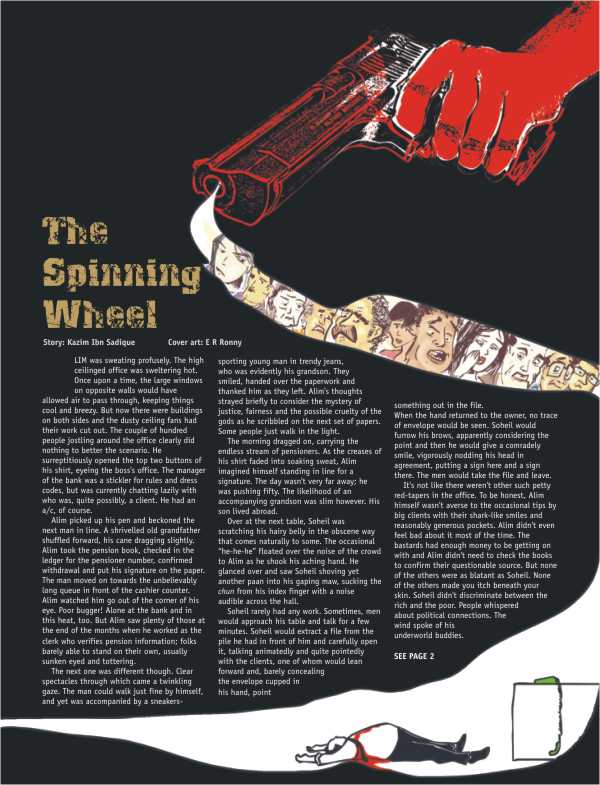

The Spinning Wheel

Story: Kazim Ibn Sadique

Cover art: E R Ronny

Alim was sweating profusely. The high ceilinged office was sweltering hot. Once upon a time, the large windows on opposite walls would have allowed air to pass through, keeping things cool and breezy. But now there were buildings on both sides and the dusty ceiling fans had their work cut out. The couple of hundred people jostling around the office clearly did nothing to better the scenario. He surreptitiously opened the top two buttons of his shirt, eyeing the boss's office. The manager of the bank was a stickler for rules and dress codes, but was currently chatting lazily with who was, quite possibly, a client. He had an a/c, of course.

Alim picked up his pen and beckoned the next man in line. A shrivelled old grandfather shuffled forward, his cane dragging slightly. Alim took the pension book, checked in the ledger for the pensioner number, confirmed withdrawal and put his signature on the paper. The man moved on towards the unbelievably long queue in front of the cashier counter. Alim watched him go out of the corner of his eye. Poor bugger! Alone at the bank and in this heat, too. But Alim saw plenty of those at the end of the months when he worked as the clerk who verifies pension information; folks barely able to stand on their own, usually sunken eyed and tottering.

The next one was different though. Clear spectacles through which came a twinkling gaze. The man could walk just fine by himself, and yet was accompanied by a sneakers-sporting young man in trendy jeans, who was evidently his grandson. They smiled, handed over the paperwork and thanked him as they left. Alim's thoughts strayed briefly to consider the mystery of justice, fairness and the possible cruelty of the gods as he scribbled on the next set of papers. Some people just walk in the light.

The morning dragged on, carrying the endless stream of pensioners. As the creases of his shirt faded into soaking sweat, Alim imagined himself standing in line for a signature. The day wasn't very far away; he was pushing fifty. The likelihood of an accompanying grandson was slim however. His son lived abroad.

Over at the next table, Soheil was scratching his hairy belly in the obscene way that comes naturally to some. The occasional “he-he-he” floated over the noise of the crowd to Alim as he shook his aching hand. He glanced over and saw Soheil shoving yet another paan into his gaping maw, sucking the chun from his index finger with a noise audible across the hall.

Soheil rarely had any work. Sometimes, men would approach his table and talk for a few minutes. Soheil would extract a file from the pile he had in front of him and carefully open it, talking animatedly and quite pointedly with the clients, one of whom would lean forward and, barely concealing the envelope cupped in his hand, point something out in the file. When the hand returned to the owner, no trace of envelope would be seen. Soheil would furrow his brows, apparently considering the point and then he would give a comradely smile, vigorously nodding his head in agreement, putting a sign here and a sign there. The men would take the file and leave.

It's not like there weren't other such petty red-tapers in the office. To be honest, Alim himself wasn't averse to the occasional tips by big clients with their shark-like smiles and reasonably generous pockets. Alim didn't even feel bad about it most of the time. The bastards had enough money to be getting on with and Alim didn't need to check the books to confirm their questionable source. But none of the others were as blatant as Soheil. None of the others made you itch beneath your skin. Soheil didn't discriminate between the rich and the poor. People whispered about political connections. The wind spoke of his underworld buddies.

The manager gave his table a wide berth when he was doing his rounds.

If Alim ever lost it, he prayed that he would have enough sense to jam a pen up Soheil's nose and give a sharp twist, scrambling his brains.

The work was getting on his nerves. Alim put down the pen and announced he was going to the toilet, to the audible grumbling of the folks in line. He felt a twinge of annoyance. He had been working since morning. What did they expect him to do? Hold off Nature?

He lit up a smoke in the bathroom and took a whizz, squinting against the smoke. No bathroom is ever completely quiet, what with the tinkle of water in the cubicles and glugging sound in the pipes. He finished his cigarette in the relative silence, the smell of it masking the inherent stink of a semi-public toilet, and walked out to a situation.

A doddering old-timer had strayed from Alim's empty desk to Soheil's and had demanded a signature so that he could collect the remnants of payment from a job he had retired from long ago. Soheil, being Soheil, had probably demanded some payment to his own self. The old man was incensed. A crowd was gathering and the manager was nowhere to be seen. A stickler for rules, but a coward when it came to sticky situations. Such is management.

“Where will I get money to pay you, you blood-sucker,” the old man's broken voice had risen over the fading commotion of the bank somehow. He pointed at his clothes with his shaky hands. His white punjabi was brown and there were small torn patches in his lungi. “Do you see this? Do I look like a person who has 500 taka?”

Soheil had apparently stopped listening at the name-call. “Blood-sucker? Who the hell do you think you are, old man? If you want the wheel to turn, you have to oil it. If you want your goddamn money, you got to pay up first. The world doesn't run by your word.”

The old man was almost catatonic in his rage. The embers of a long extinguished fire danced on his furious face as he stood up a little taller and his rheumy eyes became clear, maybe for the first time in a long time. The no-longer broken voice uttered a curse of eternal damnation and he raised his cane like a sword and brought it down on Soheil's shoulder. The effect was negligible and Soheil pushed the cane away, which took the old man down with it.

Just like that, the temporary window into the blazing past was gone. There was just an old man whimpering on the ground.

While people stared at the scene with morbid fascination, two people walked through the front door. Alim was still deciding whether he should finally introduce Soheil's nose with his pen, when the men pushed through the throng to Soheil's desk. Everything went into that curious slow motion that nature gifts to its children at those once-in-a-lifetime moments. Soheil's head turned to the men, just as they pulled out the guns. He screamed and Alim swore later that he could see spit fly. Gunshots thundered through the high hall, the screams were cut off. There was a moment of near-perfect silence, broken only by the faint trickle of blood. The men looked around and said, in a bid for the hall-of-fame of poetic justice, “For his sins.”

The men turned around and walked out, calmly tossing a few cocktails over their shoulders. There was a curiously bovine stampede as people tried to move away from the small explosions and the men, while at the same time, trying to get away from the murder scene. Alim managed to carry the old man out, and while he stood waiting for the panicked masses to make it through the door, he once again pondered on mystery and justice. He thought about gangsters and mob-hits. And he thought of deus-ex machina.