|

Art

Symbolising Freedom

Freedom is an enduring motif in sculptor Hamiduzzaman Khan's work

Fayza Haq

Hamiduzzaman Khan, Chairman of the Department of Sculpture, Dhaka University, has contributed in a big way towards the inclusion of sculpture, especially in steel, in today's architecture. Incidentally, his solo began on December 4 and continues to usher in art buffs till December 14.

Most of his work involves portrayal of freedom fighters, symbolised with flying birds or even elongated human forms of guerrilla fighters during the Liberation War. These remind one of the sculpture pieces of Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti, which was recently the toast of the US art market.

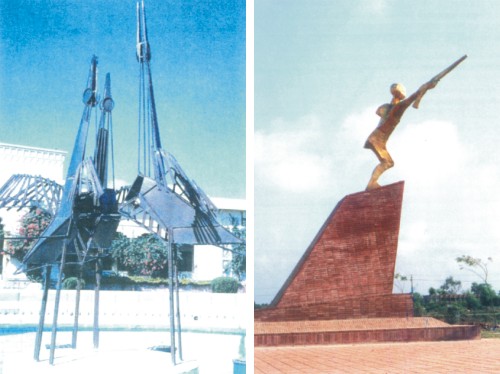

Hamiduzzaman’s work at a five-star hotel in Dhaka. Photo: Courtesy

But Khan has had to face a considerable amount of struggle and strife before he could reach the height that he has today. Speaking at his house, over noodles and tea, with sculptor wife, Ivy Rahman doing the honours, he spins out the irresistible yarn of how he ended up as a sculptor nonpareil – in a country which has no reliable or easily affordable stone to speak of; and wood can easily be destroyed due to the humid tropical weather. Knowing full well that ours is largely a Muslim country–where human figures and portrayal of animal and bird forms are sometimes questioned– he still took up sculpture in a big way.

Never daunted, this Professor with his jaunty steps and salt and pepper hair, as young student of Fine Arts had had a serious road accident, when a truck hit his head. The nasty hit and run incident took place in front of the DU in the late sixties. At that time, in Bangladesh, there was no reliable institution for neuron-surgery in Dhaka, which the young sculptor could have access to. As such, he was advised to go overseas. He went on route Dakar, Africa, to Scotland by sea. At Dakar he came across African carvings in the form of elongated, oval masks in black wood, which were reasonably cheap, and which he collected at lib.

He then proceeded on for his treatment in Edinburgh, Scotland, where he was to rest and recuperate for some months. This gave him time to visit the famous English art museums, like the British Museum and galleries, where he studied mummies, along with statues of the Egyptian Greek and Roman times. “For four months, as I roamed about on the English streets, I was also exposed t o modern English sculpture of the highest forms, like that of Moore,” says Khan, “In Paris and Rome I had the opportunity to study the Renaissance at St Peter's, masters like Michelangelo. I got to see the Louvre and other museums, which was different from seeing books on art in the libraries back home. Montmarte and Montparnasse heightened my desire to be a true artist as my mind and heart desired. I wanted to study the masters – both old and new–so as to study the best of each cultural height at it's their creations. One knew of sculpted forms from Moinamati, Paharpur and Harappa from studies in Dhaka. I wanted to leave no stone unturned in my quest to learn as much as possible and probable, under the circumstances, and as luck would have it.”

L-R: ‘Bird Family’, Bangabhaban. ‘Shangshaptak’,

Jahangirnagar University. Photo: Courtesy

The sculptor studied painting from the then College of Arts and Crafts. “I had Zainul Abedin, Safiuddin Ahmed, Aminul Islam, Mustafa Manwar as my guides and teachers. Appointed as a teacher, I had the incentive and the responsibility to work full steam ahead, without looking back. I felt trusted and admired. As luck would have it, my teachers, helped me obtain the government scholarship to Barodha, India for two years (1974-1976). I was in my mid twenties. In my Master's result I got the top position. There, with the help of my teachers and guides, I had an exposition of my sculpture work, which were figures on the ground like the wounded and half devoured corpses of the liberation war of Bangladesh. I had informed my teachers that the subject of my display would be the 'Remembrance'. This was like an installation, with the figure on a piece of cloth on the floor. This had never been done before in the subcontinent,” says Hamid.

He was too young to participate as a soldier in the Liberation War. But he had witnessed and heard enough reports to make the world aware of the genocide by the merciless Pakistani army, which had brutally maraude his homeland. In many of his sculpture pieces even the one at Barodha (India) it is the massacred and mangled human form that he presented to the viewers in his first exhibit, and this won a first prize in the exposition at Mumbai, celebrating “Twenty-five years of Barodha”. FM Hossain came there too and sought him out as his entrée had moved the master artist, as it was unusual and eye-catching. It was also mentioned in the press for its marked individuality. This gave him confidence to forge ahead in his quest to tell the world in stone and steel of the ruthless massacre that took place in his country.

Meanwhile, the Shilpakala Academy in December, 1976, held an exposition on the national scale, inviting all the sculptors of Bangladesh, limited as they were in number. It included Abdur Razzaque, Syed Abdullah Khalid and Anwar Jahan. Here Hamid got the best award, and naturally encouraged him on to work confidently and with more determination. By this time he was an established teacher, having done sculpture for 13 years, with the Liberation War in mind. “I was then told to make a sculpture piece for Sylhet Cantonment, which was 12 feet high. Since I had worked in bronze in India I was confident. I got the help of a factory called Bitack,” Khan says. The payment, for this, incidentally, was Taka five lakhs, and was given by Amin Ahmed Chowdhury, who was then the Chief of Sylhet Cantonment.

“From 1980-1981 I worked on a piece for Bangabhaban. This was a bird done in a modern style, with metal pipes. This replaced a fountain, built in the British colonial period. Having finished this, I went to the US to enlarge my horizon. I chose to make a school for sculptors, at Lexington, besides Park Avenue, at New York. Having worked there for a year, I got an assistantship. I was asked to give a sculptor piece in piece of US $ 4,000. Hence, I stayed in the US for a year, travelling, learning and exchanging as much of ideas as I could, within that span of time,” he says.

Khan did a solo at Washington DC with the pieces he had managed to finish in the US. This was in 1983 with the help of the Bangladesh Embassy. Hamid says that what he learnt from the US was modern sculpture in various forms. True, he says, he'd seen Henry Moore's work in Edinburgh, way back, and he was exposed to modern sculptor at England and the rest of Europe too. Yet, in the US he saw the cream of the latest trends in sculpture, especially those that had been placed outdoors. This was so mostly in New York, says Khan. He also says that many exhibitions opened there.

|

Hamiduzzaman Khan |

During his early days as a sculptor, he did not find many sculpture enthusiasts. He found neither patrons nor sculpture enthusiasts in the 70's, when he started out, Khan says. There were confines and restrictions. With time and exposure, appreciation for sculpture developed gradually in Bangladesh.

Khan did work on the freedom fighters in front of Jahangirnagar University too. This was called “Shangshaptak”. It is placed in front of the library and is made of metal sheets. The patron was the University authorities and was done in 1989. Another work of his on the same theme can be seen at the Zia Fertilisers. This is about 50 feet high.

Khan winds up his tete a tete by saying that following the call of his mind and heart as an artist hell bent, so to put it, to express his thoughts and memories followed his spirits, sacrificing many material things that one naturally yearns for. When he started out, says Hamid, working with steel and stone was not a trifling matter, but in about 12 years the world looked brighter for him, as sculpture began catching up, with more galleries and patrons coming up, like “Shilpangan's Faiz Ahmed and Bengal Gallerys' Litu Bhai apart from the Shilpakala Academy, The British Council and other centres for culture, which had the necessary space for exposition of sculpture in stone, burnt clay and wood. Today even the young enthusiasts of the Britto Trust go in for sculpture, in their experimental ventures in far-flung areas of Bangladesh.

Today, says Khan, the outgoing architects of Dhaka try to accommodate sculpture in or in front of their multi-storeyed buildings. They realise that sculpture heightens the beauty of the offices for banks, insurance companies, and even universities, colleges etc. One knows private homes in the metropolis, with sophisticated tastes, to keep metal sculpture in their living rooms. “A lot of young businessmen spend a fair amount for construction of buildings. For them to budget for the sculpture is not out of reach, as it is for the average bourgeois art buff,” says Khan.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |

| |