| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 37| September 21, 2012 | |

|

|

Trevel

In Ink, On Silk Andrew Eagle

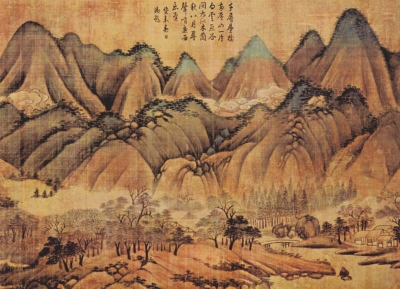

To state that the artist takes inspiration from the landscape is to say nothing in the way that stating the obvious is nothing. But could there be a landscape that takes its inspiration from artists? If there was such a place, it might be the countryside along the Lí Jiâng, the Li River in China. In the sixth century, art critic and writer Xiè Hè documented his six principles of Chinese painting in the preface to his book 'The Record of the Classification of Old Painters.' The first principle, 'spirit resonance' refers to the flow of energy that encompasses theme, work and artist. Without it, Xiè Hè remarked, there was no need to consider a work further. It's a house of camel hump hills, the banks of the Li, an arrangement of karst peaks and fog that's become renowned. The water currents flow simply, with steadiness, and the mist of cloud and rain rises slowly to reveal the white and pinkish hues of the limestone faces of the mountains. There is sadness and mystery in their cliff expressions: perhaps they are images of old age.

And the theme? It's up to the viewer obviously, but might I suggest it's about eternity? It's worth considering if long ago histories and, like serving tea, the smallest traditions that have marked China's millennia, aren't on display in the mountainsides, caught up in the banded, uneven cliffs and rocks. The sadness might be the usual result of longevity; of change and reformation and change. The mystery might be of an eon, ritual and repetition variety where seeming stillness is in fact gradual evolution. The Li might be the very portrait of China? The spirit resonance is there, no doubt, and Xiè Hè would not dispute the need to further consider the Li.

From Guìlín to Yángshuò the tourists go, by boat they float along the Li. It's the critic's route to admire the work, a vista dabbed softly with a fog and stone admixture. It's more than pleasing to the eye. Each hill is unique, standing like an expert stroke of Chinese calligraphy, in ink on silk. It's about the texture. It's about the brush. Each hill is deceptively relaxed and straightforward as can only happen if it's been rehearsed a hundred times beforehand. Only then can it become so natural. The third principle of Xiè Hè is 'correspondence to the object' which relates to shape and line, the depicting of form. The Li has incorporated that challenge too, in the gentle unexpected curves, horizontally in the river's chosen path, its repose, and in the lazy temporal line of the tourist boat, as well as vertically in the ridges of the mountains that seem purposefully to bring to the sky no harsh outline. Only a master artist could have captured such gentleness, could have thought to capture such gentleness. 'Suitability to type' is principle four, concerning the application of colour, layers, value and tone. It's a mop of green brush hill-hair, the banded strips of cliff in grey and pink and the opaque darkening of the fade-to-distance-summits that the Li offers in response. Colour is in the modern faces in sunhats too, viewing the offering through a screen and talking in many languages. They come from many countries to admire the Li. Layers are found in the flattened smaller motor boats, historical, to be privately hired from one or other bank, and the tone is brought to life by the contrast between the red and yellow Chinese flag fluttering about the boat's back that screams 'here and now' and the hills beyond which again, make all human resolve appear small and impermanent. China was, is, will be: what the mountain-art might be saying. It's about an older China, an old woman and an old man, a civilisation that runs beyond the glare of Shanghai's neon.

'Division and planning' is Xiè Hè's penultimate principle, about composition, arrangement, space and depth. There's little to add to that, with each hill placed as though with astute deliberation in the formation, ink stroke by ink stroke, that in combination makes a character. The Li has not overlooked this aspect. Lastly, Xiè Hè considered 'transmission by copying,' a virtue which referred not only to real life but also from the works of antiquity. Copying means learning and appreciating in an art form where new and original were not the sole desired elements. It means being a part of bigger traditions. And here too it cannot be said that the Li disappoints, since as much as each hill is unique so the downstream has learnt from the upstream, like newer from older, and the treasures of antiquity there are, in the passage of the message of eternity, from Guìlín to Yángshuò by boat. As the boat pulls up beside the Yángshuò dock it's indisputable: with the Li, Xiè Hè could not but be pleased. |

||||||||||||||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |