| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 17 | May 06, 2011 | |

|

|

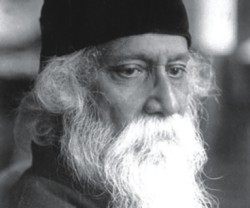

Literature On the Seashore of Endless Worlds Rabindranath Tagore towered over the landscape of the Subcontinent, and KAISER HAQ

The 150th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore, in May 2011, will mark the high point of a prolonged hoopla that has been going on for a year and will continue for another year at least. India’s cultural institutions have organised seminars, conferences and performances worldwide, including several in collaboration with Bangladesh. Within India there is no end to celebratory events, especially in West Bengal. In Bangladesh, which boasts the world’s largest Bengali-speaking population, a commemoration committee has been formed, with the prime minister in the chair. Not to be outdone, the British Council has already sent the Bangla-Brit dance maestro Akram Khan and his troupe on a Southasian tour, putting on Tagore dance dramas in collaboration with local performers. Stretching things a bit, the British Council has also brought a writer over from London to Dhaka to conduct a Tagore-inspired creative-writing workshop, and has sponsored a Tagore-related fashion workshop culminating in a catwalk parade. Publishers too have got in on the act, and numerous anthologies and individual volumes of or on Tagore, in the original or in translation, have appeared or are on their way. There was a similar flurry over the Tagore centenary back in 1961. But soon thereafter, to the wider world at least, he was once again an exotic voice in the wilderness. Will the pattern repeat itself this time around? It well might but ought not to, for there is much in Tagore’s multi-faceted talent to enrich the cultural life of our postmodern millennium. In fact, there are several Tagores: by my reckoning, three Indian ones and three international ones. In his native region of Bengal he is, in Nirad Chaudhuri’s tart phrase, ‘the holy mascot of Bengali provincial vanity’. Very different is the ‘real’ Tagore, available to the discerning reader of the original Bengali writings, placed by Chaudhuri in the universal top 20 writers of all time. There is also an ‘all India’ Tagore, available to non-Bengali Subcontinentals in translation, either into English or a regional language. Outside the region there is, first of all, the Tagore who was briefly admired by the West as a great poet and who played a catalytic role in the emergence of Anglophone modernism. The simple, cadenced prose of the Gitanjali, the collection of English poems that won him the Nobel Prize in 1913, acted as an inspiration, though not quite as a model, when the American Ezra Pound and the Irishman W B Yeats were trying to take traditional poetry and ‘make it new’. Fame then cast Tagore in the role of poet-guru, widely translated into European languages and adulated as what Americans might call an ‘inspirational speaker’. In Germany after World War I, he became a cult, followed by hysterical groupies. His outlandish appearance – ankle-length robe and a beard growing ever more resplendent with the years – was an asset in such a role. The English writer Ernest Rhys declared that Tagore reminded him of ‘the prophet Isaiah’. When Tagore went to see the traditional passion play at Oberamm-ergau, Germany, in 1931, the awestruck audience whispered that he looked like ‘Our Prophet’. The apotheosis was completed when a Buenos Aires dressmaker exclaimed that Tagore looked like ‘God the Father’. The Indian god’s twilight came in Germany with the rise of Nazism. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, branded him an agent of ‘world liberalism’, which in his perverted vision was a terribly nasty thing. Another Nazi even claimed that Tagore was actually a Bombay Jew called Rabbi Nathan, who had cunningly adopted the pseudonym Rabindranath! In the Anglophone world, Tagore’s reputation declined after the appearance of three translated volumes of poetry; his later books had a rather lukewarm reception.

Simple, clear straightforwardness Tagore’s career leaves one overwhelmed by the sheer scope of his achievement. Albert Schweitzer, the philosopher, was spot on in dubbing him ‘the Indian Goethe’. In all he published – if I have the count right – 51 volumes of poetry, 95 short stories, 40 collections of essays, 52 plays, seven travel books, 12 volumes of letters, and 14 novels and novellas, which provide the finest portrait of Bengali society from the late 19th century to the 1930s. He also wrote over 2000 songs, set them to music and sang them. He produced his own plays and acted in them. Taking to art with sudden enthusiasm in his mid-60s, he turned out over 3000 paintings and drawings, and came to be acknowledged as the greatest Indian artist of modern times. His life and art are informed by a coherent system of ideas, with ramifications into philosophy and religion, socio-political theory, education theory and aesthetics. He studied and practised homeopathic medicine, managed large ancestral estates, set up the ‘world university’ of Viswabharati at Santiniketan, experimented with rural economic reform at Sriniketan. Rabindranath Tagore was born in Calcutta on 7 May 1861 into a family that was one of British India’s most distinguished and yet socially stigmatised among the Bengalis, owing to an ancestor having compromised Brahminical purity through association with Muslims. Furthermore, his grandfather, the merchant-prince and philanthropist Dwarkanath, defied caste rules by sailing to Europe several times; he died there, as did his friend, the social reformer Raja Ram Mohan Roy. The poet’s father, Debendranath, following a spiritual experience mutated from a man-about-town into an otherworldly Maharshi, and revitalized the Brahmo Samaj founded by Raja ram Mohun. When the family business collapsed, he paid off every creditor out of income from the family estates. Rabindranath was the youngest of 14 children, several of the others of whom likewise boasted many talents. He attended a number of elite schools, though each for brief spells, and at the age of 14 he dropped out of school altogether. Over the years he would fashion an elaborate theory of education, emphasising the importance of spontaneity over mechanical discipline. At 17, already a published poet, he was sent to England, to study either for the Indian Civil Service or the Bar. He did neither, but thanks to his varied experiences he felt that East and West had blended harmoniously in his person. In an epistolary travelogue, he pioneered the literary use of the colloquial form of Bengali, and kept up a steady flow of Romantic lyrics, essays and plays. When he was just 20, Rabindranath was hailed by Bankimchandra, the leading writer of the older generation, as a new star in Bengal’s literary firmament. He had found his own distinctive voice as a poet, a wistful Romantic voice imbued with love of nature and yearning for an elusive and yet all-too-evident divinity; like his father the Maharshi, he too had a mystical experience that left an ineradicable impression on his soul. He too took the Brahmo Samaj seriously but in later years discovered greater kinship with the mendicant Bauls, about whom he enthused in the Oxford Hibbert lectures collected in The Religion of Man. But there was also a leavening of the light-hearted, playful, comic and also of the seriously satiric, as – to give an early example – in a teenage verse mocking the aristocratic Indian toadies preening themselves at Lord Lytton’s Delhi Durbar in 1877, while their poor countrymen were stricken by famine. Rabindranath became a householder at 23, marrying a 10-year-old girl chosen by his family. Within four months his sister-in-law, Kadambari Devi, to whom he had been warmly attached, committed suicide. The predicable rumours did the rounds; they are best discounted. What is certain is that their fateful friendship inspired the story ‘Nashta Nir’ (The Broken Nest), brilliantly translated onto celluloid by Satyajit Ray as Charulata. Ray also filmed three other Tagore stories, all with female protagonists, in Teen Kanya (Three Maidens), and the novel Ghare Baire (Home and the World). Tagore’s fiction continues to be a rich mine for enterprising filmmakers: witness Rituparno Ghosh’s Chokher Bali (Grit in the Eye) and Naukadubi (The Wreck), the latter currently under production. A worldly step profoundly influenced Rabindranath’s creative life when, in 1890, he was sent to Shelidah, in East Bengal, to manage the family estates. Whether in his landlord’s mansion or on the houseboat in which he toured his domain, he was steeped in a landscape and way of life far removed from what he had experienced in Calcutta. He responded warmly and intensely to the mild air, the soft alluvium, the capricious rivers, the simple lifestyle and emotionally charged predicaments of the village folk. Over the decade he spent there, he found subject matter for more than half, and most of the best, of his stories. Rabindranath had a mature grasp on the specific nature of the modern short story, as evinced in his poem ‘Passing Time in the Rain’, which William Radice appends to his excellent translations of Tagore’s Selected Short Stories: Small lives, humble distress, In 1913, the Nobel Prize for Literature made Rabindranath an international celebrity. The British government knighted him in 1915, but four years later he renounced the honour in protest against the Jallianwalla Bagh massacre in Amritsar. For a few decades thereafter he became a tireless world traveller, and his travel writing is rich in canny observations and reflections. Disciplined Chinese coolies going about their chores on the Hong Kong wharf lead him prophetically to declare that here was a nation that would overcome all obstacles to find a place in the sun. In the Soviet Union, his appreciation of the socialist experiment was buttressed by a formidable and still relevant critique of consumerist capitalism. Rabindranath’s travels were often lecture tours through which he disseminated ideas that are more relevant than ever, for beyond being ‘inspirational’ he could also be a formidable polemicist. As World War I raged in Europe, he realised that the cataclysm was the logical outcome of rising ‘Nationalism’, the title under which he collected a series of lectures delivered in Japan and America. He put many hackles up by condemning the modern nation state as ‘the political and economic union of a people … in that aspect which a whole population assumes when organised for a mechanical purpose.’ Such a mechanical organisation can only throttle the human spirit. Southasia imbibed the European concept of nationalism with alacrity, and perversely subjected itself to vivisection. As Europe has evolved into an admirable transnational union, Southasians would do well to ponder Rabindranath’s views afresh. Darkening vision

Rabindranath and Mohandas K Gandhi enjoyed a warm friendship based on mutual respect, admiration and even reverence. But the most interesting aspect of their relationship might well be the debates they carried on in public and in print in the pages of the Calcutta journal, the Modern Review. Rabindranath upbraided Gandhi for interpreting an earthquake in Bihar as god’s punishment for the perpetuation of the caste system. On a more general note, he also took issue with Gandhi for having played on the atavistic sentiments of the masses. Though staunchly anti-imperialist, he firmly refused to go along with Gandhi’s Swaraj movement when it erupted into violence. The very title of one of Rabindranath’s essays, ‘The Cult of the Charka’, referring to the spinning wheel, speaks volumes on this topic. With the founding of Viswabharati University in 1924, Rabindranath set his heart on producing new generations of young people on the basis of his own liberal education theory. Viswabharati is now one more public university supported by the state, but in its heyday its unconventional approach to learning drew adventurous intellects from the world over. The triumph of literary modernism, which reached its apogee during the 1920s, impacted on Bengal as well. A new crop of Bengali writers, while admiring Rabindranath’s magnificent achievement, might well have begun to look upon him as something of a beached whale. But this would not be entirely fair; his art did evolve with the times. A number of his later poetry collections use free verse, and one out-of-the-way novel, Shay (“S/he”) is based on exuberant wordplay. More conspicuously, his drawings and paintings, which were exhibited to acclaim in Russia, Germany and Britain, revel in dark hues and grotesque shapes in a decidedly expressionist manner. One might well describe their emergence as the return of the repressed. Rabindranath’s creative and critical faculties remained unimpaired till his last moments. His address to his beloved Viswabharati on the occasion of his 80th birthday in 1941 – his last – had to be read out on his behalf as he was then bedridden. Subsequently published as ‘Crisis in Civilisation’, it is a cri de coeur desperately trying to balance hope against despair. Those were days of ‘graceless disillusionment’; he was sure the British would be compelled to give up India, but feared they would leave behind ‘a waste of mud and filth’. Despite the troubled times, he did not want to ‘commit the grievous sin of losing faith in Man. I would rather look forward to the opening of a new chapter in his history after the cataclysm’. From his deathbed he dictated terse, enigmatic poems of great power: When existence first became manifest The apocalyptic worldview of the Western modernists that had crystallised around World War I seems to have caught up with Tagore as World War II raged. If fate had granted him another couple of decades, I fancy he might have discovered a kinship with some of the modernists. I can certainly see him reading T S Eliot’s quasi-mystical Four Quartets with relish. Be that as it may, I hope his 150th birth anniversary will provoke a re-evaluation of his achievement, and accord him a place in the global arena of contemporary discourse. A fair index of the canonisation of writers and thinkers is inclusion as a subject in a popular series of monographs – for instance, the Fontana Modern Masters or, more recently, the Oxford Very Short Introductions. Both have included Gandhi, and rightly; but neither has included Rabindra-nath Tagore. It is an oversight that ought to be remedied. This article originally appeared in the May 2011 issue of Himal Southasian. Reprinted with permission.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |