Special Feature

Stories of the Masses

Every family who lived through the nine tumultuous months of 1971 in Bangladesh has a story to tell – be it of struggle, fighting, fear, torture or betrayal

Tamanna Khan

|

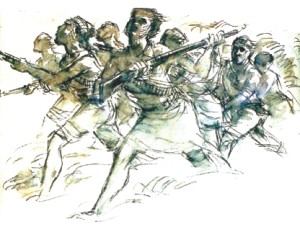

Zainul Abedin, Freedom Fighters. Photo: bengal foundation |

When Samad Mia took the job of a gatekeeper at House-14, Mirpur-2, one of his demands to his employer, besides the meagre salary and Eid bonus, was that on every December 16, he be given a Bangladeshi flag that he would hoist up on the roof. This, he felt, was his duty towards his motherland -- the land he had liberated from the grips of the Pakistanis in 1971. Rimi, the daughter of his employer recalls this passionate freedom fighter: “On the morning of December 16 every year, as the boom of cannon fire initiated the Victors Day, he would get up on the roof and hoist the flag.” Rimi feels proud to be able to know a freedom fighter so closely as she did not get the opportunity to hear the story of liberation, from her own grandfather who was a traffic inspector at Mymensigh station in 1971, and had helped smuggle an entire train to the freedom fighters during the war.

Sawon is more fortunate than Rimi as he gets to hear the story of the battlefield from his father, freedom fighter Mohammad Abul Hossain Jinnah, who fought in Sathia Zila, Pabna. “My father left home for training at Shiliguri, India on June 30, with a squad that was referred by Professor Abu Sayeed. He received guerrilla training on use of rifle, explosive and grenade, bridge destruction and so on. On July 31, under the leadership of Major Omprakash and Captain Ali Singh, he took part in his first operation on the front,” says Sawon proudly. He then relates the story how his valiant father, who now works at a garments factory, had blown off a bridge at Panighat Pahar, which was used extensively by the Pakistani army and was always guarded by Razakars.

|

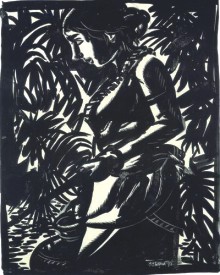

| Samarjit Roy Chowdhury, The Oath

of the Liberation War. Photo: www.deshforum.com |

Although not every family had a member who went to fight for his/her motherland, those who lived through the nine tumultuous months of 1971 in Bangladesh, still has a story to tell – be it of struggle, fighting, fear, torture or betrayal. Nahid Ara Jafri relates how her father Siddique Ullah who was a Bangladesh Bank official at that time, helped deliver arms to the freedom fighters. A friend of her father had requested him to take a weapon to Rajshahi, where her father had been transferred. The friend disguised as a cobbler met her father at the Aricha jetty, when the family was on their way to Rajshahi. At the other side of the jetty, their car was stopped at the check post but was not checked thoroughly, when her father showed his visiting card. However, there was a Razakar, who refused to let him go. When his father complained about the Razakar to the army official, the official slapped the latter and apologised to her father for the Razakar's behaviour.

Bipodhari Pala, a 60-year-old potter, living in Rayerbazar for decades, had to leave home on March 25, 1971 in fear of the Pakistani military to the nearby Samrashir village. “Our homes were then looted by many of our Bengali Muslim neighbours. I have heard that the military took away the idols of the nearby Rayerbazar Akhra Mandir but later they returned it. Though they did not burn the temple they had burnt many of the nearby houses irrespective of whether those belonged to the Hindus or the Muslims,” says Bipodhari. Unlike Bipodhari, sculptor Paritosh Pala and his community was protected from the atrocities of the Pakistanis by their Muslim Commissioner, Sonamia Sarker. “He was very influential and he boldly told the Pakistanis to leave the Hindus of Sirajdikhan alone,” recalls Paritosh, who at that time used to live with the Pala potter community in Bikrampur. Paritosh remembers giving shelter to the seven hundred refugees who had run away from Dhaka in face of Pakistani military attack.

|

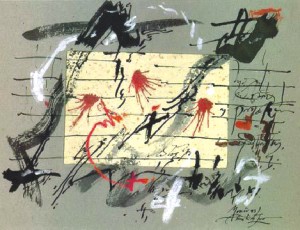

Shahabuddin Ahmed, Victory-1. |

Most people, especially those with a political background had to flee their city or town homes in fear of military torture. Besides, villages were thought to be safer places because of their remote nature. M Morshed, who had lost one of his elder brothers in the War recalls how his family had problem finding shelter in the town they lived in. “My parents were both NAP (National Awami Party) activists and everybody knew them in Naogaon. After two of my brothers went to join the war, my parents had to leave home with my other brothers and sisters. But people in the neighbourhood who knew them were afraid to give them shelter in fear of being blacklisted by the Pakistanis. At last they took shelter at a nearby village in the home of a stranger.” M Morshed's brothers were only in their teens when they went to join the War. “My eldest brother Mujahidul Islam was seventeen and my second brother, Abdullah-Al-Mamun, who was caught while carrying out a grenade operation at a Pakistani Army camp in Naogaon, on August 26 and later killed, was only sixteen,” says 35-year-old Morshed, who never got to see his fearless martyred brother.

|

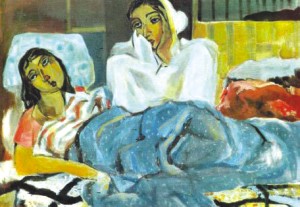

Quamrul Hasan, Woman Freedom Fighter. Photo: www.deshforum.com |

However, staying in one place for too long was also not feasible during those times. People were constantly on the move. After escaping the massacre of March, Rebeka Sultana with her family had returned to their Pabna home only to leave it again towards the middle of April for her maternal uncle's home in another village. “My cousin's father-in-law was a member of Shanti-Bahini and he informed us that there may be an army raid in that village. So we, along with my uncle's family, went to another remote village near Badai Khal. We walked the entire night and reached a house where we sat to rest for a while eating puffed rice and listening to the radio. Suddenly we heard the sound of firing,” says Rebeka. It was a surprise attack by the Pakistani military, which left them completely deranged. In an attempt to flee, Rebeka and her sister got separated from their family. “There was an open field through which the military were advancing with open fire. The only way to escape was to cross a lake by walking over a shakon (narrow bamboo bridge). While crossing, I saw an elderly couple falling off from the shakon. I wanted to help them but could not as our own life was at risk then,” says Rebeka with sorrow.

Unfortunately even the lake could not save the two sisters, a young Pakistani army came after them in hot pursuit. Rebeka who had taken first aid training during the Indo-Pak war of 1965 told her sister to lie down on the ground during the brush fire and in between the pauses, make a run for shelter. “Fortunately, there was a brickfield and a pond ahead and we planned to hide behind the chimneys. I looked behind and saw the Pakistani soldier only ten yards away, aiming at us with his sten gun. Without a second thought I jumped in the pond and just then the bullets escaped us by a second,” relates Rebeka, who was later saved by a Hindu family living nearby.

|

Monirul Islam, Genocide. Photo: www.deshforum.com |

Some people were too young to remember the incidents of the war clearly. Instrument player Komol, who was only a nine-year-old boy, living in the old part of Dhaka at Banglabazar, vaguely remembers meeting a group of elusive young men at the roof of the house adjacent to his. “I used to see them in the morning often cleaning their black sten guns, before nightfall they would be gone. One of them named Khokon, called me one day and asked whether I want to hold the gun,” he says. Komol now thinks that they might be one of the guerrilla troops who were sent on mission to Dhaka and probably they had used the old house hidden among the confusion of old Dhaka buildings as their hideouts.

Unlike Komol, Rifat Hossain, who was sixteen years old then, clearly remembers the nine months she spent in the captive atmosphere of Dhaka. “My father, a renowned journalist of Sangbad, Syed Nuruddin, was at the government service during war-time. We received an order from the military regime that children of all government officers should take the matriculation examination otherwise they would face dire consequences. I had stopped going to school after March 25; although the school was open the attendance was very poor. I had no preparation and did not want to sit for the exam. Yet Abba (father) told me to go just for the sake of going. My centre was at the Cantonment Adamjee School and army officials surrounded the entire compound. I felt so terrified that I started crying, so my father requested the army officials to let him sit outside the gate. They did allow him to sit but they kept their guns pointed at us throughout the duration of the examination,” remembers Rifat.

|

Kazi Abdul Baset, The Unbearable Life of 1971. Photo: www.deshforum.com |

December 16 almost came as a release order for Rifat. “It was such a feeling that I really cannot express it in words. We were living like captives in our own homes, in our own city, every moment passed in uncanny anticipation. When we got the news we were so happy. Ours was a conservative family yet the thrill and excitement of the December 16, brought us all out on the streets in joy,” reminisces Rifat, while a tint of the excitement finds its way back in her voice 39 years later.

As December visits Bangladesh again, her sky, roads, building tops drenches in the red and green of the flag that 65-year-old year old Abdul Khalek, had fought for at Mehendiganj, Barisal. This renegade freedom fighter, who had fought under the command of the local police inspector, till the last of their ammunitions, now has difficulty even remembering Victory Day in his daily fight to survive. Yet, he tries to pass on the history of his valour in broken words to the new generation while paddling his rickshaw through the busy streets of Dhaka.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |

| |