| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 04| January 27, 2012 | |

|

|

History When Textbooks Lie Naimul Karim “After the 1965 war India conspired with the Hindus of Bengal and succeeded in spreading hate among the Bengalis about West Pakistan and finally in December 71, caused the break-up of East and West Pakistan.”

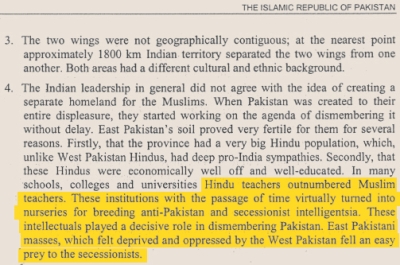

The above words have been taken from a Pakistani social sciences textbook meant for students of class 5. While the core reasons behind the fight for an independent nation, during the liberation war of 1971, may be clear to the present generation of Bangladeshis, the Pakistani youth of today are being taught a 'different' page of history, a fact that several Pakistani writers and independent organisations have protested against. A research paper, entitled 'Curriculum of Hate', published by the Centre for Research and Security Studies (CRSS), an organisation founded by the civil society activists of Pakistan, claims that the National Education Policy of Pakistan 'does not teach but preach'. It further states that the school curricula continue to 'sermonise hate, prejudice intolerance and breed extremism.” The condition of the education system can perhaps best be understood by a passage, related to the war of 1971, from a social sciences textbook for students of class 9 and 10, published by the paper. It states, “The education sector in East Pakistan was totally under the control of Hindus. Under the guidance of India they fully poisoned the minds of Bangalis against Pakistan and aroused their sentiments.” More recently, an article published in a Pakistani daily entitled 'The Fall of Pakistan', claims that national textbooks have cited the dominance of Hindu teachers, international conspiracies and economic battles as the main reasons behind the protests of the East Pakistanis. Furthermore, it claims that none of the textbooks under the public education board mentions the 'atrocities committed by the Pakistani army– which includes rapes, targeted killings—against the Mukti Bahini and the genocide of the Bengali population.' According to Usman Qazi, an independent analyst from Pakistan, the education policy has been similar to the country's foreign policy– anti-Indian. “The main ideological thrust has been that the Hindus never accepted the distinct existence of the Muslims in the sub-continent and have perpetually been conspiring against them,” explains Qazi. He further says that ever since the separation, the military-dominated establishment has ensured no meaningful analysis of the events that took place before and after the war.

Like Qazi, several other Pakistanis blame the army for manipulating the National Education Board. An article entitled 'Glorification of War and the Military' published by the Sustainable Policy Development Institute of Pakistan (SDPI), an independent organisation, states that the interests of the military have been promoted in society through the educational system. The materials in the textbooks, according to the SDPI, create hatred and form 'enemy images'. They have also been accused of 'glorifying wars'. Another article from the same paper states that students in Pakistan don't learn history; they are rather 'forced to read a carefully crafted collection of falsehoods, fairy tales and plain lies.' Passages taken from educational textbooks, in the same article, indicate the fabricated form of history that students are taught. One such passage states the following: “In 1971 while Pakistan was facing political difficulties in East Pakistan, India helped anti-Pakistan elements and later on attacked Pakistan. As a result of this war in December 1971, the eastern wing of Pakistan separated and appeared as Bangladesh on the world map.” Although teachers, writers and independent organisations strive to bring a change in the education system, they face stiff challenges from the national authorities. One such example comes from Mehnaz Akhtar, a part-time economics professor, who used to take classes at a military-run university. In one such class, related to the economy of Pakistan, she criticised the role of military in the national-political economy and referenced to their role in the former East-Pakistan. Thereafter, she was warned by the authorities. Akhtar never went back to the university. Perhaps the most recent criticism of the Pakistani administration came from cricketer-turned-politician, Imran Khan when he related the government's treatment of Pashtuns to the East-Pakistanis in 1971. A magazine that published an interview of the former cricketer quoted him saying, “If the Pakistanis who committed crimes during the Liberation War of Bangladesh had been punished, the present scenario in Pakistan would have been different.” The burning question, however, is whether the majority of the Pakistani population believes in the stories narrated to them through these textbooks. A number of newspaper articles published with respect to this issue suggests that over the last decade there has been a shift in the school of thought. Echoing similar sentiments, Qazi says that the present day perception of the events of 1971 varies among the people of the four provinces of Pakistan. “I think that it is safe to state that bulk of the three smaller provinces do not at all subscribe to the establishment's version of history. A section of the population of Punjab and some people in Urdu speaking population of urban Sindh may still believe the Indian conspiracy theory,” he says. He further said that with the proliferation of mass media and increase in general literacy, a lot of alternate versions of history have come forth. “But these are still on the margin of the official rhetoric, in my view,” says Qazi. Forty years have passed by since the bloody war. One would find it appalling to know that doubts regarding the story of the birth of Bangladesh still linger in the minds of several Pakistanis. Perhaps what's even more appalling is the fact that the United Nations doesn't recognise the atrocities committed in 1971 as genocide, despite overwhelming evidence. One would hope that the government of Bangladesh manages to complete their 'age-old dream' of digitising the war-documents and release them to the public and the world in general, before the story is lost forever. Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |