| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 26| June 29, 2012 | |

|

|

Musings Rediscovering Bangabandhu . . . Syed Badrul Ahsan

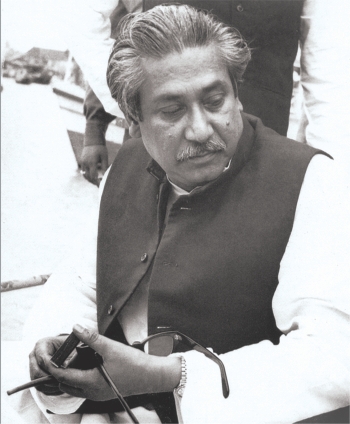

Bangabandhu should have lived longer. But, then again, we did not permit him to live beyond three and a half years into freedom. He was a mere fifty five when he was assassinated and none of us in this country had the courage to stream out on to the streets and send his murderers packing. Today, no matter how much we mourn his passing, no matter how much we condemn the conspirators who did him in, the reality is that when he fell on 15 August 1975, all of us stayed at home. No one raised the question of why he had been killed. The man who had struggled all his life for us, for the attainment of our liberty, lay dead on the stairs of his home, along with his family. And we pretended that things would get back to normal. There were many who even deluded themselves into thinking that since Khondokar Moshtaque had taken over, everything would be all right. They did not want to know that this was the man who had been behind it all.

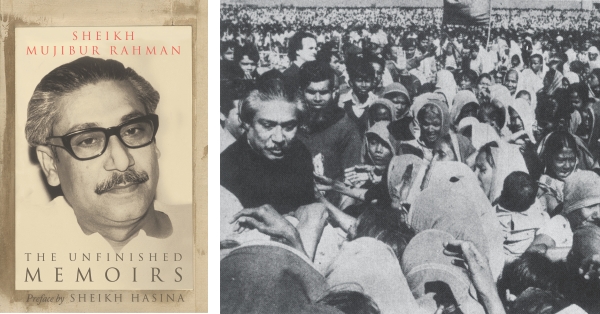

Today, as we read through Bangabandhu's Unfinished Memoirs (just out from the University Press Limited), we remember once again the full-blooded politician, the man of substance Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was and continues to be all these decades after his death. These memoirs are but a reflection of the man in all his potency of political intelligence. They are not memoirs in that full sense of the meaning, seeing that they come to a stop in the year 1955. And, as we have been told, he wrote them during his rather long spell in prison between 1966 and 1969. Those were formative years for Mujib, decisive for the people of Bangladesh. Taken into custody by the Pakistan government under the Defence of Pakistan Rules in May 1966, Bangabandhu (he was yet to be accorded that coveted position by a grateful people) found himself, in early 1968, the target of the Ayub Khan regime's overwhelming wrath. The people of East and West Pakistan were informed, in a huge demonstration of arrogance, that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had been conspiring to lead Pakistan's eastern province to independence as a free state. Consider the psychological trauma the Bengali leader must have been in at the time. Here he was, face to face with the biggest crisis of his career, one that certainly promised an end to his life through execution. And yet, as we now know, he was busy writing away, recalling all the little details of the life he had lived since he was born in March 1920. You can be sure that Bangabandhu meant to finish his memoirs. The style and tenor of the writing in the Unfinished Memoirs demonstrate writing skills which are evocative of his oratory. It was simple and yet it was profound. The memoirs are an instance of a politician to whom only his people mattered. Nothing else did. He speaks of his boyhood, of the conviction with which he threw himself into the struggle for Pakistan. His respect for Mohammad Ali Jinnah never wavers, despite the latter's blunder over the language question. There are others for whom he feels clear contempt, Liaquat Ali Khan for example. He writes with feeling about the impoverished and the deprived. He talks of rivers and songs sung on a boat, of the placidity of the waves. You read the work and you wish Bangabandhu had gone on to finish the memoirs. But, then, he did not have the time and the opportunity to go on. The struggle for the Six Points, the need to win the general elections in 1970, the conspiracy hatched by Yahya Khan and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto sliced away at his time. At a point when absolute leadership was called for, Mujib could not afford to give himself over to writing. And so the memoirs came to a halt, never to be picked up again. Perhaps Bangabandhu could have resumed writing in the nine months he spent in incarceration in Pakistan in 1971? But that spell in prison was, for him and for the Bengali nation, most horrendous and worrying. We did not know where he was. He had no access to books and newspapers, to pen and paper. Radio and television were not to be given to him. For nine months the Pakistan army killed our people; for nine months we waged war for freedom. And yet Bangabandhu was not permitted to know what was happening in the world outside his prison cell. Would Bangabandhu have completed the memoirs had he lived beyond 1975, beyond power? We will never know. We did not let him live. The realisation that he was no more began to dawn on us rather late in the day. It took us twenty one years to have the process of justice for his murder get under way. It took us another thirteen years to have some of his assassins walk the gallows. We rediscover Bangaba-ndhu through his Unfinished Memoirs. There was a poetic soul in him, a humanist who entered politics on the strength of his religious attachment to the idea of Pakistan and yet who soared one day, away from communal politics and into a higher calling we now know as Bengali nationalism. The future is what the Unfinished Memoirs point to. In Sheikh Mujibur Rahman there was a leader in the making. The Unfinished Memoirs give us a writer. Despite our shame at not running his murderers out of town on the dawn they killed him, we are proud, cheerfully hubristic, in knowing that Bangabandhu was, is and will always be our claim on history. The writer is Executive Editor, The Daily Star.

|

||||

|