|

Special Feature

Ending the Battle for Freedom

Four decades after the nine-month-long, bloody war of liberation, a legal battle is on to try the forces who took a brutal stand against that very freedom.

Julfikar Ali Manik

It was half past ten in the morning of July 26, the proceedings for the long awaited trial were about to begin. At the courtroom of the International Crimes Tribunal, set up to try the war criminals of the Liberation War of 1971, the intensity of emotions was palpable. The sky was a bright blue, the sun hot and brilliant, as if reflecting the light on the excited faces of those present in the Tribunal courtroom. They were visibly overwhelmed at witnessing the first moment of this historic event, for which the nation has been waiting for 39 years.

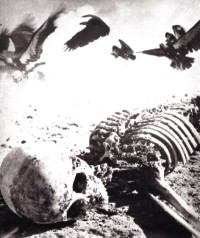

A war is not over until justice is served. Photo: Naibuddin Ahmed |

The proceedings of the pre-trial issue -- the arrest order against four leaders of Jamaat-e-Islami -- was no less significant as it was the beginning of a process long overdue. Premier Sheikh Hasina is pledge-bound to try the war criminals of 1971, a pledge that was endorsed by the people through the ballot in December 2008. The proceedings, so soon into her tenure, have come as a surprise to some who thought it was a “mission impossible”, with powerful national and international friends of the alleged war criminals expected to try to foil the move.

The top leaders of the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami were produced before the Tribunal just after a week of arrest warrants being issued against the four -- Motiur Rahman Nizami, Ali Ahsan Muhammad Mojahid, Muhammad Kamaruzzaman and Abdul Quader Molla. They will go down in history as being the first to sit in the dock of the Tribunal for alleged war crimes, crimes which they have denied in a history of the Liberation War they have tried to distort ever since the killing of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

Yet the fact that the Jamaat leaders have never accepted the independence of Bangladesh is obvious even in Quader Molla's referring to the Liberation War as a “period of chaos” when he was produced before a court in a different case just last month. The phrase “period of chaos” was widely used by anti-Liberation elements since the war who, in the name of religion, wanted to protect Pakistan at the cost of the lives and honour of the freedom-seeking Bengalis. On September 15, 1971, Nizami was quoted by the Daily Sangram, the mouthpiece of Jamaat, as saying, “Every one of us should assume the role of a Muslim soldier of an Islamic state and through cooperation to the oppressed and by winning their confidence we must kill those who are conspiring against Pakistan and Islam.” Nizami, incumbent Ameer of Jamaat, was the then president of Islami Chhatra Sangha, the student wing of Jamaat at the time and the architect of Razakar, Al-Badr and some other auxiliary forces of the Pakistani occupation forces. Mojahid, who was also one of the top leaders of Chhatra Sangha and the mastermind behind Al-Badr in 1971, told the media in 2007, “In fact, anti-liberation forces never even existed.”

These are old-fashioned attempts of anti-Liberation elements to distort history and confuse the new generation through propaganda claiming even that the war was in fact not a war of liberation but a “civil war”. If history continues to be distorted in this way, it may soon become difficult to differentiate truth from lies. As former chief justice Mostafa Kamal told this correspondent in 2007, “Now it is being said that no war criminal exists in the country. Maybe after some time it would be said that the Liberation War never took place. All this will mean we will be deprived of the real history.”

Indeed, the history of the Liberation War has been politicised in such a way that children learn different versions of the same historic events in accordance with the changes in political regimes. Bangladesh is possibly the only country in the world which had to solve a political battle over the proclamation of Independence, in court. (The court gave a verdict declaring that it was Sheikh Mujib, not Ziaur Rahman, who proclaimed the independence of Bangladesh on March 26, 1971).

Bangladesh has become a country of impunity, where not only have perpetrators of war crimes, assassinations and other grievous crimes got away scot-free, but where they have actually been rewarded by different governments/political parties in power, giving the message that the criminals are above the rule of law. BNP chairperson and former prime minister Khaleda Zia made Nizami and Mojahid ministers of her cabinet. Earlier, her husband former president Ziaur Rahman had rehabilitated them and their party Jamaat, endorsing religious and communal politics in the process. Ziaur Rahman also rewarded the killers of Bangabandhu after assuming power illegally and abusing the original Constitution. The actions of our leaders have all but proven that powerful wrongdoers are always above the rule of law. The completion of the trial of the killing of Sheikh Mujib and his family and execution of the verdict was a historic win -- one step towards correcting our historic mistakes. The trial of the war criminals is the next step.

While excitement reigns in those both within and outside of the Tribunal, questions are rife among those unable to observe the proceedings firsthand. Will it finally be possible to complete the trial? Is it possible to get enough evidence against the war criminals 39 years after the war? How long will it take to complete? Will powerful foreign countries put pressure on the government to stop the proceedings? Will it be possible to finally punish the war criminals? In order to ensure a fair and transparent trial, the Tribunal administration will be allowing local and foreign observers to witness the historic proceedings. Accommodating the huge number of observers expected, within the limited space may be an issue, however. Live telecasting of the proceedings, as has been done in some trials abroad, may be an option.

The journey of the Tribunal is the beginning of the end of the issue of trying the war criminals of 1971. It will not be easy and there are expected to be enormous attempts to thwart the process. The recent move of the government with regards to the amendment of the Constitution and the Supreme Court's verdict declaring the Fifth Amendment illegal has paved the way towards restoring the secular spirit of our Constitution which was the dream of those who gave their lives to build the country anew. The trial of the war criminals will decide the fate of anti-Liberation, communal and religion-based political forces who have until now found a safe haven in the country, the birth of which they had opposed.

A training of the Razakar forces in April 1971. Photo courtesy: Banglar Muktir Sangram by Aftab Ahmed.

The trial is a golden opportunity to correct our historic mistakes and failures of the past. But this time, there is no room for error. Ensuring justice will be the only way to show respect to the mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers who gave their lives and sacrificed their honour with the dreams of building a secular “Shonar Bangla”.

On the Road to Closure

The start of the trial of the war criminals gives hope to the survivors of the Liberation War and families of the victims who have been waiting for justice for 39 long years.

Kajalie Shehreen Islam

The last memory Shaheen Reza Noor has of his father is from back in December 1971. Jessore, his hometown, had fallen recently and several people had come to his father to share the news of impending victory for the nation. Noor's father, eminent journalist Sirajuddin Hossain, had said, “Yes, we will be free, but will we be able to handle our freedom? Our people lack sanity, let's hope that we don't make a mess of the freedom we have won.” That same day, the Al-Badr forces picked up Hossain who was never heard from again.

Thirty-nine years later, Sirajuddin Hossain's words ring true in his son's ears. “He absolutely pinpointed the problem,” says Shaheen Reza Noor, President of Prajanma '71, an organisation formed by the children of the martyrs of the Liberation War and assistant editor of the Daily Ittefaq.

Almost four decades into the nation's bloody struggle for independence, the wounds of war remain fresh and unaddressed. War victims and affected families have not even had the consolation of justice being done to the perpetrators of the war crimes. Murderers and rapists have roamed free and even reigned in a nation they had fought against the birth of. Thirty-nine years into the genocide perpetrated by the Pakistani army aided by local collaborators, the process of getting justice has just begun.

“We the families of the martyrs have been demanding justice from 1972,” says Shyamoli Nasreen Choudhury, wife of martyred intellectual Dr Abdul Aleem Choudhury. “The movement gained momentum in the 1990s with the formation of the Ekattorer Ghatak Dalal Nirmul Committee with Shaheed Janani (mother of a martyr) Jahanara Imam at the helm. Now we are hoping that the matter will finally be resolved but there are many obstacles to be overcome along the way.”

Renowned sculptor and a war victim of 1971, Ferdousy Priyabhashini says that though victims and their families are grateful for the initiative on the part of the government, the slow progress is causing them to lose hope. “We realise that things cannot be hurried, but every effort must be made to ensure a fair and transparent trial,” says Priyabhashini. “What is taking so long? The perpetrators have been identified. Enough evidence has been submitted. We have good lawyers who just need to be hired. We just need the government to be sincere and to follow through on its promise. They have the mandate of the people including families of martyrs and the young generation; they have to follow through on their pledge. The process must be sped up.”

There are several impediments to the process, however. Shahriar Kabir, writer, activist and convenor of the Platform for Supporting International Crimes Tribunal Dhaka, points to three factors hindering the smooth progress of the process of justice. “Firstly, members of Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh have infiltrated the administration and are hampering the process.” In Kabir's view, though some politicians are saying that the trial is not against Jamaat but the war criminals, they are one and the same. Jamaat as a political party opposed the Liberation War, he points out.

Families of the martyred intellectuals demanding justice from Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in March 1972. Photo: Rashid Talukdar

Secondly, according to Kabir, while there is no doubt as to the sincerity of the government in wanting to try the war criminals, seriousness is another matter. “The government is unaware of many things, of the rules and techniques of such procedures, which they must know and implement if an effective trial is to take place,” says Kabir.

“Thirdly, it may be that there are groups within the government itself which want to drag the process up to the next elections. But this will have a boomerang effect. The current government has a three-fourth-majority mandate of the people, largely the result of an election pledge to try the war criminals. The trial must be completed by this government and in this term because if it isn't, the government will not be voted back to power with such a mandate.”

In Kabir's opinion, the Tribunal as it now stands is a weak body that will not be able to deliver. “There is an inadequate number of prosecutors and investigators,” he says, “we need at least 25 of each. We currently have seven lawyers, four of whom are not even doing the work they are being paid to do, let alone work from their own sense of what is right. We have very good lawyers in our country, we have to hire the best of the best -- the war criminals will be bringing in the best lawyers from abroad and we must have lawyers good enough to fight them. International organisations too have offered their services, but we must ask for their assistance if we require it. They can provide expertise and training of which we are in dire need.” The issue must be addressed politically at the local level and diplomatically abroad, so that the world knows about the trial, impediments to it and how they are being overcome, says Kabir.

There are logistical problems too, he points out, the most obvious one being that of space constraints. “The trial is a huge task which will require an enormous amount of work. A lot of research has to be done, a lot of documents and reference books need to be stored, this requires a library which does not exist. Neither is there enough space to accommodate the observers from human rights organisations around the world who will be attending the trial.” The war criminals, their prosecutors and observers from organisations which back them will be on the lookout for any loopholes and will try to thwart the process, warns Kabir. “We have to be very careful not to give them that chance.”

Finally, there are resource constraints, says Kabir. “The Tribunal cannot function independently if it is not financially independent. It cannot be dependent on the government and its various ministries for funds. The government should have nothing to do with the trial. It has set up the Tribunal and it will be the plaintiff in the case, it has no other role.”

At the personal level, Shahriar Kabir, who lost two of his cousins -- writer Shahidullah Kaiser and his brother filmmaker Zahir Raihan -- during the war, says the affected families are becoming frustrated. “The process is taking so long that the victims and eye witnesses are dying. Those who remain are frightened for their own security and what will happen if the trial does not come through and they are left to the mercy of the war criminals. They must be given protection, provided with armed guards if necessary, as well as economic security if the situation is such that they cannot go out to earn a living,” says Kabir.

Shaheen Reza Noor fears that, while the war criminals are “morally bankrupt”, they are financially very strong and may use this to try to buy their freedom. “Those involved in the case must be completely committed,” says Noor, “so that they cannot be swayed. The State has a historic responsibility.”

“To those who are concerned about the human rights of the perpetrators,” Noor continues, “it is important to keep in mind that the killers did not consider the human rights of the people they killed mercilessly, neither were human rights activists able to do anything to stop them at the time. The rights of the killers are not a priority.”

“We can forgive natural disasters over which we have no control and we can try to rebuild our lives after they have occurred. But we will not forgive the war criminals; they are killers; they must be tried and punished,” says Ferdousy Priyabhashini, who has been waiting for justice for more than half her life.

It is not only the struggle of the victims and their families but for the nation as a whole, says Shaheen Reza Noor. “In the same spirit that we fought the war of independence, we must fight for bringing the perpetrators of the war crimes to book. We must keep the pressure alive, we must keep the spirit alive. We the people are the strength of the movement.”

“The goal is not to seek vengeance but justice,” says Shahriar Kabir. “We must break the culture of impunity in Bangladesh; we must prove that it is not a society ridden with crime and criminals, that we are a civilised people.”

Almost four decades into independence, the nation for which people like Sirajuddin Hossain and Ferdousy Priyabhashini gave their lives and sacrificed their honour is still grappling with their hard-earned freedom. For those who have survived, the beginning of the long-awaited trial of the war criminals comes as a flicker of hope, dimly lighting up the long and difficult road to closure.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010

|