| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 42 | November 04, 2011 | |

|

|

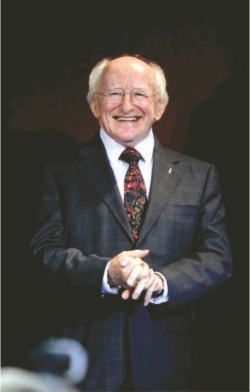

Musings Poetry in the Halls of Power SYED BADRUL AHSAN

The election of Michael D Higgins, the Irish poet, as president of his country cheers the soul. Poetry has that soaring quality about it. It elevates the soul on to a higher plane of experience. And one who writes poetry is capable of bringing forth the best that defines human nature. Of course it was Shelley who informed us that poets were the unacknowledged legislators of the world. We knew they were. What we did not know was putting the thought down in the way Shelley did. Today, with Higgins' election to the presidency of Ireland, we have good cause to celebrate. Something of spring begins to shine in us when we know that a man who has written beautiful, captivating verses all his life has finally ascended to the power which comes of a practice of politics. Higgins' triumph is doubly appealing because of the literary heritage Ireland has historically been heir to. There was William Butler Yeats, to be sure, with all his invocation of Easter 1916 and, yes, with his paeans to the woman he was not destined to share life with. Maud Gonne did not reciprocate his love, but she did egg him on, in that figurative sense of the meaning, into some of the brightest of poetic thoughts in all of literature. Which takes one to remembrances of the American poet-politician Eugene McCarthy. In the late 1960s, McCarthy, then a senator, caused beautiful commotion all across America when he nearly beat President Johnson at the New Hampshire primary and eventually forced LBJ out of the presidency. McCarthy was a true representation of the scholar who could have made a difference had he won the presidency. That did not happen. He got clobbered by Robert Kennedy in the remaining primaries, tried to run for president again some years later. And then he fizzled out. But he did offer hope at a critical moment in American history. Riding an anti-Vietnam war wave, he forced other politicians into speaking of the futility of a conflict that would leave America seared in experience. In Senegal, there was more of a poet than a president in Leopold Sedar Senghor. And yet there came a time when the founder president of the country combined verse with rhetoric to drive a sense of purpose into his people. He governed well. And his poetry touched upon the fundamental values which poets down the generations have consistently dwelt on. You could proffer a similar opinion about Francois Mitterrand. He was not a poet, but in his scholarly insight into life, he made people aware of the power of the word that could go into a rejuvenation of the power of politics. His writings, his ruminations, his observations on life and nature introduced into the Elysee a cultural ambience that has not quite been spotted since he made his way out of the presidency and then out of this world. Mitterrand brought an intellectual flair to his presidency. His difference with John F. Kennedy was that while he was an intellectual himself, JFK was not and yet understood the need for the White House to be transformed into a symbol of all the best that was in American culture. You remember here the poet Robert Frost.

In Victorian Britain, Benjamin Disraeli was the ultimate politician. He was grave; he was witty and he knew of the many ways in which men conducted themselves on earth. And that was a powerful reason why his was also a compelling presence in literature. Politics was his domain and so was the world of fiction he shaped through his novels. But that is not what you can say about Woodrow Wilson. He was no novelist or poet, but he was an academic who added to the glory of Princeton University in the way scholars do. And then he was catapulted to the presidency of the United States, in which position he meant to carve an influential niche for his country through giving a framework to the League of Nations. Congress became an impediment for him. Wilson would die an unhappy man, his presidency not remembered for much in terms of achievement. Now, if you think back on the dissidence Vaclav Havel symbolised in communist Czechoslovakia, you will have cause to wonder why a man instrumental in causing the velvet revolution in his country through his plays and his ruminations on literature was unable to prevent its break-up. Havel, starting off as president of Czechoslovakia, soon found himself president of one half of the country people had begun referring to as the Czech Republic. Slovakia had decided to go its own way. If you have had cause to let your mind dwell on the intellectual lurking in Dag Hammarskjoeld, you will feel the depths which defined his views of life and beyond. Markings remains emblematic of the Hammarskjoeld approach to human experience. And in Mao Zedong was a near perfect balance achieved between the poet and the revolutionary. The Chinese leader was moved by the setting sun and by rising mountains. The contours of the land coursed through his soul. It was geography he would shake up decisively. When he stood at Tienanmen in October 1949 to proclaim the coming of a communist people's republic, it was poetry he found reflected in the gleam of the distant moon, climbing into the sky ever so magically and with verve. Michael D Higgins brings the magic of poetry back into the hallways of political power. There is, therefore, cause to celebrate.

The writer is Executive Editor, The Daily Star.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2011 |