Cover Story

Exhuming the Truth

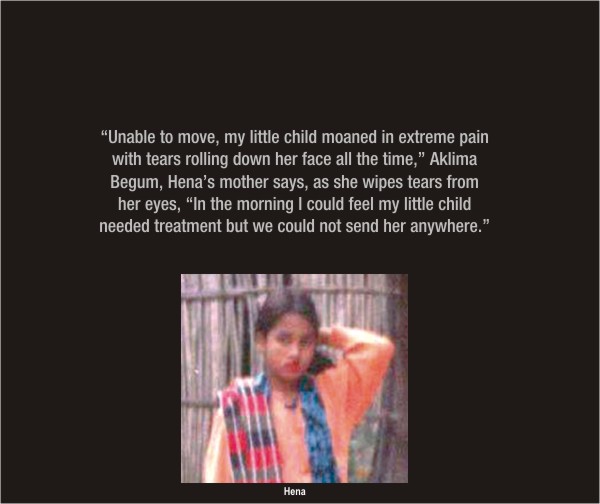

Fifteen-year-old Hena was raped and tortured by her rapist's relatives in a remote village in Shariatpur. A village tribunal imposed an edict to lash her 101 times for her 'crime'. Unable to bear the brutality, Hena succumbed to her injuries. The first autopsy report however, stated that there were no injury marks on Hena, completely denying the barbaric treatment meted out to her. A new court ruling, however, ordered for her body to be exhumed. A second autopsy has given clear evidence of the heinous crime committed against her.

Morshed Ali Khan and Emran Hossain

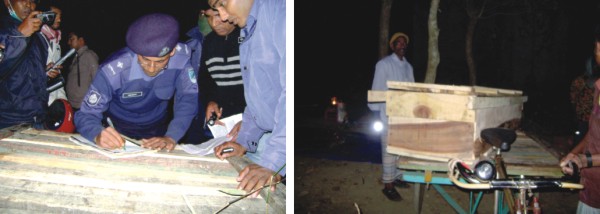

Nurul Islam has been a dome (a traditional morgue assistant) for the last 18 years working in the dirty corridors of Shariatpur's state-run hospital morgue. Today he is nervous. In his long experience he has never before exhumed a human body from the grave in the dark of the night. That too, without electricity and in a remote village called Chamta, 30 kilometres away from Shariatpur.

Nurul walks around the grave and clears the dry leaves fallen on it in the light of a kerosene lamp placed on a plastic tool nearby. Along with Nurul, who is standing by the grave, wait top officials from the district administration and armed policemen.

The unusual gathering of officials at this time of the day is to ensure exhuming of the body of 15-year-old Hena, who died a week earlier. The daughter of a poor peasant, Hena was the victim of a religious verdict or fatwa. Youngest of three sisters and a mentally challenged brother, Hena was raped, tortured and whipped before she succumbed to her injuries. Shortly after her death, the police inquest found no trace of injury marks on her body and the civil surgeon's office in Shariatpur stupefied the entire community with a post-mortem report that exactly corroborated with the police inquest. Following a report published in The Daily Star raising serious doubts about the reports, a High Court bench in Dhaka stepped in to ensure justice. “Exhume the body and let it be examined by three experts in Dhaka without the slightest delay…” was the order given earlier on that day of February 7.

For Nurul, the dome, the very thought of disturbing the dead at night gives him the jitters. There isn't even enough kerosene to neutralise the stench of the body buried a week back. He can't wait longer. “Sir, should I start digging?” Nurul asks impatiently. The crowd of about hundred villagers look on.

Nurul's 'sir', the executive magistrate (administration) Habibullah, however, is in no position to give the order as he is swarmed with journalists wanting to know why the body of Hena is being exhumed.

“We have an order from the authority to disinter (dig up) the body tonight,” Habibullah tells journalists and asks Nurul to begin his work as the clock clicks 9:00 pm.

The courtyard outside Mahbub's house where the arbitrators gathered to declare an illegal edict.

With his young assistant, Nurul takes only 15 minutes to unearth Hena, wrapped in a white loin cloth. Hena's father Darbesh Kha leans over to formally identify his daughter, still in her grave. Darbesh reacts with a sharp jerk and immediately leaves the place.

Soon it becomes clear that the executive magistrate is disinterring a body for the first time in his life. His lack of experience prompts him to call his superior every time he faces a situation. Now he wants to know whether a re-inquest is necessary before re-post-mortem.

The head of the first post-mortem team, Residential Medical Officer of Shariatpur Sadar Hospital Dr Nirmal Chandra Das, is also present. He looks tense and nervous.

At exactly 9:20 pm Nurul brings out Hena's body. A heavy stench of decomposed human flesh fills the air, forcing the waiting crowd to retreat.

Civil surgeon Golam Sarwar orders his deputy Nirmal over phone to send the body directly to Dhaka without having any re-inquest.

“We are doing this at the order of the High Court. I don't know why the order has come,” a visibly shaken Nirmal tells journalists.

Soon the coffin is taken onto a rickshaw van. As the van waits on the home yard, where Hena might have walked everyday several times, none of her family members can come out. The van, meanwhile, waits. For the first time on the home yard Hena needs one more witness from the neighbourhood to be identified. For Hena's father, mother, sisters and brother it must be unbearable, to go through such an ordeal. Even the other day Darbesh Kha had dinner with his daughter, just before Hena was abducted, gagged and raped by her cousin Mahbub.

The house where Hena was sentenced to 101 lashes.

Darbesh lives in a small hut in a cluster of homes owned by relatives. Darbesh will never forget the evening of January 23, when Hena's cries for help woke him up. He rushed out to find Hena in Mahbub's house where Mahbub's wife Shilpi teamed up with three others to unleash their rage on his little girl. Shilpi had discovered Mahbub and Hena just outside the house after he had raped the child. Incensed, Shilpi charged at Hena. Two of Shilpi's relatives, Morsheda and Jahanara also joined in for the onslaught. They dragged Hena into the house and beat her mercilessly. When Darbesh reached the place, Hena was severely wounded, sustaining a serious injury just below her left eye from beating.

With serious internal haemorrhage, Hena was still alive when she was brought back home that night. “Unable to move, my little child moaned in extreme pain with tears rolling down her face all the time,” Aklima Begum, Hena’s mother says, as she wipes tears from her eyes, “In the morning I could feel my little child needed treatment but we could not send her anywhere.”

Throughout the entire day Hena remained silent, almost unconscious. “The injury under her eye was so severe that it made her eyes look red but we could not take her to hospital.” Aklima adds, “We had a saving of only Tk 500 in cash while the arbitrators were intimidating us so that we would not admit her at the hospital. Did I act like a good mother?”

Little did poor Darbesh and Aklima know on that day that worse was yet to descend on them on the night of January 24. A vengeful Shilpi organised a team of arbitrators-- all of whom were her family members or in-laws except for the local madrasa teacher moulana Saiful and local mosque Imam Hafez Mafiz-- to come to her house at around midnight. Once the arbitrators arrived, her unfaithful husband and rapist Mahbub was summoned before them. They then asked Darbesh and Aklima to bring Hena before the "court", in the verandah of her house where the "court" headed by Moulana Saiful was waiting.

|

Nurul Islam (left) and his assistant dig up Hena's body

from the grave.

|

Darbesh Kha identifies Hena's body.

|

In the whole process Shilpi was aided by her sister Jahanara Begum, brother Akkas Meermalot and in-laws--Morsheda Begum, Idris Sheikh, member of Chamta union parishad, Yeasin Meermalot, Dil Mohmmad Meermalot, Ala Box Karati, Joynal Meermalot, Latif Meermalot, Abdul Hai Meermalot, Hafez Md Mofiz Talukder, Saiful, Monimala, Robiul Khan, Hasan Meermalot and Jamal Shikder.

“As our child was unable to walk, we had to carry her to Shilpi's house,” Aklima says. Hena had to stand there before the Moulana, who first forced Mahbub to sign on a land deed to hand over 18 decimals of land and a small abode to Shilpi, his 'helpless' wife. Shilpi had asked for the land and the home to ensure her own future as Mahbub, as Shilpi said, was unfaithful to her.

When the arbitrators were about to call off the arbitration without mentioning anything about Hena, Darbesh Kha demanded justice saying, “What kind of arbitration you are holding. What about the justice against the dishonour to my daughter?”

Shilpi's brother Akkas Meermalot wasted no time to mention that it should be done in accordance with Islami law. Shilpi's family, insisted that the incident be treated very seriously and severe punishment be meted out to the offenders. Mahbub had a history of lecherous behaviour; he had in fact forced the family to marry Shilpi off to him about 20 years back. Shilpi insisted that it was Hena, who had provoked Mahbub's adultery. About six months ago, Mahbub had been fined Tk 75,000 in a local arbitration for harassing Hena. Before that, Mahbub was slapped in another arbitration held for the same reason but he never stopped harassing the child.

|

Inspector Mirza A K Azad of Naria police station. The High Court has ordered departmental action for not filing the initial case properly. |

Now, it was Hena's turn to face the arbitrators, her parents were only allowed to sit in and listen. The arbitrators sentenced Hena to 101 lashes and Mahbub to 200 lashes. A wet gamcha was spun and knotted at one end to execute the order.

Interestingly it was Shilpi's sister-in-law Monimala who was selected for lashing Hena while Mahbub's father Robiul Kha was selected to execute the order on his son.

Halfway through the lashes, Hena collapsed. Her helpless parents carried her back home.

Darbesh Kha was so terrified by the events that he did not even dare approach the local union parishad chairman, a local headman traditionally heading the village courts. Shilpi bypassed the official members of the shalish and resorted to fatwa.

Hena was admitted to Shariatput Sadar Hospital on January 25 as her condition worsened.

Yet, Darbesh Kha's 15-year-old daughter was alive and trying to recover. But Darbesh's social status in the state structure of power is so insignificant that the perpetrators started spreading the rumour that Hena was being kept at the hospital unnecessarily for a long time to realise money from them.The perpetrators branded Darbesh “a liar” and threatened to file a case against him on charge of cheating if he did not bring Hena back home from the hospital.

Darbesh Kha and Aklima Begum, Hena's parents who could not save their child from the wrath of the influential and corrupt.

Idris Member, an architect of the fatwa, prevented Darbesh from going to the police station. Finally the family brought their dying daughter back home from hospital on January 30.

The following day, at home, on January 31, Hena's condition deteriorated fast. At around 8 pm the family took Hena to the Mulfatganj Upazila Health complex where a doctor declared her dead.

Having completed a series of formalities at the health complex, Darbesh Kha returned home with his dead daughter. A cunning Idris, present there, now sensed that things were going out of hand and advised Darbesh to put the dead body in the house of Mahbub, where Hena had sustained the fatal injuries.

The following day at around noon, Sub-inspector Aslam Uddin having been informed by the health complex of an unnatural death, arrived at Mahbub's house for the inquest. Hena's body was then transferred to Shariatpur Hospital for autopsy before it was buried on February 1.

Having exhumed the body police now wait on the yard of Hena's house for one more last witness from the neighbourhood before the body leaves for Dhaka. Noone comes forward.

“My daughter left me behind to see this scene. Put me in the grave with her,” cries Darbesh Kha from inside the house as police wait outside in silence under a dark sky.

“Allah, why have you kept me alive for watching this face?” Darbesh goes on repeating the same line incessantly while his wife only cries out: “Allah, Allah.”

The latest autopsy of Hena, which was held on February 8 at the Dhaka Medical College and Hospital, found eight external and seven internal wounds on Hena's body. The DMCH autopsy also found four bruises on the chest, three on the back of the abdomen and one in the left thigh. The external bruises were on average four inches long and two inches wide.

The internal ones, the report said, were mostly four and a half inches long and three inches wide. The wounds included three in the chest, three on the back of abdomen and one in the left thigh.

The High Court bench on February 10 comprising Justice Justice AHM Shamsuddin Chowdhury Manik and Justice Sheikh Md Zakir Hossain termed the first autopsy report a blatant lie and rebuked the civil surgeon and the doctors involved in the autopsy.

Following the fresh post-mortem report, the court passed eight directives, including filing of a fresh case and action against investigation officer of the case and the police inspector who wrongly filed the case in fifteen days.

A fresh case has already been filed with Naria police station on five charges while the earlier case filed on murder charge has been transferred to the Criminal Investigation Department for investigation.

Other directives include probing the conflicting post-mortem reports to find out if the responsible doctors were negligent in carrying out their duties in a month, a countrywide campaign against fatwa as a criminal offence, and providing security to Hena's family.

As the team of government official and police waited for the last witness to come the entire village looked like a desert sleeping in silence.

“Sir, where is my fee?” asks Nurul breaking the silence at one stage.

“Don't you see the condition and status of the family? How do you expect money?” argues the Naria police station officer-in-charge Abul Khair giving a Tk 500 note to the man from his own pocket.

“Sir, five hundred is too little money for so big a job,” replied Nurul. The puzzled police officer delves into his pocket again and hands over another Tk 300.

At this stage, Hena's younger brother Iqbal, a mentally challenged boy, comes out to sign as the witness for her sister's dead body.

“We don't consider disabled persons as witnesses,” says someone from the board of officers, “We don't need a witness in that case.”

Escorted by police the van leaves for Dhaka, Hena's body makes the lonely trip to court for justice.

Cruel and Unusual Punishment

Religious courts where fatwa or religious edicts are pronounced informally exist in almost every village across the country. When an imam of a mosque or a so called religious leader in a village gives an edict, simple God- fearing people, as most villagers are, are forced to accept it. But the basis on which the punishment is given almost always remains totally in the dark, unknown not only to the victims but also to the religious book that is supposed to prescribe it.

For years, village arbitrators, especially these religious courts have enjoyed immunity despite horrendous incidents related to pronouncement of fatwa. According to NGO workers, it is only when deaths occur due to pronouncement of fatwa, that the perpetrators may get punished.

Throughout the country fatwa is given in many ways: calling for a total ostracism of the offending person or a family from the community, forcing a separation after an angry husband verbally divorces his wife, or forcing a temporary marriage of the wife willing to live with her husband after the verbal divorce and lashing someone for alleged adultery. This is not where it stops. These religious arbitrators have pronounced fatwa against Non Government Organisations fighting for the rights of women and other social injustices too. They have, in the past pronounced fatwa against the moon sighting committee which decides the day of Eid, the religious festival. In 1994 they passed an edict forbidding the observing of the International Women's Day. The same year , in a publicised fatwa, religious arbitrators forbade singing of the national anthem and hoisting the national flag in Rangamati.

However, there are instances when fatwa for even conscious people become inevitable. For instance, recently in a remote village of Barisal a religious leader had a dispute with the imam of the mosque. The angry man boycotted the mosque where he had a dispute with the Imam over a trivial religious matter. The man went on to select a piece of land belonging to him and built a mosque, not very far from the first one. The matter put two groups of villagers confronting each other. It rolled on to the local administration. The local administration, in turn, asked a fatwa board to decide whether or not two mosques within such a small distance could operate. The fatwa board decided in favour of both mosques operating. The story ended happily.

According to newspaper reports between 1995 and 2010 there were 503 incidents of fatwa in the country.

Surprisingly, the law of the land does not prohibit fatwa. In 2001 a High Court bench, comprising Justice Md Golam Rabbani and Nazmun ara Sultana, stepped in to declare fatwa illegal. But two religious leaders challenged the verdict and put its implementation procedures on a halt. Curiously, the hearing of the case has never taken place for the last ten years.

However, a three-member bench of the Appellate Division headed by Chief Justice ABM Khairul Haque on February 14, appointed 10 senior lawyers as amici curiae (friends of court) for their expert opinion on the long pending appeal against the High Court verdict that declared fatwa (religious edict) illegal.

The amici curiae are TH Khan, Rafique-ul Huq, Mahmudul Islam, M Zahir, Rokanuddin Mahmud, AF Hasan Ariff, MI Farooqui, ABM Nurul Islam, Rabia Bhuiyan and Tania Amir.

One of the cases of fatwa that stunned the nation dates back to 1993 in Chatakchhara village under the Kamalganj upazila in Maulavibazar. A group of nine arbitrators led by Maulana Mannan sentenced Noorjahan, a housewife, to be stoned 101 after she would be buried waist-deep. Humiliated and disgraced, Noorjahan took her own life immediately after the execution of the verdict. Her tragic death instantly created such an outcry throughout the country that the police were forced to take action and arrest the nine criminals. Each of the nine criminals was sentenced to seven years of imprisonment by a court of justice of the land.

The most recent case of Hena of a remote village 30 kilometres from Shariatpur would have been suppressed and forgotten by now had the press been non-vigilant and High Court non-reactive. With Hena's murder, rape and assault cases being subjudice, we as a society must unite against this social evil called fatwa.

– MORSHED ALI KHAN

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |