| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 33 | August 26, 2011 | |

|

|

Fashion The Bangladesh in Bangladeshi Fashion OLINDA HASSAN

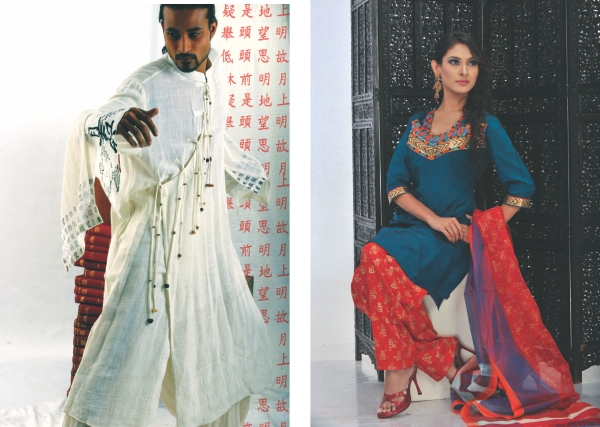

Fashion in Bangladesh is much like the streets of Dhaka. They reflect changing patterns, unexpected colour mix, and is the meeting point of sudden chaos and quiet. It's moody, it's traditional, and it is also in a transition between the old and new. Fashion in Bangladesh doesn't want you to forget its history. As more styles and materials enter the market from the outside however, it can sometimes be difficult to hold onto this Bangladeshi fashion that we speak of. With the demand to look unique, an abundance of new boutiques with distinctive names have started to crowd Dhaka. Designers and fashion houses have begun to fuse influences from abroad and within, creating new lines of work that are meant to be contemporary. Additionally, more from the outside is coming in- Indian katan, Pakistani cottons, Jaipuri colours, South Indian embroidery, etc. The hustle to look exclusive has led to an increase in this demand for foreign clothing and often, foreign styles. Namely, Indian fashion has flourished, not only with its import but also with the rapid copying of designer's items from Mumbai and Delhi. Many boutiques will proudly boast that they only sell imported and thus “exclusive” pieces. While this takes place, we must ask, what then, is the Bangladeshi style? What makes Bangladeshi fashion, Bangladeshi? While clothing from the “outside” is heavily popular, a number of boutique houses have also started to claim clothes and accessories only bearing roots to the homeland, whether that's reflected in the jamdanis, the muslin, cloths bearing prints from local artists, or bringing in tribal motifs from far edges of the country. “When speaking about ethnicity, I fuse tribal with East and West, and I incorporate my own prints, take from the history of Bengal…a huge diversity of culture is used, from languages and scripts and applying typography in my work”, explains Aneela Haque, prominent fashion designer and founder of her line, AnDes. “The uniqueness of Bangladeshi fashion is made through those who decide to deal with Bangladeshi material for designs,” says Khaled Mahmud, Director of the ever expanding Kay Kraft boutiques. Khan describes how in order to discuss what makes Bangladeshi fashion unique, we must talk about the weavers and their handlooms in the country. The blend of traditional weavers and today's designers' inputs has brought together distinctive deshi materials, allowing for more experimentation with hand weaving. Maheen Khan, leading designer and head of her own boutique Mayasir describes how a piece that uses our tradition and our own textiles is what makes it Bangladesh. “Our middle men's work, our cultural intervention, the calligraphy, folk art, Dhaka's jamdani…this is what makes our fashion,” she adds.

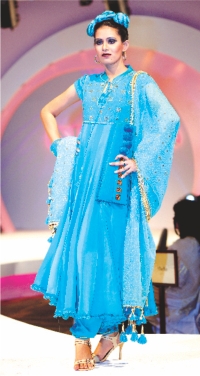

Bangladesh is also famous for its khadi, dating back to the 1930s when Mahatma Ghandhi excited the regional people, advocating wearing clothes from the homeland to express nationalism and an appreciation for tradition. Hand spun cotton thus became popular in Bengal, continuing its wear beyond independence. “Although it has been thought that only the intellectuals wore khadis, I somehow always liked this rugged, uneven, rough textile which is very unique and something that makes you stand on your own…it has that ethnic feeling about your own homeland,” says Aneela who has been inspired by it and uses it along with tribal motifs to contrast Bangladeshi fashion in her line. The way that the clothes are worn, and the way they are cut and composed is equally important in defining and motivating Bangladeshi fashion. “The traditional sari is very symbolic, but only if it can be worn nicely and encompass her as a whole,” expresses Khaled Mahmud who encourages not only the creation of quality saris bearing our roots but wearing them appropriately. Further, while many cuts exist for the shalwar kameez, the Bengal region used to be known more for the long, lean, floating kameez combined with fitted churidar styles, layered heavily at the bottom. While this style has been the rave in Pakistan for some time already, it actually originates from Bengal and has just started to appear this season in Bangladesh. “The churidar makes one look slim, but many won't try it because they are not comfortable in it. I have tried to encourage it with different cuts that are more pant style, and also used a lot of ethnic cuts and straight, long churidars,” says Aneela. Attempts to introduce the long, flowing kameezes both in simple cotton and heavier material with ornamentation, combined with wider ornas has been observed recently, such as at Aarong and Mayasir on the runway.

In the city, you will be struck by vibrant colours and contrasts, along with the more subdued and tame, working together to create the feelings that have defined the urban culture. AnDes for example use very vibrant and solid colours that signify the low paddy fields, the changing blue skies and green fields that plaster the subcontinent. Beads and shells are used in the saris to incorporate the flat lands and the hill side of Chittagong and the seas, and calligraphy from our famed poets who spent time travelling around the country. Designers in Bangladesh have also tried to fit their latest clothing to the current seasonal changes in their colour palettes. Since Eid will fall near the end of the summer this year, fashion houses such as Kay Kraft consider this fact by paying attention to the colour schemes that represent the summer and its rain by incorporating a palette of blue hues and whites to vibrant oranges in their salwar kameezes and cotton saris.

Block prints, hand woven materials and dyes made of ingredients that pay homage to Bangladesh have been gaining prominence among many designers, finding its place on the shelves of many leading boutiques. Aranya's locally produced silk saris in purely natural dyes has continued to attract attention, and it has expanded its collection this season by including more endi cottons and block prints that capture the traditional Bangladesh, especially in their saris. These native elements as integrated by designers work to define the Bangladesh in fashion, among shelves of other South Asian work. Even then, with all the movement for bolstering domestic goods, there is still a strong preference for the outside, such as those from India. Many designers for example will bring in cloth and materials from India and patch them together in Bangladesh, confusing its association- is this Bangladesh that I am wearing, or India? Further, the line between carefully crafted designer fashion and designs that are simply copied in bulk claiming to be boutique also makes it difficult to look for authentic styles. With a partiality for India ever present, the Bangladeshi market in turn is being interrelated and even changed. Thus, sometimes identifying what is the Bangladeshi trend becomes complicated. As fashion moves forward, this question will have to be asked, and it will inevitably be on the minds of designers and buyers. The return of the jamdani saris for example is deeply attached to the tradition of weavers in Bangladesh, albeit the cutting and infusing it with other materials that has appeared recently. “It took a long time to achieve a standard for the jamdani,” said Maheen Khan, however “adding chiffon and embroidery to it and calling it a trend is mutilating the tradition. We should encourage weavers to produce better weaves instead of making a big mess of the jamdani. The weave itself says a thousand words.” Browsing through the many new boutiques, more and more people are purchasing jamdanis, block prints, Banarasi silks, etc. that have been mixed, cut, and contrasted with different materials and styles in an attempt to make it look contemporary and individualised. With this trend, it can be observed that fashion in Bangladesh is not only trying to hold onto its own creative roots, but also finding a way to change it so that they will be worn by those who also want exclusivity. As Bangladesh itself is being increasingly exposed to the outside, it is inevitable that this will come with outside influences, especially with fashion. And fashion is very much alive in Bangladesh, just like the world; it is estimated that people spend over USD$1 trillion per year on fashion worldwide, after all. Fashion extends to everyone, to all generations and economies. As Khaled Mahmud echoes, “We have to use all the techniques of ornamentation available in our country and strategically so that people from a wide range of backgrounds can enjoy our Bangladesh's fashion.” As for today, keeping up with the transitions and an increased focus on just looking good and different does not mean that the modern individual should forgo their own country's fashion, even if mixed and matched, but most importantly, represented. “Every culture has its own heart and for us, if we lose our culture we don't have much left,” points out Maheen Khan.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |

||||||||||||