| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 31 | August 12, 2011 | |

|

|

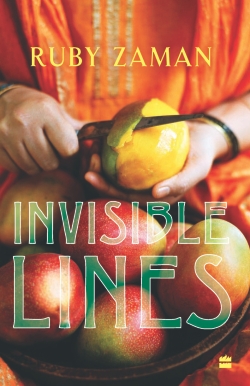

Book Review The Closure AHMEDE HUSSAIN

Bangladesh's Liberation War was a momentous affair in the history of the world. It divided the world into two bitter halves--on one side was Pakistan, actively supported diplomatically and militarily by the US and China, and on the other were the people of Bangladesh, and its allies India and the USSR. Most important in the paradigm, however, is the role of ordinary Bengalis, who took up arms to change the course of history. Some of them were peasants; some were students, day labourers and women who otherwise would have remained content in the footnote of history. In the wars of freedom across the world, be it in Algeria, Vietnam or Iraq, individuals' class characters take a back seat, and the people's urge to free themselves from the shackles of occupying forces dominate the collective psyche. Bangladesh's Muktijhuddo is a case in point--it was a time rife with revolutionary zeal, a Marxist upsurge, many thought, was about to take the East Pakistani society by storm, until the Awami League's nationalist six-point programme shook the very core of East Pakistan and became a rallying cry for the Bengali nationalists. Even though the charter incorporated anti-imperialist policies and called for the emancipation of the masses, it sowed the seeds of a bourgeois democratic revolution, where people of many classes and political affiliations took part. It was a free-for-all situation, an open-ended road: the revolution could have turned socialistic, had the reds led the upsurge and made their guns heard louder, it might have blown into a Viet Cong style guerrilla war where the loss of lives would have been higher. The depiction of individuals in our glorious war of freedom has remained conspicuously absent in our novels. There are quite a few honourable exceptions, of them, most notable perhaps are: 'Nishiddho Loban' by Syed Shamsul Haq, 'Aguner Poroshmoni' by Humayun Ahmed and 'A Golden Age' by Tahmima Anam. Ruby Zaman's debut 'Invisible Line', which is about pain and the price people have to pay for freedom, is the new addition to the list. What sets Ruby's magnum opus apart from its famous predecessors is not its theme, but its characters, which are as diverse as her storyline. It starts in a dark London winter, it is about to snow and Zeb is about to enter the dreary Bangladesh High Commission. The story unfolds slowly and a few short crisp chapters take us back to Chittagong, a melting pot of cultures. The events in the run up to the war catch the protagonist and her upper middle class surroundings completely off guard. The war is about to knock on their doors, and oblivious of its arrival Zeb falls in love with a half-Bengali young man, dreams of a life which would take her to the high plateau of Scotland, and also feels the pang of separation when the love of her life leaves Chittagong and does not write her back. In her portrayal of upper middle-class life in the Chittagong of 1971, Ruby brilliantly depicts late-night parties in the late sixties, the book's omniscient narrator is present everywhere, but like Maugham, she is aloof and thrifty. Read: "Zarina begum's aggressive wooing of socialites expanded to include the elite of Chittagong society. The deputy commissioner's wife was often asked over for a cup of tea and a game of Mahjong. The district judge's wife, the young fashionable wives of army, navy and railway officers stationed at Chittagong, the families of local MPs and the chief medical officer's wife were often invited to a ladies' lunch or high tea."

There are however patches of disturbance, a Bihari man, supportive to the Bengali cause, was lynched because he speaks Urdu and so is thought to be an enemy of the Bengalis. The murder of Biharis during and after the Liberation War has been considered by Bengali writers a taboo topic, and hence a few of them have endeavoured to touch it in their works. Ruby deserves kudos for developing the Bihari's character in a dispassionate way. When the story moves to Sylhet, and as the war breaks out, Zeab's world turns upside down. Majeda Khatun was raped by jawans of the Pakistan army. Zeb's parents are brutally murdered in a train. She was later raped by a gang of Pakistani soldiers. The brutal irony however does not escape us: "She wanted to tell him who her grandfather was, hoping that the name would make the chap realise that he was making a mistake. Mudabbir Ali Khan's entire political career was based on the ideals of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the father of the nation. Raping the granddaughter of such a diehard Pakistani was a gross mistake, she wanted to tell the jawan. But before she could utter a word, she felt a sharp pain inside her body." The story starts to jump time and place and shuttles back and forth from Chittagong and London. 'Invisible Lines' in a way is a journey, Zeb's journey through the maze of war and human relationships. What indeed makes the novel an interesting read is that the story does not revolve around Zeb alone, it is also the story of Shafiq, a valiant Muktijodda who loses a leg in the great war, falls in love with Zeb and ends up marrying a "Punjabi maiden". 'Invisible Lines' is also Didi's story, an enduring presence in the novel, the old woman, who has been in charge of the household, at times towers the other characters, witnessing the turns and tides of time and the labyrinth of love and brutality that we sometimes call life. 'Invisible Lines' is a tour de force, a remarkable début novel. It has all the qualities to become a point of reference for the later writers. It will be interesting to see what Ruby comes up with in her next work; the story of Abdur Rahim, the lynched Bihari perhaps? Or a Robert Musil-like 'The Man without Qualities'? Ahmede Hussain is the Editor of 'The New Anthem" (Tranquebar Press, India, 2009).

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2011 |