the road that has been painfully paved before us.

The writer is Assistant Professor Faculty of Law, Eastern University.

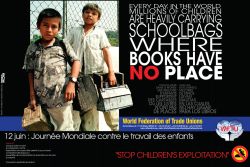

No child labour

Ending child labour is a matter of human of rights and social justice. Step up the fight; do not relent: this is the call addressing the tenth anniversary of the World Day against Child Labour. The worldwide mobilization against child labour is paying off with important progress achieved over the past decade. Today there are 30 million fewer child labourers worldwide than a decade ago. The sharpest decrease has been among younger children, in particular girls.

Conventions on child labour are among the most widely ratified of all ILO Conventions. More and more countries have established national plans to tackle child labour or have introduced laws prohibiting hazardous work by children. And in consciousness, policy and practice, crucial linkages are increasingly being made: between child labour and poverty, and between the elimination of child labour and universal access to quality education.

Decent work for parents means that children are less likely to fall victim to child labour."

Said by Juan Somavia, Somavia Director-General of the ILO while giving message on the occasion of child labour.

However, the road to full eradication is long and challenging. The reality remains extremely worrying. The bottom line is that 215 million children are still trapped in child labour, 115 million of them in the worst forms. Our latest estimates indicated an increase of 20 per cent in child labour among young people aged 15 to 17, mainly involved in hazardous work.

We can put together a combination of policies founded on respect for those principles and rights so that children can be free from child labour and have the chance of a better life. Effective education and training policies backed by social protection measures can produce significant increases in school enrolment and a decline in child labour. Decent work for parents means that children are less likely to fall victim to child labour. And better enforcement of national laws, including strengthening child labour inspection and monitoring, enhancing victim assistance and improving prevention strategies are critical to success.

In a world of growing inequality we must link policy agendas with basic standards of fairness and do right by the world's children. In a world of incredible wealth, the means exist to end child labour. On this World Day with will and solidarity let us renew our efforts, stay the course, and reach the goal.

Source: Hrea.org.