| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 41| October 19, 2012 | |

|

|

Achievment A CENTRAL ASIAN JOURNEY NEEMAN SOBHAN

The high speed train from Tashkent, leaving at 9:30 a.m delivered us at Samarkand station in the late morning hours. Met by our Tourist guide, the well-informed and engaging Russian origin Samarkand born, Dennis, and the Muslim-Uzbek driver, we went to the hotel just to dump our luggage, and set out to discover Amir Temur's city. Dennis immediately put my narrow conception about Samarkand into perspective. “You know, I am sure, that the historic town of Samarkand is not one city, but different cities in different ages. Over the centuries or rather millennia, it was built, destroyed and rebuilt.” I am impressed with his English and his tactful way of providing us basic historical facts. As we weave through the modern city towards the blue domed medieval citadel of brochures, he speaks about ancient Samarkand evolving through various historic ages, always at the confluence of diverse civilisations, empires and conquerors; a cradle for different religions and cultures. He chatters on, while I thrill to be finally here on this lovely mid-morning in May, warm in the sun but cool in the shade, starting our time travel into a city whose multi-millennium history gave it the title of the Rome of the East. Dennis points to some brown hills and the remains of fortified walls. “That's Afrosiab, the ancient citadel. Yes, Samarkand first appeared as ancient Afrosiab in the 7th century B.C. as capital of the Sogdiana Empire. Of course, Samarkand's most glorious period was in the Temurid era, from the 14th to the 15th centuries. This was after it was destroyed by the Mongol invasion of Chenghis Khan in 1220. At that time, it was part of the Kingdom of Khwarezm. And before that it was ruled by Turkic peoples from the 11th century, and earlier by the Samanids of Iran from 9th to 10th centuries. And Islam, as you know, came before with the Arabs in 712.” By now we are passing Afrosiab and I ask if we can enter. Dennis shakes his head. “This area with the excavated remains of the fortified antique citadel and its palaces, residential and craft related quarters is presently not open to visitors. It is being preserved by UNESCO as an archaeological reserve. But you can take pictures from outside.”

Suddenly, to the south-west of Afrosiab, we glimpse turquoise tiled domes and minarets. We have jumped from the ancient to the medieval and are in the capital of the empire of Amir Temur or Tamerlane (1336-1405) which once extended from Central Asia to Persia, Afghanistan, and India.

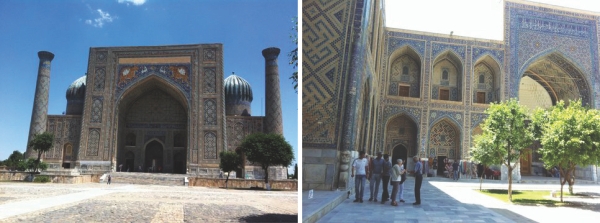

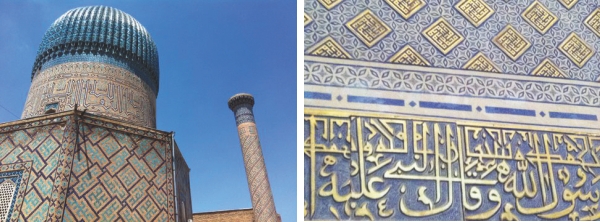

I had asked to see the major monuments of the Temurid period, and Dennis said he would show us over two days, first, the Gur-Emir (Temurid family mausoleum and mosque complex); the Bibi-Khanum Mosque; the Registan square with its Madrassahs and Mosques; the Observatory of Ulugh-Beg, Temur's illustrious and astronomically inclined grandson, and the Shahi-Zinda ensemble. The moment we set eyes on the Gur-Emir with the ribbed Mediterranean sea-blue and gold embroidered cap of a dome, the beige and blue minarets intricately engraved like a shawl, arched portals and facades with majolica tiles and mosaics, and the internal ceiling of the dome tooled in gold and lapis in geometric motifs and calligraphy, we stood stunned and dazzled by the intricate beauty of what was obviously seminal art forms that later influenced the Indian Mughal traditions. The workmanship and decorative skills of the Temurid artisans left us dumbstruck as we went from one gorgeous monument to the next. Each was more perfect in design and conception than the other. Madrasahs, mosques, Sufi khankas, courtyards, palaces, windows, doors, ceilings, roofs, mahrabs, walls, columns, all made us realize that we were standing at the source of what would nourish the art and architecture of the empires of a whole region, from the Safavids of Persia, the Mughals of India to the Ottomans in Turkey. We spent the whole day strolling mesmerized through monuments, with only a brief break at a Choikhana with fresh baked Somsa and tea to fortify us physically. Our hearts, minds and eyes were bursting with a surfeit of exquisitely crafted beauty. At the Bibi-Khanum Mosque built by one of Temur's senior wives, we sat in the courtyard garden with roses and a giant concrete Rahel or Quran stand. While resting on the marble steps we contemplated our next stop, the Registan square, before we went back to the hotel for rest and a private dinner at a home arranged by the Agency.

The Registan or 'Sandy place,' a sprawling paved square with magnificent domed structures flanking three sides was in Temur's and Ulugh Beg's time a centre of commercial, public and ceremonial activities. The original buildings were: a majestic Madrassah to the west with embellished arched portals which could accommodate 100 students in the rooms located on two floors; and opposite it a Sufi Khanka to the east, (later to be reconstructed as the Sherdor Madrassah with the unusual mosaic images of tigers); and a Caravansarai to the north (subsequently reconstructed and renamed by the gold plate work on facade as the Tillya-kari Madrassah). More next time! Since, the sights of Samarkand cannot be recounted within the confines of one column installment, I am draping Scheherazade's mantle to spin this tale over a second session, a fortnight away. NEXT: SAMARKAND OF ULUGH BEG

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||