| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 17 | May 06, 2011 | |

|

|

Cover Story

A Film, a War and so Many Questions "Guerrilla” is Nasiruddin Yousuff's latest, most ambitious, and extremely bold, and which, I hope will become, his most successful cinematic venture. The film is based on the events of the initial days of our Liberation War, just when war was beginning to acquire its momentum and people, mostly youth, were getting organised to make some dent on the monstrous Pak Army. For those who will see this film I have only one suggestion to make. At the end of it just ask the question: “What would have happened to us -- as a people, as a culture, as a society, as a historic entity--if we had lost the war?” Please do not answer the question in a hurry. Let the scenes you saw churn in your mind. Let the facts depicted in it sink in your consciousness. Allow them to trigger introspection and try to understand what the Liberation War really stood for. Would you ever have been able to raise your head in pride if we had lost that war? This write up is not about the film but the events that the film depicts. It is not about how authentic each of the scenes is but about the authenticity of the bigger narrative, about the brutality that our people had to suffer. I am not a film critic and this piece is not to tell you how brilliant the film is (which it is) but how important the film is. The film is not simply about the brutality that our people were subjected to but about reminding us all how our very existence as a people, as a culture and as a historic entity were at stake, and what unimaginable consequences we would have to suffer from if we did not win in that mortal combat. I write today because I am a proud freedom fighter who is a personal witness to those glorious days and to some of the events depicted in the film. I personally knew many of the characters that the film depicts and hence there is a lot of emotion in every word that I am writing today.

The film is an important testimony to our independence struggle and must be seen by all, not only to remind us of those glorious days but also to show respect to all those who laid down their lives so that we can live free. Two fundamental features of the film deserve to be noted. The director chose a woman to be the film's main protagonist and thereby brought out the contribution of our women freedom fighters. This is vital, as so far the contribution of women in our freedom struggle had not been highlighted at all. Second is that the film tells the story of those who fought the war from within the country, from behind the enemy lines, so to speak, rather than those who were in the Mukti Bahini camps in the bordering areas. Here is a “first” by Nasiruddin Yousuff as not much is known about the bravery of the people who actually crippled the Pakistan Army from within and destroyed their morale and self-confidence. The film made me sad, outraged, angry, worried and of course proud. Sadness springs from the memories of the sufferings of millions of our people for the simple crime of asking for their right to speak in their mother tongue, live in their own cultural and do so in freedom. It reminded me of the friends, relatives and co-political workers that we lost, bringing back the vivid memories of the all round fear in which we lived and cruelty suffered by our people at the hands of Pakistani armed forces, which was till then supposedly “our own” army. As I recall those barbaric days, my heart is filled with the sorrow of the senseless killing that was perpetrated on us. I am sad because, in my mind's eye, faces of so many of my friends and acquaintances resurface who died during the first 24 hours of assault on the Dhaka University campus, where I was a BA Honours student. Two Halls (student dormitories) were the primary targets; one because it housed Hindu students and the other because it was the command centre of the students who led the movement at that time. The machine gun sound still rings in my ears, as everybody who was in Dhaka on the night of March 25 will have heard. It was relentless and non-stop with occasional flares of fire rising to the horizon especially from University area, Pilkhana and Rajarbagh, the two latter locations were headquarters of EPR (East Pakistan Rifles and police). All these memories evoked by the film filled my heart with a deep sorrow that I am finding so very difficult to bear even after nearly 40 years of the events depicted in the film. I am outraged by the memories of how racial, dehumanising and fundamentally insulting the views of our oppressors were about us. Over the years in united Pakistan racial undertone marked us a cowardly people who did not understand the meanings of freedom and could only be controlled by the “danda”(stick) meaning military rule. The “Bloody civilian” was the usual refrain that seemed to be reserved for us.

Our religious feelings were seen mostly as superficial since we came from the Hindus who were converted. So in everything we demanded and fought for “could not” have emanated from our own mind but were dictated by the Hindus from India. So our demand for Bangla as a national language was instigated by India, our demand for regional autonomy was to “weaken” Pakistan, again an Indian agenda and our “desire” to read Tagore was nothing more than a perpetuation of Hindus' hold on our thought process. My anger is upon ourselves when I think how we squandered the opportunities opened by our independence and frittered away a magnificent opportunity to show the world what we are capable of. We brought ourselves to such a pass that the very coterie that the film depicts of having collaborated with the Pakistan army could not only get rehabilitated but even come to power in independent Bangladesh. My worry comes from my thoughts as to whether or not we have learnt enough from our past mistakes so that now we can truly build our Sonar Bangla. I would like to conclude with a deep sense of pride that the film evoked within me. Pride because we fought and won a war with one of the fiercest army in the world and we did so literally with bare hands, so to speak. I am proud that in spite of all the atrocities and oppression we did not bow our heads and saved our culture, language and our way of life from the hands of a most well equipped army backed by a people who did not think us as their equal in any way, but in fact thought us to be inferior in most ways. I am proud that we not only became independent but have been able to build a country which is democratic and open, and which in spite of tremendous challenges and occasional pitfalls, has moved forward, if slowly, but definitely steadily. I want to thank Nasiruddin Yousuff and his whole team for bringing back some very vital parts of history back for contemporary Bangladesh that, I hope, will help us to revive the spirit that united us 40 years ago and made the world notice us. I am not asking for some breast beating bravado but for some mature introspection and deep questioning of what we have fought for and where we have come, and inexorably going towards. ..............................................................................................................................................................

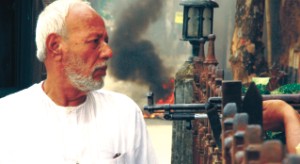

Mutilated body parts and distorted human faces juxtaposed with an agonising horse muzzle- all stacked up in a pile may remind one of Picasso's unparalleled work 'Guernica' painted in the context of a war. But an identical image complemented with rotten blood spilling all over the heap is precisely what reminds Nasiruddin Yousuff of our liberation war. And it is with a cluster of such horrendous images that the film 'Guerrilla' begins. Although similar images return every now and then to imply the indiscriminate killings inflicted throughout those horrific nine months, acts of guerrilla resistance soon take over with grenades exploding like a fiery flame symbolising the strangled revolt of an indomitable people that has never bowed down to an oppressive military regime. Thus Yousuff, one of the pre-eminent theatre personalities, with a flair for directing brilliant stage-plays, has put into this enormous work all his artistic craftsmanship culled from theatre, literature, music and painting to make a film which can be evaluated only on an epical scale. Rifat Munim From the very beginning of the film, instead of relying on the freedom fighters as any traditional narrative would do, the film brings out the lives of those who have not joined the war directly, but stayed behind and contributed enormously in the war in so many ways, and more often than not gave their lives to win it. That is not to say, the matchless sacrifice of the fighters has been left out of focus. Quite the opposite, the fighters have been portrayed even more graphically both in organised and guerrilla fighting. Their portrayal, however, is as much a part of the film as other characters, whether major or minor, who stayed behind. The only fully developed character is the protagonist Bilkis who, through her activities in Dhaka and her journey to her village connects all the separate parts to form the whole of the film and capture the totality of the war. “I did not try to rewrite history. That is the task of a historian. Although I've taken the historical context of 1971 as my subject, I have tried to turn that milieu into an art work by manipulating the form of film, but also incorporating in the process the various other forms of poetry and painting. In so doing, I've been very loyal to history,” says Yousuff with the characteristic determination in his voice. “There are scenes of gruesome killings in the film because such gory deaths had really taken place. But there are also flowers, birds, dreams and above all, love.”

Beginning with a happy couple Bilkis and Hasan, played by Joya Ahsan and Ferdous respectively, the film draws on the brutal mass killings by the Pakistani army on the night of March 25, the night that had seen one of the deadliest genocides in human history. Hasan, who is a patriotic journalist by profession, disappears on that night. What follows, however, is an abrupt leap taking the tale unpredictably to the month of August. But as the audience finds Bilkis again, albeit a completely different Bilkis publishing and circulating an underground magazine called Guerrilla, and working as the nucleus of a flurry of guerrilla attacks on the occupation army; it does not take them long to keep pace with the narrative. “It is not possible to deal with every single month of the war in an artistic work. I have to carve a story through which to give an artistic presentation of the war that would cut out some parts yet would retain its gravity and vastness,” says Yousuff explaining why that sudden leap had to be made. He tries to make his point clearer. “You can at best try to incorporate as many different lives as possible. There'll still be a huge gap which I have tried to bridge with a number of symbols and allegories. That's why my film need not be extended to December and ends in August.”

Bilkis is also a working woman and a responsible daughter-in-law. But she is not the exalted, glorified stereotypical housewife who does all the household chores and serves as a perennial source of inspiration for her husband or beloved who, in his turn, joins the freedom fighters and promises to come back when the country is free. Far from that, Bilkis is a selfless, committed freedom fighter who, disguising herself provides grenades and explosives to co-fighters. Risking her life, she deceives the high-ups of the occupation army at a party in Dhanmondi with the collaborators and the local elites, and sets a bomb there that explodes minutes after her departure. This is the first part of the film that deals with Bilkis' stints and exploits in Dhaka with her co-fighters such as Alam and Shahadat.

“In all the eleven sectors throughout the war, countless women actively took part in the war and sacrificed their lives as fearlessly as their male counterparts. But when it comes to documentation, whether historical or artistic, all we find is an incomplete list of rape victims who, too, were badly treated after the war. Well, then what about the real female fighters? Have we ever paid a tribute to their immense contribution? That's why I've cast a strong female fighter as my protagonist,” reveals Yousuff. The first part has many other ramifications entangled in a number of major and minor characters. The two major characters in this part are Altaf Mahmud, the gifted composer of all times who also helps the freedom fighters in any situation, and Taslim Sardar, a progressive elderly man in old Dhaka where Bilkis lives. Mahmud and Sardar have been played by Ahmed Rubel and ATM Shamsuddin respectively. Among the minor characters are Taiyeb, Binni, Professor Anwar Pasha, Naren and Jahanara. None of these minor roles are fully developed. Their stories are rather fragmented, yet eventually turn out to be an integral part of the film.

As the film approaches the second part, one cannot but notice the overshadowing of a gloomy atmosphere, marked by a dearth of sunlight. In fact, throughout the film, the sky overhead is overcast, an effect which is perfectly consistent with the sheer uncertainty of a nation reeling under the ominous dark clouds.

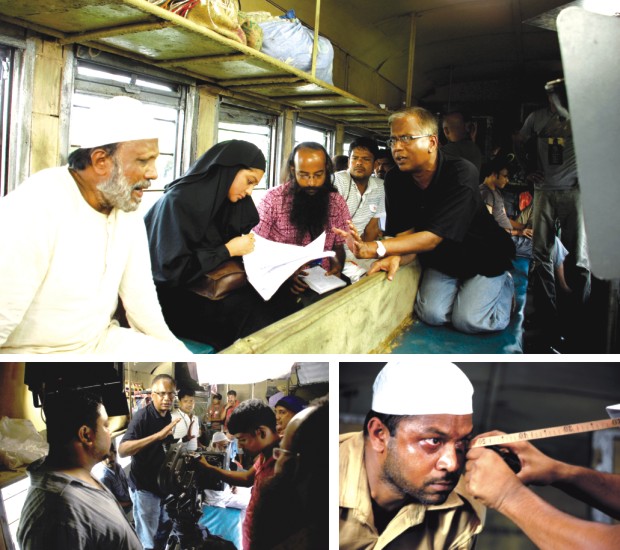

“It has been done deliberately. All the scenes of the film have been shot in cloudy weather. When there was no cloud, we had to wait, sometimes even for two days. The overcast sky is intended to correspond to the context. The original bright colours of daylight have also been blurred in the film for the same reason,” informs Yousuff. In this part, Bilkis is seen fleeing by a train to her ancestral home in a village where her brother Khokon, a commander of freedom fighters, lives. This journey becomes the most sustaining allegory of the film, representing the uncertainty hanging over the nation and the victimisation of its people. Along with Khokon, Siraj is another major character who is a Hindu by religion and who unexpectedly appears to accompany her when the train stops halfway. Both of them face a similar fate as that of Taslim Sardar's. Compounded with allegory is Yousuff's manipulation of excellent poetic images in the shape of flashbacks of childhood, the bright colours of which instantly form a contrast with the present where there is no bright colour. His use of myth, especially the one about a sibling's transformation into a bird after death, lends insight into the culture of the country. But what adds quite a different dimension to the tale is the songs and background music. “Think of the song when Naren is caught and slaughtered because he is a Hindu. There are other striking examples as well. I think Shimul Yousuff along with her team has demonstrated extra-ordinary powers in blending the songs with the appropriate scenes,” the director says. The ending, however, constitutes the most artistically successful moment of the film. Having been caught by the army, when she is sexually assaulted by Captain Shamsad, she does not give in and resists with all her powers. “With such a revolting act of self-sacrifice, her uncertain, allegorical journey comes full circle and the flame emanating from the explosion in the last scene symbolises the outburst of a nationwide revolt that cannot be subdued any more,” says Yousuff.

The train journey, however, is apt to remind one of Syed Shamsul Haque's novel Nishiddho Loban, one of the most acclaimed literary works on the liberation war. Most of the second part is based on the novel. “I'm too grateful to Haque Bhai for his excellent, allegorical story. Even this tale is based on a true story. He heard this tale in 1972 from Khaled Mosharraf, the commander of sector 2. While this is a highly commendable approach to our war, I still found it inadequate to capture all the facets of the war,” he says. So in the construction of the plot as well as of the characters, he has coalesced his own experience with the tale of Haque's. Nasiruddin Yousuff, known to the cultural scene as a frontiersman both in theatre as well as in the streets, was a freedom fighter. As a young man of 20, he, along with his friends Rumi (son of Jahanara Imam), Raisul Islam Asad (actor), Azam Khan (singer) and Sadeq Hossain Khoka (incumbent DCC mayor), among others, had fought pitch battles with the occupation forces mainly in Dhaka and its adjacent areas, and that too as a commander of the northern part of sector 2. Moreover, it was under his direct supervision that a group of young men and women had published a magazine named Guerrilla. “When we were fighting in different areas of Dhaka, we had, among other women, Mini Kader who had a bank job, Anjum Kusum who was involved with the magazine Guerrilla, and Zakia apa. Maybe many of these characteristics have converged in Bilkis. I have taken the liberty of fictionalising sometimes, but even the fictitious parts are predicated upon facts,” he explains.

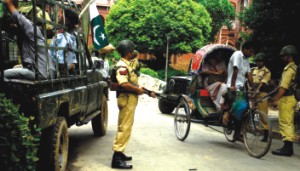

Not only Bilkis, the first part as a whole is a reflection of what he had seen through the war in Dhaka. Perhaps, such direct experience accounts for the convincing portrayal of the upheaval as well as the setting of the city whereby an authentic ambience of 1971 has been recreated in the film. In spite of a storyline with Bilkis at the centre, the story often strays into the lives of other characters. Sometimes these meanderings are done at the expense of coherence in the narrative, for example, the sudden insertion of the fairy tale episode from her childhood when she is in the train and similar flashbacks. Sometimes the characters thus touched upon have been left incomplete. Yet, it was through these ramifications that Yousuff seems to have reached the sublime. “I believe that the liberation war is the most creative and significant moment in our history. It blessed for the first time a Bengali-speaking people with an independent, democratic state; promised thereby an egalitarian society that would provide all with the basic rights. Then think of the nature of the war: it was a true people's war wherein people from all walks of life contributed and suffered to which I am an eye witness. Such stunning sacrifices that lie behind this massive war deserve an epic treatment which like the Mahabharata would incorporate a thousand tales,” says the director. But how to incorporate all these different tales and facets in a film? “Characteristically, in order to contain the whole of a culture, the epic brings out a thousand of small, apparently insignificant tales. So I had to touch upon a thousand lives to show the diverse ways of their sufferings and contributions. That's why the focus is scattered over so many characters. That's why almost all the minor characters are presented in fragments. What links them together are the symbols, images, contrasts, allegories and the myths,” he explains. The massive set also testifies to Yousuff's all-out efforts to make an epic. The scripting began in September 2009 and the shooting in May 2010 which continued till October. Then the post-production works including editing, sound mixing and special effects were completed in India in April 2011. While making the film, the first challenge was to recreate a Dhaka of 1971. The only available archaeological site was the 400-year-old Panamnagar in Sonargaon. In it he had to rebuild a city where there are no giant billboards, advertisements and high-rises of the present day. He had to put up the old-styled light posts, put new colours on the walls and buildings. Even the rickshaws and baby taxis were painted newly and the texts on them were written in Urdu. “It was really a hectic task to rebuild Panamnagar. But similarly difficult were the battle scenes which would not have been possible without the massive help of the Bangladesh Army, Bangladesh Police and Bangladesh Air Force,” remembers Yousuff.

In the first battle scene, with the permission of the IG of Police, he used the real three-not-three rifles used by the police officers of Razarbagh on the night of March 25. In other scenes, he used real ammunitions including tanks which were provided by the army. The helicopters and jets were provided by Bangladesh Air Force. A part from these, another challenging task in the making was the rebuilding of the train. “The scenes in the villages including those in the train were shot in Lalmonirhat, Parbatipur, Dinajpur and Rangpur. When I contacted the railway officers, they said they would be able to provide me carriages that need to be repaired. Then I started working on all the left-out carriages and it took me five months to get the repair completed. The train scenes were shot in 11 days but for the other scenes in the village, I had to stay in the villages for two months with my whole team. In this regard, I must admit that without the spontaneous assistance of the DCs, SPs, and officials of the local government and common people, completing the work would not have been possible,” recalls Yousuff. A total of 4,500 people have acted in the film, although more than 100 were active, and the rest were passive characters. During the shoot in those villages and districts, about 400 people stayed there on an average. Activists of Gram Theatre, Group Theatre Federation, and Sammilito Sangskritik Jote acted many of the roles spontaneously as well as voluntarily. But the most memorable part of these days is the dedication showed by the crew and cast present there. “One day suddenly the director of photography Sameeran Dutta fell so terribly ill that I decided to stop shooting. But he insisted on continuing in that condition. The same happened to Joya. Her face was infected and got swollen, but ignoring everything she continued acting. So what you now see is the result of the selfless sacrifice of thousands of people,” he remembers. In the art scene of Bangladesh Yousuff is best known for his commitment to a cause. The objective of making this film is not any different. “In the film I've clearly shown who were our enemies and who were friends. In addition, I've also shown how spontaneous, fearless sacrifice of Bengalis irrespective of their cast and creeds has made the birth of Bangladesh possible. By showing these facts I want to arouse in the present generation the same commitment that people in those days had shown. Through this film, I want to tell them that there is no scope for complacency and everyone must come forward to build the country otherwise the heinous people of Jamat-e-Islami against whom we had once fought would again rise to power,” concludes Yousuff.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |

||||||||||

Guerrilla

Guerrilla