|

Food for Thought

Afghanistan

The Long Nightmare

Farah Ghuznavi

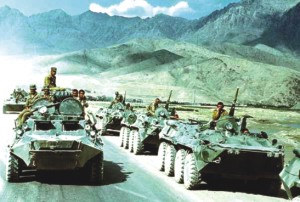

According to many commentators, the current war in Afghanistan actually looks promising; in comparison to the amphitheatre of death that is Iraq. This is worrying on a number of levels. Firstly, because the history and culture of the Afghan people gives little reason to believe that any external intervention will be successful in the long run. This is, after all, a country, which has proven ungovernable by everyone from the British over a century ago, to the Russians a few decades ago. Indeed, the closest that Afghanistan has ever had to an effective central government (of sorts) has been during the cruel and unenviable regime of the Taliban. Secondly, of course, the fact that the Afghan scenario should appear in any way hopeful probably says more about the disastrous invasion and occupation of Iraq, than it says about the situation in Afghanistan itself. According to many commentators, the current war in Afghanistan actually looks promising; in comparison to the amphitheatre of death that is Iraq. This is worrying on a number of levels. Firstly, because the history and culture of the Afghan people gives little reason to believe that any external intervention will be successful in the long run. This is, after all, a country, which has proven ungovernable by everyone from the British over a century ago, to the Russians a few decades ago. Indeed, the closest that Afghanistan has ever had to an effective central government (of sorts) has been during the cruel and unenviable regime of the Taliban. Secondly, of course, the fact that the Afghan scenario should appear in any way hopeful probably says more about the disastrous invasion and occupation of Iraq, than it says about the situation in Afghanistan itself.

The extremism, misogyny and savage punishments that characterised the period of Taliban rule, meant that there were many Muslims and non-Muslims who felt that, quite apart from the events of September 11th, there were sound moral justifications for intervening in that particular situation. In particular, the regime's medieval ideas of justice, the brutal treatment of women and incidents such as the destruction of the Buddhist statues at Bamiyaan (against the pleas of many learned Muslim scholars who exhorted the Taliban to spare this priceless cultural treasure) occasioned outrage in many quarters. By providing a safe haven for Al-Qaeda, the Taliban merely created a more immediate incentive for the intervention that followed.

But the fact is, fighting a war however righteous or justified, requires a clear understanding not only of the motives behind such an act, but also a strategic approach in prosecuting that war. Britain's involvement in previous Afghan wars (1838-42 and 1878-80) sprang from motives that were all too clear i.e. putting in place a regime that did not favour the Russians in this strategically important crossroads of Asia.

|

For many Afghan farmers, growing poppies is the only source of income. An alternative crop has still not been identified. |

The issue of “regime change” was also part of the plan behind the attack carried out in 2001. The nature of the Taliban, as well as the attack on the World Trade Towers prompted that action in favour of regime change. The stated aims included bringing democracy, prosperity and humanitarian aid to a country that had been at war for nearly three decades. A secondary aim was supposedly to address the grotesquely unjust situation of Afghan women.

The question is whether any of these aims was actually realistic? For one thing, a key policy of western governments has been to destroy opium production, Afghanistan being the world's greatest source of the white poppy. But this clearly contradicts the aim of bringing prosperity to the country, since growing poppies has long been a key source of income for Afghan farmers. Around 90% of the world's heroin currently comes from Afghanistan, and to date a profitable alternative crop has yet to be identified.

There is also the question of how to establish a firm central government in a country that has never respected or responded well to any centralised authority. Afghanistan is a highly disparate land comprised of different tribal groups vying for political power, and mostly ruled by powerful regional warlords. Furthermore, the status of women, as in many other societies, is subject to constraints imposed by reactionary cultural and religious elements, and the situation is unlikely to be effectively remedied by any “quick-fix” solutions.

Given these realities, it is not altogether surprising that all is not well in Afghanistan today. The foreign troop presence numbers around 35,000, who are part of the Nato-led alliance; these include about 5,600 British troops, of whom around 4,300 are located in Helmand and the remaining 1,300 in Kabul. While British troops are ostensibly there to provide security and help rebuild the country, in Helmand province they are also heavily involved in counter-narcotics activity. This is bringing them into conflict not only with ordinary Afghans who rely on poppy cultivation for income, but also the warlords whose power and wealth is derived from the drugs trade.

To make matters worse, the resurgent Taliban are proving to be ferocious adversaries, despite the alliance troops' access to superior military facilities and hardware. Pakistan's failure to stop the Taliban attacking from across the border has been a bone of contention between the Afghan and Pakistani governments for some time, but no solution has yet been negotiated to halt Pakistani support for the militants, despite repeated denials from the government there that they are not providing a haven from which the Taliban can engage in cross-border activity.

In Helmand province in particular, the area bordering the Helmand river is proving to be a lethal fighting territory for British troops. The Taliban operate in areas where they have the advantage, including civilian compounds and irrigation ditches where tunnels have been created to hoard weapons for battle. In the words of one British officer, “It is quite important that we don't underestimate the enemy… We have operated with some success in the north, but we are dealing with a different dynamic down south…very much their home ground. They are really good. Their fire is accurate and they stay and fight.”

According to another military officer, the Taliban have no hesitation in using unconventional measures to further their aims. In one village, immediately after a local elder had insisted that there was no Taliban presence in the area, the insurgents opened fire, and fighters emerged from the poppy fields to encircle the village. Some of the “women” lifted their burqas to reveal armed men! Unsurprisingly, British soldiers in the area have experienced heavy fighting and suffered a number of casualties.

The nature of the Taliban's engagement with British forces needs to be seen within a context where British commanders have been given permission to carry out “aggressive operations including pre-emptive strikes” in their areas of deployment, which means that they have the power to take offensive action almost on par with American forces, and far more than troops from other Nato countries. The similarities between the US and UK roles can be seen in the comment by the British Defence Secretary, who stated in April that there would be overlaps between the British military activities and the US-led operation "Enduring Freedom". According to him, if the Taliban attacked British forces “we will defend ourselves and if defending ourselves… means taking pre-emptive action we will do that.”

Meanwhile, the British government has already exceeded its budget for Afghanistan (having so far spent in the staggering sum of 1 billion pounds). An announcement in early 2007 was made that 1,000 extra troops would be sent there and an estimated 250 million pounds would be added to the defence budget to cover the cost of this reinforcement. This has led to protests that Britain is contributing disproportionately to this campaign, while other Nato allies are failing to carry their share of the burden.

To date, countries such as Germany, France, Italy and Spain have not shown great enthusiasm to be part of a full Nato complement in Afghanistan. This has inevitably led to deep frustration within the alliance that the brunt of the fighting has been borne by troops from just a few countries. This is borne out by casualty figures, which are as follows: US (365), UK (61), and Canada (50), as opposed to Germany (18), France (9) and Italy (9) (UK Independent).

Nato commanders have been complaining for some time that they do not have enough troops to inflict a decisive defeat on the Taliban, with one senior officer describing the Afghan mission as a “Cinderella operation”, compared to the resources lavished on the occupation of Iraq. This also raises a valid point about the extent to which resources are being properly allocated to the two conflicts, given the coalition forces' singular failure to achieve anything in Iraq (beyond plunging it into an ungovernable civil war).

Western military personnel are not the only ones unhappy about this campaign. The Afghan population has suffered heavy casualties in the course of the fighting between the alliance soldiers and the Taliban. Civilians are regularly being killed in the crossfire between the insurgents and the thinly spread forces of Britain and its allies, particularly when Nato ground forces call in air support. In mid-June, Afghan officials claimed that 25 civilians, including women and children, were killed in an air strike in northern Helmand. For a change, President Hamid Karzai spoke out against his western allies, saying, “In the past five or six nights and days, we have had huge civilian casualties… caused by Nato and coalition carelessness.”

Shortly after that, in early July, an estimated 100 people were killed as a result of air strikes, nearly half of whom were civilians including women, children and the elderly. This brings the civilian death toll to several thousand, and is not making any positive contribution to winning hearts and minds, as even western military sources have conceded. Additionally, a disturbing trend is the growing incidence of suicide bombings in the region, which in combination with attacks and military operations have killed nearly 3,000 people across Afghanistan this year.

Clearly, five years after its arrival in Afghanistan, Britain finds itself with an entirely different role from that envisaged at the time when it entered the conflict. It is supporting a shaky government, led by President Karzai. He is a leader who has so far failed to adequately impress the different factions as a national president, or been able to convincingly place himself above tribal loyalties. As the UK Independent has pointed out, without intending to, the British and other alliance forces “risk being seen not as liberators but occupiers”, a position further reinforced by their involvement in anti-narcotics operations and the destruction of the opium crops on which many Afghans depend for their livelihood.

While the Taliban has successfully regrouped and transformed into a formidable enemy - however “asymmetric” the popularity of western forces has been repeatedly undermined by the ramping-up of a Nato bombing campaign against the insurgents, which has led to hundreds of civilian casualties. It raises the distinct possibility that the US-led operation entitled “Enduring Freedom” involves a sight more endurance for Afghans than whatever freedom it allegedly provides to them.

And there's no end in sight. According to the new British ambassador in Kabul, the task of rebuilding Afghanistan as a stable nation could last “a very long time”; indeed, he suggests, it may take as much as 30 years! This bleak prognosis cannot bring any comfort to the alliance military forces or the Afghan people, however much it may gladden the hearts of the Taliban…

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007 |

|