| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 42| October 26, 2012 | |

|

|

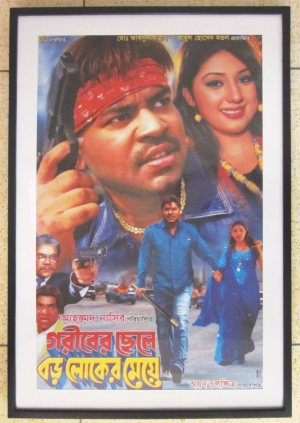

Cinema Impassioned Rage in Civilised Dress Andrew Eagle Art is a window to a culture's soul, so is it any wonder I should have sought out a flagship piece upon moving to Dhaka several years ago? It's daring. It's brash. It's bold. The poster, 'Goriber Chele, Boro Loker Meye' or 'The Poor Family's Son, the Rich Family's Daughter,' in English, is an art piece that is simultaneously undeniably contemporary in outlook and yet without reticence in its clever allusions to tradition. Without doubt a virtuoso accomplishment at the cutting edge of the twenty-first century Bengali nihilist collectivist pop art postmodernist movement, within the post-contextual stream, it is an artwork not to be underestimated. Or at least, without being an art expert per se, that's what I'm thinking. To begin with, in its unusual print-on-paper poster format of bright colours and in its audacious collage arrangement of busy, engaging imagery, 'Goriber Chele' is a work that isn't in need of a polite introduction in order to draw in the attention of the viewer. Rather, it screams to be looked at. That is surely why when carrying it home from the framers by rickshaw people on the street were laughing to see it and calling out their approval. And 'Goriber Chele,' the poster, upon having captured our attention, surely has little potential to disappoint. Not least, the plastering of multiple editions of the work at one time across the city was surely an appeal for artwork for the masses, and as an artistic achievement, even Warhol must have admired it. But what is it exactly that makes 'Goriber Chele' so memorable?

For a start it's in the detail, such as the sunshine in the hair of the woman portrayed in the top right of the piece. With her sunlit hair strands almost reminiscent of freshly cut rice hay, there is clear allusion to the countryside and to nature. The contrast with her unmistakably urban attire, with her make up and hairstyle clearly creatures of the city, is masterful, bringing one to wonder at the conflict between modern, urban living and the natural environment. It is after all within the natural world that our urban lifestyles must continue to exist. And one is led to consider, is it modernity that made her slightly but pleasingly crooked smile or rather the warmth of the sunlight on her hair? Like the Mona Lisa before her, we ask, what is it she is smiling about? Meanwhile her male consort, who the artist Someone-or-Other has chosen as the focal point of the piece, looks intently into the distance, as if to survey the future not only for himself but for her too, and possibly the whole of society. While his gold chain might signify that the present is not too bad, his expression and the fact that he hasn't had time to brush his hair speaks of risk and danger in the coming days and years. Surely Someone-or-Other has made a deliberate decision to not have him look directly into the eye of the viewer, leading us to understand that it is not the current society around him that is of primary concern. Indeed, we are mere distraction. Another subtlety to admire is the angle of the gun he carries. It's pointing skyward in what may well be a further concession to nature. We cannot deny that it's an angle which must be perfect for shooting wild ducks. It's all about survival. Is that the message? Also in the primary images of the man and woman are small yet significant symbols of Bengali culture, in the hand printed pattern of his bandana and in her delicately painted folk jewellery. There can be no question that the artwork here conveys a sense of continuity, that whatever tensions he views in the future, whatever it actually is that is making her smile, the future will regardless occur within a Bengali cultural paradigm. Bangladesh forever is what it says. Bangladesh will survive. Below the primary images, the male and female in the piece are reproduced, this time with the fellow holding a lathi or stick, and the woman in a more distressed state perhaps because her thumb is caught in her hair. The joining of hands here gives purpose and strength to the pair and can it be that the two are battling the crowds and traffic in order to complete their Eid shopping in time? It's an image that's relatable. It's an image that's very much 'now'. And from the blood on his forehead we are given hectic, stressful and even barbaric: the full array of adjectives for the Eid shopping experience. And another question looms unanswered: did they find the right sari for Aunty? An artist of lesser talent may have stopped there, but Someone-or-Other was not content. In the bottom left we meet two other portraits, of a business-suited bespectacled man aiming a pistol and another gentleman in a yellow jacket with a Munch-esque, horrified, shrieking expression, quite possibly conveying the important social message that things don't always go well at the hairdressers'. The pistol-toting gentleman meanwhile wears two rings, like taps in red and blue, hot and cold, which may point to the perennial changing of seasons or perhaps to the coexistence of extremes that we face while living in this mega city. His is a gaze of greater intensity than that of the principal figure; and that expression of rage when combined with his suit and tie once again returns to us the idea of extremes, with impassioned rage in civilised dress, which is, not accidentally, a possible description of Dhaka itself. And what is he aiming at? Well he's almost aiming at us, isn't he? His Dhaka includes and consumes and menaces us too. That's what it says. As if all of that were not enough for us to take in, Someone-or-Other has taken the pains to illustrate the scene of burning cars in the background, which may be a plea for consensus on key issues or it might represent the feelings of enflamed frustration aroused in drivers and passengers while locked in the jam. Perhaps it is up to us to decide which particular interpretation the artist has intended? Lastly, worth mentioning, is the inclusion of the artwork's name in bold, striking font at the bottom left. Here again we must consider the work's pop art foundations and there would seem to be overtures to business marketing in it, to branding and enterprise, a subtle statement that in the environment of the current century, even an artwork of this stature must have a capitalist purpose beyond its perplexing, philosophical array of themes and sub-themes. It is not merely an intellectual feast extraordinaire, but also, almost, some kind of advertisement. It has been a great privilege to have work of quality such as 'Goriber Chele' hanging on the wall at my house for the last several years. It's an art piece that invites critique from all corners, and in particular has brought a warm and welcome smile to some of the tradesmen who have reason to arrive, time to time. And as much as it is a work to be enjoyed everyday, so its value as an investment cannot be overlooked. With an initial purchase price of zero, when the cinema manager first gave it to me, I am convinced a work of such magnitude cannot but appreciate, and must be worth at least three times that amount within the next several years. Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |