| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 27 | July 15, 2011 | |

|

|

Musings A Lamp Glows for Indira Gandhi Syed Badrul Ahsan

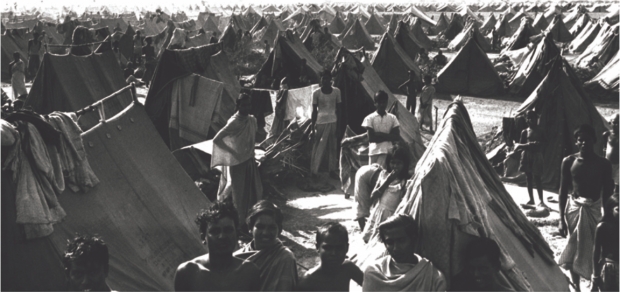

There are perfectly good reasons for Bengalis to remember Indira Gandhi. Forty years ago, as the state of Pakistan went for an extermination of lives and aspirations in occupied Bangladesh, it was India's prime minister who came to our defence. She could have sat back and watched the communal state of Pakistan devour a nation in cannibalistic fervour. She could have argued that the Bengalis, having voted for a division of India twenty-four years earlier, might as well carry on their struggle in their own fashion. That she did not, that she went beyond politics and well into the territory of the humane is what keeps us in thrall to her memory. There are all the terms of endearment we have for Indira Gandhi. She opened up the frontier and let our people, those escaping from the worst excesses of the Pakistan army, into Indian territory. Over the nine months of Bangladesh's War of Liberation, ten million Bengalis became recipients of Indian largesse and hospitality. By any standard, keeping so many refugees in her country despite all the economic tribulations it was itself subject to was a measure of Indira Gandhi's association with our cause. She carried her people with her in her defence of our cause. No Bengali with self-esteem, with a sense of history will ever forget the gesture. It was Indira Gandhi who understood early on that if the people of occupied Bangladesh meant to secure freedom for themselves, they would first need to formalise the structure of their struggle against Pakistan. And to that end, she quizzed Tajuddin Ahmed in early April 1971 about the plans the scattered Bengali political leadership had about handling the crisis. Obviously and as part of historical necessity, Tajuddin Ahmed and his colleagues first needed to put a government into shape before the Bengali struggle for freedom could be taken seriously. And thus the Mujibnagar government came to pass. For Indira Gandhi, the question of Bengalis waging a guerrilla war against the Pakistanis was critical. Beyond giving them shelter, beyond sympathising with them in their plight, it was necessary that they wage war on their terms against the marauders occupying their land. The Mukti Bahini, without Indira Gandhi's active support and without the backing of the Indian military, would remain a pipe dream for us. The setting up of training camps in places like Dehra Dun and the provision of ammunition to Bangladesh's freedom fighters were moves that called for great courage. Indira Gandhi did not flinch from opting for courage. The struggle for Bangladesh, she realised in the initial stages of the war, was also her struggle against monstrosity unleashed on a mission of murder, rape and plunder. At a time when Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger remained happy countenancing Yahya Khan's repression in Bangladesh; and China, having always proclaimed its solidarity with suffering people across the globe, looked the other way as Pakistani soldiers killed and raped in East Bengal, Indira Gandhi travelled to Europe, to America, to keep people posted on the life and death struggle of the Bengalis. On her initiative, the Soviet Union reached a deal with India in August 1971, one that guaranteed mutual support in case of attack on either party by another nation. More importantly, the Indo-Soviet pact was a concrete demonstration of the support Delhi and Moscow would yet provide to the people of Bangladesh in their war to rid themselves of Pakistan. In December of the year, as Indian forces assisted the Mukti Bahini in pushing Pakistan's soldiers into retreat, Soviet diplomacy at the United Nations kept all ceasefire moves at bay until the moment came for Bangladesh to stand liberated as a free nation. In the nine months of the war in 1971, Indira Gandhi did not waver in her support for Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. She reiterated throughout the duration of the crisis the need for Pakistan to engage with Mujib in any talks toward a settlement. In the later stages of the war, it was her persistent calls for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's freedom that was a factor in saving his life in Pakistani incarceration. Pakistan stayed its hand. Indira Gandhi could have gone on, after 16 December, to finish off what remained of Pakistan in the west. It was her decision to call a halt to war on 17 December which prevented rump Pakistan from collapsing in a heap.

Indira Gandhi, respectful of Bangabandhu's desire for Indian soldiers to go home in early 1972, told Bangladesh's leader that they would leave the newborn country in March. She was as good as her word. It was her gift to the Father of the Nation on the fifty-second anniversary of his birth. We do not forget Indira Gandhi. In the most trying moments of our history, it was her sagacity, her courage of conviction, her skilled display of leadership which kept us going. It is only moral, only proper that we record our deep gratitude to her for what she did for us. She defied the world because she found it infinitely better to defend our struggle. We were not her people and yet she made us her own. She was not our leader and yet we looked to her to speak for us in the councils of the world. She did. And we have kept a lamp glowing in homage to her. (Bangladesh's government has decided to honour the late Indira Gandhi for her contributions to our War of Liberation). The writer is Editor, Current Affairs,The Daily Star. Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2011 |