| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 20| May 18, 2012 | |

|

|

In Retrospect Calcutta during World War II S A Mansoor

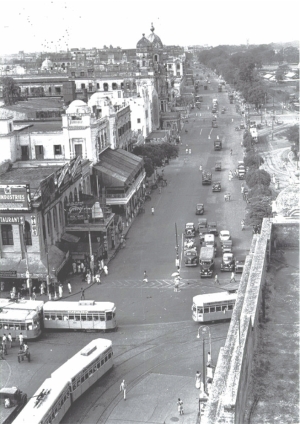

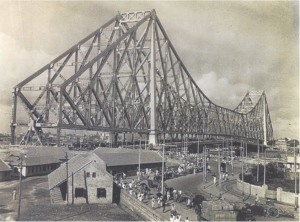

It was the early 1940s, during the last World War. The allied forces were retreating after relentless attacks across Burma from the advancing Japanese army. The eastern war front was very close to Dimapur, a rail-head town close to the Burma border in the eastern-most Indian province of Nagaland, of the then British India. The easy and relaxing life of peace time Calcutta, where we then lived, was gone. It was wartime days, and all the materials of daily living, including basic food items, were scarce. Everything from rice, wheat, sugar, bread cooking oil, petrol and even municipal water supply was scarce and rationed. Long queues from early morning to collect drinking water from public water taps were a common sight in the streets of Calcutta. So were the long queues in front of each and every food ration shop for the purchase of much needed essentials. Going to school across Wellesly Street, usually a ten minute walk from our house, sometimes took over half and hour, as large convoys of heavy ten-wheeled American trucks that we saw for the first time, carrying military troops and supplies, drove down the street at a slow speed. The street could only be crossed when such convoys had passed. In the evening, strict blackouts were observed; there were no street lights, with Air Raid Precautionary (ARP) teams patrolling the roads and lanes to ensure that not a glimmer of light was visible from outside. Everyone had to be home before sundown, and all offices and business houses had to follow the daylight savings working time from 8 am to 4 pm. After sunset, only the petty thieves and pick-pockets plied their trade in the secrecy of darkness. Schools closed by 3.30 pm and for us children, the only relaxation was playing football or walking round Wellesly Square in the late afternoons, which was less than 100 yards from our house. However, we were strictly ordered by our parents and elders to return before sundown. The air raid shelters, and random baffle walls, built in the square, were popular hideouts for when we played hide and seek. However, after dusk, the park became a notorious place for illicit rendez-vous between questionable Indian and Anglo-Indian women and the overseas troops based in Calcutta. Quite often, large ten-wheeler army trucks used to park in front of our house, possibly calling on the couple of Anglo-Indian families, who were our neighbours. The only male person in our house was yours truly, under ten years of age. Later my uncle, aunt and their children also stayed with us, having escaped from Burma, leaving behind their decade-old timber plantation in central Burma, near Mandalay, and furniture manufacturing factory and retail furniture shop at Rangoon. They travelled by trucks, carts, and crossed rivers by boats and all sorts of other transports – luckily, always some miles ahead of the advancing Japanese troops. Ultimately they reached Dimapur at that time a part of Assam, and from there they took the train to Calcutta. They came literally with only the clothes they wore, plus a few hand bags that they could carry themselves. Fortunately, they could bring with them some valuable precious stones from Burma, which helped them to get start-up capital in Calcutta. Being an experienced businessman, my uncle managed to set up a chemist shop in Lindsay Street adjacent to the Calcutta New Market, a landmark shopping centre, and established himself in the business. During this time, the new Howrah Bridge was nearing completion, connecting Calcutta, the financial centre of India, with Howrah railway station, across the Hoogly River. The railway terminus connected Calcutta to the vast hinterland of North and South India. The feature of this new bridge was that it had tramlines, connecting the Calcutta tramway system with the Howrah tramway system, which was isolated earlier. The magnificent new bridge was opened to traffic, during war time, and taking a tram ride across the new bridge was a popular Sunday morning outing. On a Sunday morning after breakfast, my uncle took all the children for a tram trip across Howrah Bridge. My sister, I and his daughter and two sons, all of us being within two to five years age of each other in age, were in the touring party, while uncle was our tour leader. Taking a tram from Wellesly Street, we changed trams at Esplanade, on our tram ride over Howrah Bridge. However, the sudden shrill sound of air raid sirens right when we were approaching the bridge from the eastern bank stopped the tramcar, as the overhead electric cable power of tramways was switched off for air raid safety. We scrambled off the tramcar, and went down at least fifty or more steps to a small mosque for shelter. There was nothing but warehouses and offices on the street above, closed on Sunday. The mosque was close to the river bank, and located not far from the huge main bridge foundation on the left bank of the river. From the mosque, we had a clear view of the ships at Kidderpore docks, about a mile away downstream. It was around 10 in the morning, when the Japanese planes started diving and dropping bombs on the ships, which was visible from the mosque, the only place where we could take shelter. The explosion of bombs and the rattle of the anti-aircraft gun fire, along with the sound of the planes diving, created a cacophony of loud and frightening noise. Peering from the mosque window, it appeared that the planes were coming straight for us; but actually they were rapidly climbing, to avoid the floating balloon barrage of thick steel cables protecting the new Howrah Bridge. One huge explosion was the most fearsome; it was followed by a huge fireball with more secondary explosions and fires, and thick black smoke covered the dock area. Later we came to know that it was a direct hit on an ammunition laden ship, which was being unloaded when the air raid started. The memory of the fearful day – something that happened over 70 years back – is still etched on my memory. The raid lasted for half an hour at most; but to us it seemed like an eternity. When the all clear siren was sounded, we came up to the road, and took the next tram back home. All thoughts of crossing the Howrah bridge by tram, had evaporated. My mother and aunt were overjoyed when we reached home, and we enjoyed a long lunch, reliving our experiences. The writer is a retired engineer.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |