| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 21 | June 03, 2011 | |

|

|

Theater

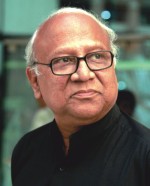

Thriving Theatre Fest Rifat Munim Anational theatre fest creates opportunities for the local troupes to feature their latest productions and thus share their responses to long-standing social or aesthetic issues. An international theatre fest, on the other hand, comes up with a different scenario altogether. It provides local theatre activists and enthusiasts with the rare chance of interacting with activists from other parts of the world and vice versa. Furthermore, it makes for a congenital atmosphere for all the participating countries to exchange ideas, especially those that relate to the current trends of thematic and formal experimentations in theatre. With this broader picture in mind, Bangladesh Centre of the International Theatre Institute (BCITI) organised the 10-day-long 1st Dhaka International Theatre Fest (DITF) that ended on May 30. Although local troupes dominated the stage, spontaneous participation of the foreign troupes seemed to have ushered Bangladesh in a new era of theatrical exchange that, with the passage of time, would embrace more and more foreign troupes under its wings and extend the scope of cultural exchange significantly. “I know only a handful of Asian troupes participated in this festival. But it is just the beginning and we will keep it up drawing more and more countries within our ambit. In the next years, we will invite troupes from Europe and Africa. In fact, we envision that in the next 50 years this festival will turn out to be the biggest theatre festival in the world,” says Ataur Rahman, theatre personality and president of BCITI. The festival was patronised by the ministry of cultural affairs in association with Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy. This is for the first time in Bangladesh that the funding for a theatre festival came from the concerned ministry. If this trend continues, theatre activists believe, Bangladesh will soon turn out to be the theatre hub of Asia. “We have all the potentials to lead a worldwide theatre movement. Our young directors and actors are doing so good that I think they are quite capable of leading an international theatre event,” opines Rahman.

The last international theatre fest that had brought together a rich variety of foreign theatre troupes and delegates on Bangladeshi soil was the International Ibsen Seminar and Theatre Festival (IISTF) in 2009. The IISTF with its seminars, workshops, and highly experimental theatrical productions of Ibsen's plays from across the world, pulled off an international festival on a much larger scale. But what narrowed down its scope of effective theatrical interactions and encounters was the fact that it was focused solely on the modern Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen and his plays. The DITF, however, was divested of any such delimiting factors, and all the participating troupes, whether local or foreign, had the freedom to choose and present a subject matter in its own characteristic or experimental way. This resulted in the staging of brilliant plays that were as much diverse in the choice of themes as in their modern, avant-garde formal experimentations. Besides, most of the plays featured in the fest were produced within the last two years, having a fresh aura to all of them. To begin with, the Singaporean troupe Buds Theatre Company staged 'Shades' on the inaugural day. A love story between a Muslim girl and a Muslim boy in Singapore, the play entails other stories that are marginal yet indispensable parts of a multi-cultural context. Bringing out the tension existing between religious and post-modern values as a consequence of globalisation, the play focuses on the dimensions of identity for a Malay community which is a Muslim minority amonst a Chinese population in Singapore. The Hong Kong-based play '8 Times 8', jointly produced by Asian PEF and FM Theatre Power, revolves around the female protagonist named Promise and symbolises her physical journey to show how she transforms from one state of mind to another. In the beginning Promise, a China born woman brought up in Hong Kong, tries to wear off her Chinese identity but in the end she reconciles with it and becomes a social activist dedicated to the cause of the have-nots. The Nepalese production 'Maila Dot Com' by Theatre Mandala is about an undefined relationship between a 25-year-old woman who owns a coffee shop and a 13-year-old boy who works for her at the shop. Then there were the Indian productions Streer Patro by Natyabhumi and Dakghar by Kalakshetra. The former is based on one of Tagore's most remarkable feminist short stories in the same title and the latter is the adaptation of Tagore's famous play of the same name.

Despite all the innovative productions of the foreign troupes, the local productions were at the centre of all attention. Language barrier, perhaps, accounts for one reason as non-Bengali plays cannot properly communicate with the local audience. Side by side with plays that uphold social causes, a persistent characteristic of Bangladeshi theatre, there were top-notch experimentations. Aranyak Natya Dal, a highly politically conscious theatre troupe, proved with its 'Eti Jocasta' and 'To be or not to be' that it can also excel in dealing with the classics. The first play is based on Sophocles' Oedipus and the second on Shakespeare's 'Hamlet'. Both of them, however, depart from the original storyline and reinterpret the classics from the perspective of contemporary society. Kohe Birangana by Manipuri Theatre, which is based on Michael Madhusudan Dutta's Birangana Kabya , and Mahajaner Nao by Subachan Natya Sangsad, among other plays, also won plaudits for their socially committed themes. All the above-mentioned plays were directed by promising young directors. The commonest feature of the local productions, like that of the Indian ones, was that a good number of the plays were either written originally by Tagore or based on his poems, letters or fiction. The most fascinating of these was Theatre's Muktodhara, a play in which Tagore repudiates aggressive nationalism and technological advancement that lead to warfare. In Theatre's rendition, the play takes on a contemporary look and the theme of peace and love against war and hatred becomes all the more relevant. Then comes the experimental play Banglar Mati Banglar Jol by Palakar which efficiently dramatises Tagore's six-year-long stay in the eastern part of the erstwhile Bengal i.e. Shilaidaha, Shahjadpur and Potishor. Written by Syed Shamsul Haq, the play is based on a set of letters written to his niece Indira Devi, that were compiled in a book titled Chhinnapatra. The play Magaz Samachar by Theatre Art Unit is another adaptation of a Tagore's poem titled Juta Aubiskar. The Rajshahi-based troupe Anushilon performed the acclaimed Tagore play Rother Roshi.

Even the foreign troupes spoke highly of the local productions. Yet, one fundamental question remains: how much of the foreign plays was comprehended by the local activists and vice versa? One could only sidestep this aspect at the peril of undermining the main objective which was to strengthen and establish theatrical ties amongst the countries. If we fail to communicate through our plays, then it is unlikely that we will ever make meaningful exchanges. That 'Shades' and '8 Times 8' were performed in English is a very positive sign since a lingua franca appears to be the only alternative that can bridge the linguistic gap. Likewise, in order for the foreign troupes to communicate with our plays, local troupes should either go for sub-titling facilities or consider performing in English. “Verbal and physical languages are mingled in theatre. While the verbal languages are culture-specific, the physical languages are universal. So I agree that verbal language acts as a barrier and a lingua franca can partly bridge that gap. But a play represents a culture and every culture has its own making of rituals and language. When we translate it, those distinct rituals and linguistic traits lose lustre. Yet, we are thinking of making use of sub-titling devices in future to get over with the communication problems,” says Rahman.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |