| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 47 | December 16, 2011 | |

|

|

Cover Story 4: Art Independence as a point of return to the issue of art and society Mustafa Zaman

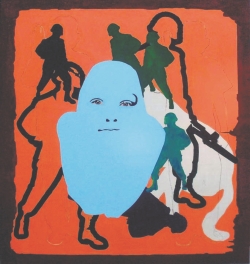

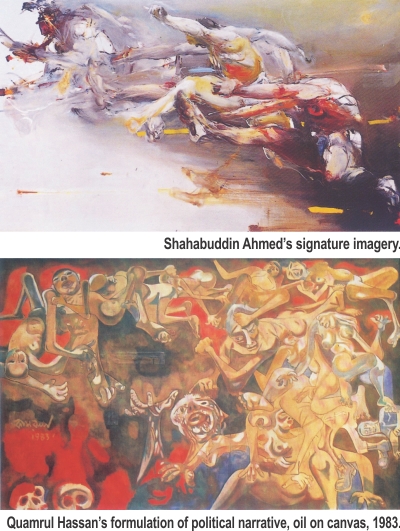

Years after independence, around 1983 to be precise, one of the country's pre-eminent modernists, also a first generation artist, Quamrul Hassan, embarked on a series of oil on canvas that puts to use a complex figural scheme to begin a parley with the political realities of his time. Three of the pictures in question now rest in the collection of the National Museum. In fact a portion of his life's oeuvres has been acquired by this national organisation in exchange of what some may perceive as peanuts. These works are among a few precious masterpieces which easily freight the trauma of the individual into the public domain, and they also testify to the power of the image to spark rethinking about both art and society. There have been art of many different tenors and temperaments, including the ones that often grow out of the flux of the society contesting the old aesthetic premise with the new ones. However there has been little or no effort – be that through institutional or individual intervention – to ferry these to the public realm with the conceptual or discursive underpinnings stressed, only to ensure that the viewers be inspired to develop a critical understanding of what they see. Quamrul, the epitome of Bengali artist who has always remained aware of the sociopolitical exigencies of his time, though regularly lionised by a section of the cognoscenti who seems to identify with his causes, little efforts have been directed towards the re-appraisal of his art. It is disheartening that no retrospective treatment has yet been considered around his life's work, and the fact remains that he is one of the most celebrated artists of the region, a public figure of the country. It is safe to deduce that those who (artists) plotted a different route in a slowly changing cultural-economic climate in the first few years following independence, received some sort of life-sustaining support from a minority made up of the connoisseurs from the rich segment of the society and a retinue of art lovers from the educated middle class. Over the last two decades, the tide has turned a bit in favour of art that conjugates the aesthetical with the social-political, perhaps per courtesy of the New Money being poured into art scene, apparently due to a boom in the apparel sector. Yet, in the absence of proper framework and coordinated institutional support, it is the individual talents with his/her ability to get on through the barriers, who actually have been playing the most decisive role, both as artist and as the arbiter of taste, or change in taste. Since independence the art scene has developed in the most unstructured fashion. The germination of artistic language that toppled some of the established notions the first generation artists, who emerged in the late 1950s, was made possible only due to the fact that some artists have chosen not to conform to norms. But their emergence has not been registered fully, wholeheartedly, as we are unable to drop the prejudices of the previous eras we often lug around, thereby affecting the sequence of growth.

It is difficult to define the new generation of artists with a few qualitative phrases, as throughout the 1980s and 1990s, many a creative exponent began to infiltrate the art scene with innovative ideas and processes. Among the artists who have contributed to the change that has occurred over the last two decades, Shahabuddin Ahmed also figures prominently, though he started out in early 1970s only to reside at the apex of the surge in the figurative art that was underway via a group of younger generation artists in the 1980s. In fact he is the last painter-hero – a cultural icon whose appeal has even reached down to level of the masses. His role in the war of independence as a soldier-commander has, over the years, also helped secure a place in the public consciousness. Those who emerged after him either introduced the language of protest or politics, or appeared as mediators -- negotiating the emerging practices of the West with a sense of their own locus of operation, with the exception of some unique talents who – with their transgressive spirit – seemed to have redefined the very language of art. Therefore the divergent practices that are part of the yet to be recognised artistic trajectory, starting from the practices of the late 1980s, when the venue of the Asian Art Biennale organised by Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy served as an important portal to freight art to the public domain. The unconventional and the experimental in art first appeared in the scene through this government apparatus, and later some of the bold and unrestrained minds taken that a lot further. Among such young exponents, Mabubur Rahamn, Ronni Ahmmed, Tyeba Begum Lipi stand for art that interrogates the standard processes through either a politically charged language, or simply by putting norm on its head; and Dilara Begum Jolly, Wakilur Rahman, Ahmed Nazir, Fokhrul Islam, Salahuddin Ahmed, Nasima Haq Mitu, Atiqul Islam and A Rahman afford a negotiation between established conceit and unconventional methods to transmit the new. If one looks at the mainstream art practices that are less concerned with the goings on in the pockets that are created by those who stage the 'difference' and gradually encroachment on the mainstream platforms, one will notice that the changes, though slow, take place through and due to the coexistence of contesting ideas. For example, the impact of Monirul Islam, who re-emerged in the Dhaka scene in the later part of the 1980s after a long interval, changed the perception of surface painting in this clime. Resident in Spain since the late 1960s, Monir has redefined abstraction and now boasts a retinue of followers. Among other artists who emerged in the 1970s, one of the most versatile is Kali Das Karmakar, whose complex yet charming visual solutions, mostly transferred into etchings, helped secure his reputation as an artist with the ability to overwrite the art of the past. As for going against the grain, or sowing the seed of discontent in the very tapestry of our mainstream knowledge and culture, Kali Das's performances are some of the earliest examples of body-oriented action in this region. The art scene that has witnessed the flowering of many talents of divergent tendencies in the last three decades also produced some regional star artists – among them are Shishir Bhattacharjee, Nisar Hossain, Dhali Al Mamoon, known for their political imagery that helped define the voice of pretest in the 1980s. Though now in self-exile, G S Kabir, another from the star constellation of the -80s, is now resident in Japan, who is known primarily for his early experimentations that challenged academic norms and regulations; and lastly, Mohammad Iqbal, whose depiction of mendicants shot him to fame in the late 1980s. And if we really want to look at the future, there is a whole bunch of young experimentalists who care little for culture-specificity or norms, or even the usual insurgent position, among these are painter and video artist Rafiqul Islam Shuvo, performance artist Abu Naser Robii, multimedia artist Promotesh Das Pulak, et al. Harking back to the issue of Quamrul Hassan and how we place him in the cultural landscape: To figure out a way to acknowledge the contribution of a major artist demands, at least, some form of organised, coordinated efforts, which we have not been able to muster. 40 years have elapsed since independence, yet the horizon of taste and sensibilities, which stretches over to every other domain such as film, literature, economics and politics, provides a foggy picture for even the most myopic. Yet we all know that there has been a boom in the arts. Contemporary art has broken some new grounds and the impetus came primarily from the private institutions and some enterprising individuals. Yet we want to be sure that our emerging artists attain the utmost and not fall into oblivion as it is 'doing' that should appear in our national register not the 'doer', as is the case with Quamrul. Textiles

Reviving Ancient Traditions The art of weaving is one of the most ancient traditions that has existed since the beginning of civilisation. Handloom products and handicrafts have been a part of the Bangladeshi culture for centuries. Craftsmen have passed on their skills and knowledge from one generation to the next and it is this tradition that makes handmade items so coveted and exclusive. Bangladeshi crafts people have been renowned for the intricacy and artistry, which remains unparalleled and unique to this day. According to the Bangladesh Hand Loom Board, there are about one million weavers, dyers, hand spinners, embroiderers and artisans in Bangladesh. These artistes use 300,000 looms and produce 620 million metres of fabric every year. This makes up 63 percent of the total fabric production in the country designed for local consumption and meets 40 percent of the local demand for fabrics. This industry also provides employment to about one million people in rural areas, most of whom are women. About half a million people are also indirectly employed by this sector, which contributes about ten billion takas yearly to the national exchequer as value addition. One of the most well-known and desirable handloom fabrics produced in this country is the Jamdani, a version of the famous Dhaka Muslin or Mul-mul. Dhaka has been well known for over ten centuries because of this inimitable fabric, a material so fine and delicate that it has been said that it is woven with the “thread of the winds.” Made on the loom with the finest cotton or silk yarn, this fabric bears exquisitely intricate designs embroidered or inlaid with gold, silver and silk threads. The Jamdani has been mentioned in Greek and Roman texts as one of the most coveted luxury items in the world.

The Rajshahi silk is another finely woven material-- soft and delicate silks that come in a variety of colourful shades, bold in their ethnic designs, which can be seen on the striking tough fabrics created by the tribal races from Sylhet, Cox's Bazaar and Rangamati. The saris made in Dhaka, Tangail, Nobabgonj and Pabna, the Khadi/Khaddar products from Comilla, the Manipuri blankets from Sylhet, fabrics with intricate zari work known as brocade made in the Mirpur area in Dhaka, are also famous for their quality and beauty. Lungi, gamcha, printed bed covers, pillow covers, tablemats, hand and kitchen towels, curtains, upholstery and furnishing fabrics are also produced in this industry. Apart from the traditional handloom fabrics, Bangladesh also produces a new kind of cotton fabric, supplied by Grameen Bank, a non-government, rural oriented financial institution which named their product Grameen Check. Grameen Bank realised that most weavers who produced handloom fabrics in rural areas were unemployed due to stiff competition from machine-made products. Many of these weavers borrowed money from Grameen Bank and were moving away from their craft. When Grameen discovered that Bangladesh spent about $ 80 million on imported fabric for their garments industry, they decided to play the role of supplier, hire weavers and started taking orders from the garment industry. They also ensured quality control and time management. The Grameen Check is now popular all over the country, in several European markets promoted by designer Bibi Russel, and has the potential, to penetrate other markets around the world. Another novelty in the textile industry has been the revival of the use of natural dyes. This age-old practice had become almost extinct due to the introduction of artificial dyes in the market, which were faster, easier and cheaper to produce. However, in 1986, a remarkable woman known as Ruby Ghuznavi, who is now the Chairperson of the Natural Dye Programme of the World Crafts Council, rediscovered the use of natural dyes. Guided by her mentors she did extensive research with a team of experts and discovered 30 colour fast dyes, which singly, or combined can provide a wide range of colours, both bright and subdued. Ghuznavi started a brand known Aranya Crafts and through this, introduced natural dyes into a niche market. Although not feasible for mass marketing, due to the lack of adequate raw materials and funding, these dyes are ideal for medium to small scale production and are popular due to their environmentally friendly nature. Following her example, many local brands have started using natural dyes, but Aranya's products stand unique due to their sole use of these dyes. It has been 20 years since Aranya was established, and it has trained and employed hundreds of craftspeople across Bangladesh, and organised and conducted a number of workshops in natural dyeing techniques in the UK, India, Pakistan, Turkey, Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Nepal. The beauty in the handloom crafts of Bangladesh is that they can evolve with the changing times and fashions. The traditional Jamdanis now bear more modern geometrical patterns and designs; the silks are produced in bolder colours and patterns and are used to make tops and shalwar kameezes for the current generation. The Grameen Checks are used to make everything from saris and fatuas to shirts and dresses. The key is to keep the crafts alive by nurturing them and encouraging their development into something new. Performing Arts

The Soul Food of Bengalis

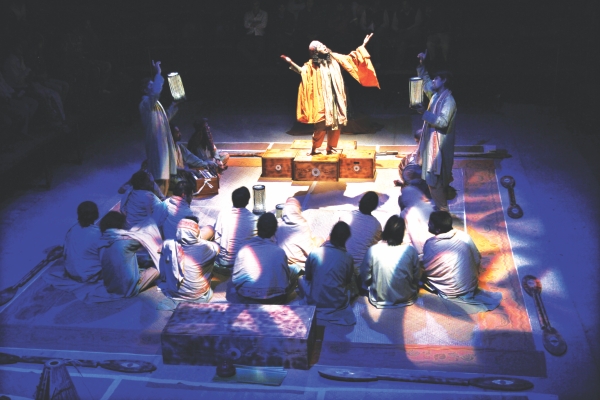

Performing arts have been an integral part of Bengali culture and characteristics. Like the whips of the Persians or Moghuls, the canons of the British or the Pakistani tanks, Bengalis have always resorted to the weapons of music, dance and drama to resist oppression. In a free land today, talented Bangladeshis are constantly experimenting in the different branches of performing arts, adding more and more genres to their already rich culture and heritage. After Liberation, the wave of rock music — a practice of constantly changing practices and styles of making music, not often following grammar and involving modern instruments— hit Bangladesh. Pop-guru and freedom fighter Azam Khan, along with Fakir Alamgir, Pilu Mamtaz, Ferdous Wahid, Firoze Shai introduced the pop-rock culture, presenting audience with simple and straightforward lyrics. The country witnessed the development of Bangla band music with Uccharon and Zinga Shilpi Goshthi setting the trend. Towards the beginning of the millennium more genres followed — metal, hard rock, alternative rock and folk fusion — saving Bengali listeners from the infiltration of Hindi film songs. Folk fusion brought the songs of the fields of Bangladesh to the urban youth familiarising them to their roots. Although this kind of music often attracts criticism from the more puritan quarters, it has nevertheless kept Bangla music alive. The evolution of these new genres of Bangla music has also contributed to the development of a thriving a music industry in Bangladesh.

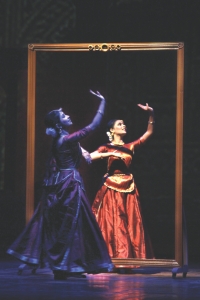

Compared to other forms of art, dance in Bangladesh has made slower progress in the last 40 years. A notable change is the stress given on classical form of dance. This trend began in the 80s after many dancers returned from India with training from classical dance gurus. Besides, Bulbul Lalita Kala Academy that started in the 50s, dance schools solely dedicated to particular genres of classical dance — Kathak, Bharatanatyam, Manipuri, Odissi — began to evolve. Today's dancers are experimenting with different forms of dance creating East and West fusions. Dance-dramas have also gained popularity in recent years. Leaving their weapons aside, some young freedom fighters took up guitars, while others focused on creating a theatre movement in Bangladesh. The year 1972 saw the emergence of Aranyak Natya Dal and the Dhaka University based theatre troupe Natyachakra. Nagorik Natya Sampradya, formed in 1968, became the pioneer of staging shows selling tickets in the 70s. The TSC auditorium at Dhaka University, Engineer Institute and British Council auditorium became popular theatre venues in Dhaka, followed by Mahila Samity, which, in fact, turned Bailey Road into a theatre street. Theatre'73, started in 1973 in Chittagong, led the way for more troupes in the city including Tirjak, Ganyam and Arindam. The most significant contribution to our theatre movement has been made by one of the pioneers of the Neo-Theatre movement and founder of Dhaka Theatre, Salim Al Deen. He incorporated the performance of traditional art forms into Bengali plays. He also developed a theatre terminology based on indigenous art forms, titled Bangla Natyakosh. The theatre movement reached out to the rural population in the 80s and collected indigenous art forms in theatre through the activities of the Gram Theatre and Mukta Natak. The practice of street plays also began in the 80s, giving birth to “rough plays” by SM Solaiman. Although theatre practice in Bangladesh is still at amateur level, theatre personalities have made their mark in the international arena. Veteran actor Ramendu Majumdar has been elected as the president of International Theatre Institute (ITI) worldwide for two consecutive terms. Bangabandhu Trial Justice Served

In the wee hours of August 15, 1975, a gang of disgruntled, blood-thirsty officers of the army murdered the Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman along with almost all members of his family. In another dark chapter of the country's history, Gen Ziaur Rahman, who usurped power in a bloody coup, promulgated the infamous Indemnity Ordinance, according to which the killers of innocent men, women and children were allowed to go scot free. The subsequent governments that assumed power, especially that of deposed Gen HM Ershad's regime, allowed the killers to do politics in the country. Ershad had even made one of the self-confessed killers of Mujib the Leader of the Opposition in his pet parliament. They were awarded with lucrative jobs in the foreign service. A precedent, dangerous and shameful that is, was set, according to which killers of women and children could not be even brought to justice. It all changed after the Awami League won the general elections in 1996, forming the government with some small political parties. The Indemnity Ordinance was scrapped, and some of the killers were arrested. Death penalty was handed down to Bangabandhu's killers, but before it was carried out, the AL had lost the 2001 general elections to the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, which, after coming to power, dilly-dallied the process of executing the Supreme Court verdict. After the AL was returned to power for the second time since the restoration of democracy, justice was finally handed down to Bangabandhu's killers, and the nation took a giant step in the direction of establishing justice and rule of law. BRAC The World's Largest Known formerly as the Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee and then as the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee, BRAC, which is based in Bangladesh, is the largest NGO in the world. Established by Sir Fazle Hasan Abed in 1972 soon after the independence of Bangladesh, BRAC currently has its centres in all 64 districts of Bangladesh, with over 7 million microfinance group members, 37,500 non-formal primary schools and more than 70,000 health volunteers. BRAC employs over 120,000 people, the majority of whom are women. BRAC operates programmes such as those in microfinance and education in nine countries across Asia and Africa, reaching more than 110 million people. The organisation is eighty percent self-funded through a number of commercial enterprises that include a dairy and food project and a chain of retail handicraft stores called 'Aarong'. BRAC maintains offices in 14 countries throughout the world. The most commendable side of BRAC is its focus on women empowerment. Among their numerous praiseworthy efforts, BRAC's centres for adolescents called Kishori Kendra provides reading materials and serves as a gathering place for adolescents where they are educated about issues sensitive to the Bangladeshi society. In 1996, BRAC started a programme in collaboration with the Ain O Shalish Kendra (ASK) and Bangladesh National Women Leader's Association (BNWLA) to empower women to protect themselves from social discrimination and exploitation and to encourage and assist them to take action when their rights are violated. BRAC also offers external services such as access to lawyers or the police either through legal aid clinics, by helping women report cases at the local police station or when seeking medical care in the case of acid victims. BRAC works on a range of issues, including education, health, agriculture and food security, social and legal services and community empowerment. It is a shining example of the country's progress and efforts to be better and rather self- reliant as opposed to Bangladesh's trademark as a country in debt and in need of external support. Judiciary Hoping for a separation Shakhawat Liton

The principle of judicial independence rests on the idea of separation of governmental powers: executive, legislative and judicial. Bangladesh's Constitution, which came into force on December 16, 1972 upholds the principle of separation of the state power by announcing it as one of the fundamental principles of state policy. The Constitution in article 22 puts on the state the responsibility to ensure separation of the judiciary from executive organs of the state. Maintaining conformity with that fundamental principle, the original article 116 of the 1972 constitution vested the control of the lower judiciary in the Supreme Court. It was the Supreme Court that had the control including the power of postings, promotions and granting of leaves, and of disciplining the persons employed in judicial service, and the magistrates exercising judicial functions. The Supreme Court also had a major role to play regarding appointments to the lower judiciary as the article 115 of the original 1972 constitution stipulated that district judges would be appointed by the president on recommendation from the Supreme Court, and all other civil judges and magistrates exercising judicial functions would be appointed by the president in accordance with the rules made by himself or herself in consultation with the Public Service Commission and the Supreme Court. Things were moving in the right direction in the newly born country with its Constitution outlining the powers of three branches of the state. But the Constitution's fourth amendment passed in 1975 upset the entire outline over the separation of the state power. The nefarious amendment brought drastic changes to articles 115 and 116, pushing the matter in the opposite direction. It vested the control over the lower judiciary in the president who was also empowered to make the appointments, in effect allowing the executive branch to control the lower judiciary. Later, a martial law regime led by Ziaur Rahman in 1978 amended the constitution through a martial law proclamation inserting a new phrase in article 116 that returned to the Supreme Court some little power regarding control and discipline of the lower judiciary. But it did not improve the situation. And since then none of the successive governments took steps to separate judiciary from the executive in light of the fundamental principle of state policy. Things, however, started taking a different shape when the High Court on May 7 of 1997, in response to a writ petition, delivered a historic verdict with 12 point directives to ensure separation of judiciary. But the then government refused to implement the court's directives and preferred to file appeal against it. In disposing of the appeal, the Appellate Division on December 2 of 1999 delivered its order bringing some modification to the HC verdict. But the successive governments since then took extension of times to complete the necessary tasks in line with the court's directives to ensure separation of judiciary. Finally, the military backed Caretaker Government took a positive stance. The lower judiciary was officially separated from the executive branch on November 1, 2007 following the Appellate Division's directives. Laws were amended and new rules were framed for that purpose as well. However, the constitution was not amended to ensure effective separation. As a result the executive branch still controls postings and promotions of judicial officials, albeit "in consultation with the Supreme Court". In its verdict on the constitution's fifth amendment case, the Appellate Division has rightly said: "Independence of the judiciary, which is one of the basic features of the constitution, will not be fully achieved unless the articles [115 and 116] are restored to their original position." The two articles were not restored to their original position in the latest constitutional amendment, leaving the hope for an effective separation of the judiciary in a state of uncertainty. Now the government should reassess its political stance over the separation of judiciary and should come forward with liberal mind. The partisan government should keep it in mind that judicial independence is an important value in any democratic system of government and without ensuring this independence no government can claim itself democratic. The writer is Senior Reporter, The Daily Star.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |