| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 41 | October 28, 2011 | |

|

|

Art

Establishing a Global Identity Bangladesh Pavilion, 54th Venice Biennale Samira Rahmatullah Parables, the first-ever Bangladeshi Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, showcases the work of five artists from the Britto Trust, an artist-led nonprofit organisation committed to developing avenues for the creation of experimental art in local communities across Bangladesh. The 54th Venice Biennale, one of the world's largest and most prestigious art shows, started on June 4 and ends November 27, 2011, presents art by 83 individual artists and 89 national Pavilions. As one of the national Pavilions, Parables features a genre of art that is highly conceptual in form and substance, and for many, presents a new face for contemporary art coming out of Bangladesh. Conceptual art presents concepts or ideas that take precedence over traditional aesthetic and material concerns. While this art form has existed in the West since the advent of modern art in the early 20th century, it is still an emerging trend in the Bangladeshi art scene. Bangladesh's bold take on conceptual art at the Biennale as well as the artists' ability to confront controversial issues such as social taboo, gender inequality and global conflict through their artworks, is a cause for celebration as well as a call for greater capital and support for our artists participating in the international arena. At a time when Bangladeshi artists are distinguishing themselves in international circles for representing a fresh promise of uncompromised originality, Parables will surely have a catalysing effect on the trajectory of contemporary art practices in Bangladesh, as our artists continue to develop a style and aesthetic representative of an increasingly globalised Bangladesh.

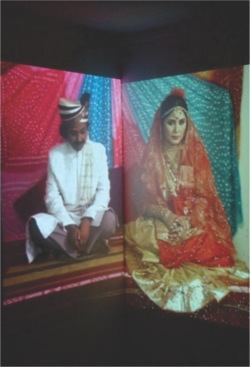

Stepping through the Pavilion's colourful door frame adorned with traditional craft, visitors are greeted by Kabir Ahmed Masum Chisty's sky of rainbow umbrellas arranged in a seemingly random fashion to create the effect of a technicolour cloud. This cheerful celebration of Spring monsoons ensues a feeling of warmth that is in sharp contrast to the other works in the Pavilion, which present a critical, sometimes disparaging examination of the perils and shortcomings of our society. For example, Chisty's second work, Quandary, is comprised of 70 small drawings of himself as the infamous gorgon of Greek mythology, Medusa, in constant and tormented battle with his serpents. This outward expression of humanity's inner conflict between good and evil becomes fully animated in a video projection positioned in the center of the display, depicting Chisty's outright anguish. The series serves as a chilling reminder of humankind's capacity for malevolence, but also of its power to persevere against its demons. Mahbubur Rahman explores a different kind of struggle than the one addressed by Chisty, in I was told to say these words, a decidedly decrepit installation of piglets made of fiberglass and cowhide, bound and caged in barbed wire. In an adjacent room, a similar structure holding several more piglets is accompanied by the mangled “moo” of a cow bearing an eerie similarity to the word “Ma”, as well as jarring neon signs spelling “Ma” in both Bengali and English script. This installation by Rahman is another very powerful work in the Pavilion for its ability to generate both a visceral and emotional response from the viewer. Eating pork is forbidden in Islam, our country's dominant religion. However, the tortured representation of pigs reminds us that the demonised and forbidden can often be at base something innocuous and helpless–in this case, baby animals. The work is a metaphor for the irrational prejudice of society, and of the taboos and social restrictions that incarcerate the freedoms of our most innocent, primal selves. Tayeba Begum Lipi's two works are also a reaction to social norms. The Bizarre and the Beautiful, a large metal hanger with 5 horizontal poles carrying 30 life-size bras built with razors, together with I wed myself, a dual-channel wedding video in which she plays the role of both bride and groom, address the problematic centrality of the body in definitions of gender and beauty. In the latter work, Lipi challenges the notion that femininity and masculinity are mutually exclusive by asserting her embodiment of both qualities. Her meticulous transformation from bride to groom and vice-versa, with its exclusive emphasis on the superficial aspects of appearance, raises further questions about the physical and mental aspects of gender. Imran Hossain Piplu reflects on the precarious future of civilisation as a whole in The Utopian Museum. Visitors are transported to a different time as they realise they are looking at an excavation site of present day society, dubbed “The Warrasic Period, 1600-2010 AD”. Fossilised remains of reptilian rifles, machine guns and missiles stand as the final vestiges of an increasingly militarised world, forcing viewers to reflect on the very real threat of annihilation from growing global conflict. Finally, Promotesh Das Pulak collapses time and memory in Echoed moments in time, a series of photographs of the 1971 liberation war, in which soldiers' faces are replaced with his own. Romanticized by veterans, the liberation war is considered by many to be the most promising time in our country's short history. Pulak recovers this promise by transforming the objective truth of archival photography into the subjective experience of a new generation. With Bangladesh again experiencing a time of swift and sweeping change characterised by extensive private sector development, rapid urbanisation, a growing middle class and increasing political stagnation, Parables ushers in a new era of art that may once again become politically charged. Indeed, with its outspoken emphasis on society's pitfalls, the Pavilion hints at a tipping point in the frustrations of a young, ambitious, and engaged generation of Bangladeshis. Thanks to unprecedented growth in the private and social sectors, Bangladesh today has one of the fastest growing economies in the world. With the rise of the nation, there is no doubt that its contemporary art, which still harbours a rare and innovative authenticity in an increasingly commercial industry, will earn a position of influence on the international stage. But for this to happen, the public, private and social sectors must channel significantly more capital and clout into developing Bangladesh's art infrastructure. Nonprofit organisations like the Britto Trust, Society for Promotion of Bangladeshi Art and the Bengal Foundation, all of which are mostly or entirely privately funded, have done a commendable job supporting the development of our artists and providing them with exposure through exhibits, grants and scholarships. If our artists are to realise their full potential on the international stage, we need more organisations like these; we need increased private and government sponsorship of Bangladesh's participation in international arts shows like the Venice Biennale; and finally, we need a great many more curators, critics, art dealers and galleries focused exclusively on Bangladeshi art. With the right level of support, Bangladeshi contemporary art can become a pioneering movement among developing countries, and prove itself a powerful medium for introducing a fresh, modern and globalised identity for Bangladesh to the world. Samira Rahmatullah is the founder of Alluvial Arts, an organisation dedicated to promoting Bangladeshi contemporary art in the San Francisco Bay Area, and is a member of the Board of Directors of The Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco's pre-eminent contemporary arts organisation.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2011 |

||||||||