| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 40 | October 21, 2011 | |

|

|

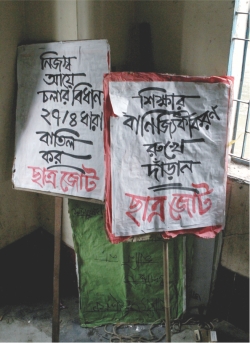

Cover Story Education for Sale? Recent events at JnU have again brought to focus the possible catastrophic consequences of UGC's long term strategic plan for higher education. In addition to multiplying the cost of higher education, the policies will leave research, curriculum and integrity of academic milieu susceptible to corporate intervention. Analysts anticipate that the institutions will have the façade of public universities but will essentially function as private ones. Attempts to implement the policies are being met with strong opposition from the students. Under the circumstances, the authorities need to rethink the contours of the strategic plan. Akram Hosen Mamun Photos: Zahedul I khan The victory The premises of Jagannath University (JnU) on October 9 turned into a festival ground. The rising crescendo of a mob of euphoric students shouting slogans of victory over blasts of firecrackers that sounded like gunshots, gave a loud and clear message. In the carnivalesque air, students' faces were splashed with red hues and their dresses smeared with coloured water. It was not rag day nor was it a commemoration of the just finished Durga Puja. The students were celebrating a victory. They had won the right to university education.

The JnU authorities closed the institution on September 29 following a four-day-long mass protest by students demanding continued government funding for the university. Six days later, the government succumbed to the popular demand and decided to keep subsidising the JnU, Comilla and Kazi Nazrul Islam universities like other public universities, reversing the previous decision to stop funding. It was a great achievement for the protesting students who had demonstrated in the face of brutal oppression by law enforcers and the student wing of the ruling party. The JnU Law, passed in 2005, states that the institution would be financially self-reliant in five years and that the government would stop subsidising it. When the time came for the painful decision to be executed no one was ready for it, especially the students whose dreams of a future were about to be shattered forever. The tenacious resistance of the students and some of their teachers, however, finally won over the government, convincing it to change the law.

The story may seem simple enough but it is an example of how seemingly innocuous policies can have disastrous effects. If we look at the whole phenomenon of cutting subsidies on education and the gradual privatisation of public education system over the decades, we will understand that there is a continuation in the whole process and that global financial organisations are major players in this game. Perhaps the story isn't so simple after all. In 2006, the University Grants Commission (UGC) published its Strategic Plan for Higher Education in Bangladesh: 2006-2026. The contours of the detailed paper were framed by the advice of the World Bank. Among others, it stresses that public universities should increase their internal revenues and become financially self-reliant, enabling the government to cut subsidies. And the two major political parties, despite their many differences, seem to be united in their idea of a financially self-reliant public education system. The plan also proposes the establishment of a number of new universities, the infrastructure of which would be built by the government but they would run with their own sources of revenues. In other words, the envisioned institutions would have the façade of public universities while functioning as private ones. The 'Innovative' Ways The strategic plan stressed that the universities should “generate their own resources” by leasing its buildings, lands, cafes, shops, consultancy services etc to private organisations. The UGC has also seen potential sources of revenue in graduate tax, student insurance, evening courses and alumni associations. Besides its blatant call for multiplying tuition and other fees for the students, the strategy also advocates putting limits on residential facilities for students and has opened up ways for corporate intervention into academic research. “Public universities are different from private ones," says Serajul Islam Choudhury, Professor Emeritus, Dhaka University (DU). "The public universities are a responsibility of the state itself and they depend entirely on state subsidies while the private ones are funded by an individual or a group driven by a profit motive or at least they have to be commercially viable institutions. For public universities, it's not possible to collect the entire fund from their students. So, they need to obtain the rest of their funds from other sources like corporate bodies and the alumni, many of whom are willing to contribute.” He also added that education is the most productive sector. “And despite what we always hear about high government spending on education, I think we should look at the actual spending, the allocation, in percentage terms, of GDP for education. For a country like ours, it should be at least 6 percent of the GDP, as UNICEF suggests,” he says. Even by South Asian standards, Bangladesh's spending on education is meagre. “The policies are a part of a much larger global scheme of the World Bank," says Dr Piash Karim, professor of Economics and Social Sciences at Brac University, "and we should look at the whole phenomenon in relation to the impact it left in other developing societies." Dr Karim comes down heavily on the World Bank, saying the class cleavage deepened, and devastating problems were created in macro economic variables wherever policies suggested by the World Bank were implemented. "It's the responsibility of our government to resist these policies,” he says, adding that privatising public hospitals, schools and other utilities is not a good sign for the economy in the long run. A widely debated source of outside fund for universities around the world constitutes contributions of corporations and big businesses. Analysts have often found that outside funding tends to have preconditions and constraints that affect curriculum and academic research. It is understandable that corporate interest and the goals of education may contradict each other. But the extent to which corporate involvement affects the integrity of the elementary ideals of education demands careful consideration. Therefore, UGC only lends itself to question when it designed and implemented the establishment of “links between the industry, business and higher education institutions in the key areas of research.” The Privatising Effect Academic Freedom and the Corporatization of Universities Noam Chomsky

A visible sign of outside funding are the names and logos of private banks and telecom corporations that one gets to see in the corridors of the “good” departments of DU and JnU. Prof Akmal Hossain of International Relations of DU says that he sees no trouble in taking funds from business organisations “as long as they give it without any preconditions and without any profit motives. I don't want the university to be a site for advertisements.” However, the funding issue has more intricate and subtler effects than a few advertisements on campus. Since corporations are driven by a profit motive, they invest only in the researches and departments that have some market value. In particular, when it comes to academic research, as Chomsky notes, private organisations do not fund projects that would do some public good and leave nothing for corporate profit. To keep in line with market demands, the UGC's strategy also deems departments of literature, philosophy and pure sciences outdated because they have, according to the UGC's strategy plan, “little linkage with the available job market or real life situation”. And higher education is unlikely to reach its goal if it cannot produce graduates according to “the needs of the industries and business at home and abroad”. Hasan Al Zayed, assistant professor at the Department of English at East West University, thinks when big corporations fund universities, they'll obviously take advantage of that, leaving an adverse effect on the integrity of education, research-works and so on.

“You can't expect the corporations to be benevolent institutions. They won't just give away a huge sum of money for the well being of the common people. That's unprecedented in history,” Zayed says, “Besides, letting the big businesses fund universities is against the principle that universities are properties of the common.” Experts, however, find it unbelievable that the government doesn't have enough money in its coffers to run the universities. "Before we receive funding from the corporations, we can try to curb the huge sums that are being wasted through bureaucratic mire and corruption. Stopping those would give us enough to run several universities," Karim says. The market oriented nature of our education can be understood even with a superficial examination of the programmes of any private university in the country. They teach only those subjects that ensure a white collar job for the graduate. Our public universities are also following that route at a pretty fast pace. The trend is not limited, however, only to higher educational institutions. The ever increasing enrolment in the subjects of commerce and a sharp decline in the number of students who take science at SSC and HSC tiers tell us a lot about the turn our education has been taking over the last couple of decades. According to newspaper reports, the percentage of science examinees at the SSC level has dropped to 22.32 in 2010 from 42.21 in 1990. Similarly, at the HSC level the percentage of people who took science subjects was 28.13 in 1990 and that dropped to 18.14 percent in 2010. A Prothom Alo report shows an opposite trend in commerce-centric subjects. As a discipline of education, commerce was introduced into the SSC level in 1996. The number of commerce students who sat for the SSC examination in 2001, was one lakh twenty-nine thousand, but in 2010, it rose dramatically to three lakh fifteen thousand. In percentage terms 16 percent students took commerce subjects in 2001 and that rose to 32 percent in 2010.

Observing the trend, Serajul Islam Choudhury says, “Organisation, administration, recruitment of faculties, selection of subjects, everything is overwhelmed by a wave of commerce that prioritises profit over education.” The gradual metamorphosis of Bangladesh's economy into a market based one has not failed to make its mark on the scenario of education in the country. Rather than production, our major economic activities include the sales and distribution of imported commodities. We have the largest supermarket in South Asia, for instance. As an inevitable consequence, the country needs a lot of white collar workers and clerks who are not related to production, in any serious sense. At present, the education in commerce discipline largely fulfils that demand.

With this much background in mind, the UGC's call for public universities to increase their “internal fund generation” and the “rationalising [of] tuition and other fees” seems like a scheme that will leave a carcass of the already ailing public education system. The Flag of Resistance Flies High Positive changes in the society do not come as a gift from concentrations of power or from people with privilege. Rather, changes are brought about by popular struggle and the sacrifices of countless individuals. “What was about to happen to JnU was an unhealthy transition from a public university to a private university,” says Piash Karim who gives credit to JnU students for their courageous efforts to revert the government's decision. Indeed, the students who took to the streets have shown painstaking dedication and commitment to defend their right to education, which in a functioning democracy would have been accorded to them by law.

However, oppression on students protesting rising tuition fees is not a new phenomenon. The students of Chittagong University suffered an even more brutal attack by the law enforcers while protesting the increase of tuition fees only a year ago. “Had our resistance failed, the students of Jagannath University would have to pay three to six times more as education fees,” said Didarul Alam, a student of Political Science at the JnU, “We are trying to form an inter-university coalition of students who will resist the policies of World Bank and UGC by organising a planned movement. The coalition will accommodate all the spontaneous movements that are being organised in different universities." If “fostering independent thinking and inquiry” in students is what universities are for, it is crucial to keep them state funded and free of any commercial influence. That is not to say we support students going berserk and vandalising vehicles in the street. But if non-violent student demonstrations are constantly rewarded with batons and boots, if dissenters are always met with contemptuous violence, then what lies beyond the bend might not be so pleasant for those in at the helm.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2011 |

|||||||||||

However, the government reacted to their just demands by immediately deploying law enforcers who attacked them with unnecessary brutality. We also remember with horror how Chhatra League Cadres smashed the face of a demonstrator.

However, the government reacted to their just demands by immediately deploying law enforcers who attacked them with unnecessary brutality. We also remember with horror how Chhatra League Cadres smashed the face of a demonstrator.