| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 23 | June 17, 2011 | |

|

|

Obituary Abstraction and Utopia in Mohammad Kibria Mustafa Zaman

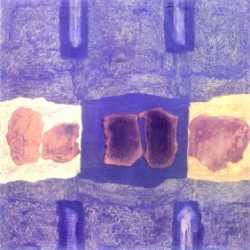

One of the pioneers of abstraction in this clime, whose non-representative prints and paintings have been for many the measure of Modernism, Mohammad Kibria is no more. He has breathed his last on Tuesday morning at a hospital in Dhaka, 7 June 2011. Kibria's quietist position in the social sphere complemented his works that were primarily grounded in a subdued set of aesthetic variables consisting of mute colours, measured application of delicate textures and nondescript shapes and a composition to put these elements in harmonious agreement. He has been a revered figure for his works that has mostly been conceived as a reservoir of mute visual energy. His sincere effort in basing his entire oeuvres on almost 'zero degree' aesthetics by skirting round all kinds diversions – aesthetic and otherwise – has apparently helped congeal his reputation within the first couple of decades of his career – 1960's and -70's. Vigorously active till the end, Kibria's choice of colours and textural configurations had a decisive impact on the Dhaka art scene, spawning numerous protégés; though, evidently, no one has so far been able to match his acumen and come even close to emulating the voice that never failed to strike a lyrical note. The high plateau he has been able to create still seems a long shot for many a follower and this perhaps has been the basis for the high esteem with which he has been held by successive generations of artists. Toned with a mute sense of expressivity, Kibria's creative universe was one of a recluse who had successfully been able to keep himself aloof of the socio-political realities of his time. His emergence as an abstractionist in the early 1960's signaled an auspicious beginning. Back then, among the younger generation of artists – his compatriots, who slowly but deliberately moved away from the location-specific Modernism of Zainul Abedin, Quamrul Hassan and S M Sultan, Kibria showed a single-mindedness towards abstraction which still remains unparalleled. Unlike his contemporaries, Kibria never veered towards any other mode of expression. Back in the 60's, the consensus to draw from Eoro-American abstraction of signature High Modernism seemed to have swayed all and sundry, including Kibria. He was arguably the leader of the Bangladeshi abstract movement and the only artist to have remained loyal to the language till his sudden demise.

In the 1950's, the decade after partition that had left Indian subcontinent divided along religious line, when the Muslims and the Hindus were forced to seek refuge across the newly demarcated border to escape intermittent purges following the bloody communal riots, Kibria came to Dhaka, displaced from his homeland Birbhum, now a district of West Bengal, India. Dhaka, the provincial capital of East Pakistan, soon became the epicentre for the culturally-inclined who began mobilising their aspirations and strengths to ensure a secular and progressive milieu. It is against this backdrop that in 1954 Kibria joined as a faculty in the institute that Zainul and his associates had already given a physical shape to. One who is now considered a stalwart of non-representative painting in Bangladesh, Kibria started out as a figurative artist in the 1950s. His position was that of romantic given to cubist tendencies; but soon this last layer of reality or the reference to it, whichever way one interprets it, was abandoned in favour of purist abstraction. If we are to construct a genealogy of his style, the earliest tendencies can be traced in some of his works produced during his study in the College of Arts and Crafts, Kolkata, from where he graduated in Painting in 1950. “There was a study work that everyone talks about in relation to Kibria's tendency towards abstraction. While depicting some scattered shrimp fries on a banana leaf as part of still-life study, Kibria came up with a rather unrealistic interpretation in water colour – a picture that emphatically brought into view the dampness of the given subject,” points out Nisar Hossain, an artist and a teacher of the Faculty of Fine Arts, Dhaka University, who had the rare opportunity to share some intimate moments with the taciturn artist. Nine years after graduation, during higher study at Tokyo University, Japan, from 1959 to 1962, Kibria's exposure to Western abstraction and its Japanese interpretations were decisive in his development as an artist. Guided by Hideo Hagiwara, a celebrated Japanese artist, Kibria's studentship under him was a way for the Bangladeshi young artist to learn to apply “precision and balance”, observes Syed Mazoorul Islam in a monograph on Kibria, published as part of the Art of Bangladesh Series by Shilpakala Academy.

To determine the knowledge-base of Kibri's language of expression one may resort to the artist himself. “Visuality and beyond – this jump is what turns a picture into a work of art,” this is how Kibria explained the origin of a particularly buoyant painting following his recovery from the heart disease he had suffered in 2002. The work titled “Composition with Blue”, an oil on canvas, contained all the essential elements of a Kibria, but it also had a resonance of natural phenomenon, showing a marked shift from his elemental paintings where a clement meteorology built through his personalised method usually conjoins with human pathos. If we are to cotextualise the artistic language that effectuated the continuous outpouring of creativity throughout Kibria's life, a duel tendency is externalised: the great 'outside' that is nature, or society and its cultural ambiance was either renounced altogether or brought into alliance with his 'inner domain'. Add to that the paradox of what can be captured and what lies beyond the capacity of representation. In fact, this paradoxical position was exactly the focal point in Kibria's works which often served as tools for their creators to discover what lay beneath the surface.

The essentialist bend of mind apparently seemed to have been consistent with his composure. A reticent man, who rarely spoke of his own life and art, Kibria was an urban mystic – one who applied his craft with caution and chose not to give away his work processes. Therefore, though primarily beholden to the colour-field painters of American origin, his works can never be considered as 'process painting' – which exactly what the major players of the New York school (of 1940's) became famous for. His works expressed state of mind, but the solipsist in him always preferred to find a voice through the tactile effects aiming to incite noiselessness and grandeur. The detraditionalisation and the secular utopia of constructing an autonomous world within the real world is what exactly Kibria have been made up of, and accordingly he, along with his compatriots, aligned with the concepts and ideals connected to such cultural inclinations. Born on January 1, 1929 in Birbhum, West Bengal, Kibria showed signs of talent much early on. The school that he had gone to facilitated art shows and cultural events through which he was exposed to works of the Indian giants – among them there were works of Rabindranath Tagore. There was a drawing teacher who took art very seriously and the main inspiration of Kibria, who instilled him the desire to become a painter, was the Headmaster Wazed Ali Chowdhury. It is through his intervention that Kibria later enrolled in the College of Art and Craft in Kolkata; he is the one who convinced the family to let him go and he si the one who prepared the artist of silence for the bigger things he was later to approach. At home, for his life-long devotion to painting he received Ekushey Padak and Independence Award. After his retirement in 1997, Dhaka University selected him as a professor emeritus in 2008. Mohammad Kibria – the artist and teacher – left behind his wife and two sons and a band of admirers. Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |