|

Special Feature

Forced to Sell their Land

On October 23, 2010, several thousand people took to the streets in Rupganj, demanding withdrawal of the army that allegedly forced villagers to sell land for developing the Army Housing Scheme. The skirmishes that followed left one killed, three missing and nearly fifty people bullet-hit. Although nothing has been revealed yet about the missing youths, villagers at large want peace restored.

Rifat Munim

Moniruddin (not his real name), a 60-year-old farmer residing in the Bariasoni village under Rupganj union, had decided to get his daughter married before he died. He also had plans to provide his youngest son with some cash so that he could start a business. So he had wanted to sell some five kathas (720 sq ft equals one katha) of his land.

Finding a good bidder who was offering no less than two lakh for each katha, he hastily went to the office of land registry adjacent to Rupganj thana. But much to his disappointment, he relates, he found there two army officials telling him that he could not sell his land to anyone else other than the army. However, the need for some hard cash outweighed his hope of a fair bid, so he gave in and resorted to the army for selling his land. But when he was offered less than half of the current price, he was shattered.

|

Villagers of Tanmushuri mouja torch an army camp after the troops were airlifted. |

“It was my land, so I should be the one having the exclusive right to decide on when to sell and to whom. But they made it crystal clear to me that I can sell my land only to them, and that too, at the cheapest price,” says a distraught Moniruddin.

The worse had happened to many of the 24 moujas (a cluster of villages) of Rupganj and Kayetpara unions. Some had wanted to pass down a portion of their real property to the next generation while some had wanted to sell so that they could perform hajj, the ultimate spiritual pilgrimage for Muslims. But whatever the case, the villagers were left with only one option, that is, either sell it to the armed forces at the cheapest price or refrain from selling.

It should be mentioned here that the army personnel set up camps in several parts of Rupganj and Kayetpara unions, and had been trying to purchase land for months from villagers to develop the Army Housing Scheme (AHS). They were allegedly obstructing villagers to sell their land or hand it down to the next generation according to the inheritance law.

Eventually the pent-up frustration and despair led to a mass outburst. Several thousand people irrespective of their age and gender gathered round the army camps especially near the Tanmushuri and Ichhapura camps demanding immediate withdrawal of the army from the villages. A pitched battle ensued as the army allegedly opened fire first leaving more than fifty persons bullet-hit, one killed, and three youths missing.

Following the clash, as the so-called AHS in Rupganj came in the spotlight, the army spokespersons defended themselves by saying that the housing project was approved by the government. However, State Minister for Housing and Public Works Abdul Mannan Khan denies his knowledge of any such approval.

“I have not heard of any such project. If there was any, then I would know it,” says Khan in a telephone interview. Rajuk Chairman Nurul Huda, despite several attempts, could not be reached.

Nearly four months have passed since then. The green landscape dotted with paddy fields along with the quiet life of the villagers will give an impression of restored peace in Rupganj which means 'beautiful village'. But as you stop by a gathering in a nearby bazaar and start talking about their furious protest against the army, the uneasy looks on their faces give away the scars that remain. The atmosphere is grim with the weight of the disappearance of three young men who had been part of the protests. With no news of whether they are dead or alive, the distrust of the villagers towards army personnel and law enforcing agents has further deepened.

|

| A policeman tries to pacify a villager during the clash between villagers and the army. |

As many of the villagers refuse to talk or comment on that day's events, you realise that they are very much aware of the three cases filed against them by police, Rab and army respectively, investigation of which are underway. Each of the first two cases has accused 3000 to 4000 unidentified persons whereas the third one filed by the army has accused about 50 persons. Although the army has withdrawn its camps and stopped its activities related to the AHS, a fear that they will be arrested still exists among villagers, barring many of them from commenting on that day.

However, Sahar Ali of Baniasori, who lost his son to that day's battle, has no fear whatsoever. His son Abdus Salam Masud, the breadwinner of the family, is one of the three missing youths.

“I clearly saw the Rab men shoot him first and then lift his body into their vehicle. Since then we have searched for his body in several hospitals, but to no avail. I have also filed a GD with the Rupganj police station, but they are also in the dark about the whole thing,” says Sahar Ali.

Family members of Masud, his parents and sisters, and his widowed wife, all have by now accepted that Masud died on the spot that day. “But why didn't they return the corpse of our son? Why isn't he declared dead?” agonises Ali.

However, Commander Mohammad Sohail, director of Rab's legal and media wing, refuses to make any comment about the missing youths since all the events and the violence that followed are now under investigation.

|

| (From left to right) Masud, Saidul and Shamsher-the three missing young men. |

“What actually happened that day is now under investigation. So no comment should be made before the verdict is delivered by the court,” he says. Asked if the Rab men shot at the people to disband them, he says, “The people grew so violent that we had to interfere since we are responsible to bring any chaotic situation under control. If we were not there, then villagers would have seen much more bloodshed than what has actually happened.”

Such explanations are not convincing. Although villagers fear arrest for they are accused in three cases, they have not yet seen any investigation officer. They also doubt the accountability of the investigation and believe that any further development of the cases will just serve the army's purpose, mystifying the incidents of killing and shooting. Secondly, the people were violent only after the news spread that the army had shot villagers at the Tanmushuri camp.

“We had not thought of such a huge crowd. But when the news of villagers having been shot spread, thousands of people from all the villages started to flood the area. Even in this second phase, the army and Rab men opened fire first,” says a middle-aged man on condition of anonymity.

Villagers of Tanmushuri mouja also allege that the army personnel shot at the protesters first. But the irony lies elsewhere. Even though the army and law enforcing agencies opened fire in defense, none of them were even seriously injured. About the army's role in the incident, Md Shaheenul Islam, director of ISPR (Inter Services Public Relations), says that he will let the concerned authority know about this. But at the time of writing this report, no reply from the ISPR or the concerned authority had arrived.

|

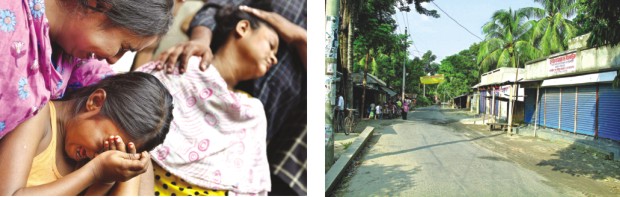

| Masud's grieving family breaks into tears. |

An empty road at Rupganj as males were on the run immediately after the event. |

Sultana Kamal, the executive director of Aine O Salish Kendra, firmly opposes the idea of acquiring people's land in such a way and asks for revealing the whereabouts of the missing youths.

“The AHS project, as it was dealt with in an equivocal manner, should be withdrawn from Rupganj. People who were forced to sell land should get back their land immediately,” she says.

About the missing youths, she says, “It is a very sensitive issue. Yet, if we are provided with legal documents, then we can file a writ petition asking for a probe into the matter.”

|

A map showing the AHS in Rupganj. |

Saidul, another missing youth of the same village, was also the breadwinner of his family. His family consisting of old parents and a school-going brother now lives from hand to mouth. Stricken by grief, Rahazuddin, his father, can barely speak and does not seem to be capable of earning his livelihood, let alone procure all those legal documents necessary to challenge law enforcing agencies.

“They killed my son for nothing. Now I have nothing left except for two cows. How can you run a family of four with this?” he cries.

Rahazuddin believes that his son is dead. All he now cares about is how to run the family. “Why should so many journalists and lawyers come to me? I'll not get my son back anyway. Now I need something to get by,” he asserts.

At this point, one cannot but wonder why so many people who literally have no land property spontaneously took part in the protest. Since the army set up camps near Ichhapura bazaar, villagers allege, they tried to interfere with their social as well as private affairs.

Representatives of various human rights organisations in a roundtable demand immediate closure of the AHS in Rupganj.

“There are specific laws about offences, be it capital or small. If there is something wrong in the village, there are law enforcing agencies who should then take things into their hands. But why should the army poke their nose into our private affairs even though we didn't ask for their help,” says a villager requesting anonymity.

People like Sahar Ali and Rahazuddin have sustained the double blow of poverty and a fatal loss. While their cries for justice and material help should be addressed in no time, farmers like Moniruddin should be given back their right to their land, so that they can make use of it in whichever way they feel like. Finally, calm should be restored so that villagers can move freely and live peacefully without ever having to witness protectors turn into intimidating land-grabbers.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010

|