| Ekushey Boi Mela

Deprived of their Fair Share

The Ekushey Book Fair, which is now the most anticipated literary event of the country, has begun at the Bangla Academy premises. If the academy and publishers are behind this literary extravaganza, then the writers are at the heart of it. While the fair comes as a blessing for the publishers, the authors are often deprived of their rights.

Rifat Munim

It began simply as a weeklong book fair, sometimes extended for another week, at the Bangla Academy premises. But as the thriving publishing industry was spreading its wings among the readers, such a short time span proved to be highly inadequate. Thus the Amor Ekushey Grontho Mela, which is now the most anticipated literary event of the country, eventually evolved into a month-long book fair. To some, it has become an integral part of our cultural identity taking place in the month of February fostering among the new generation the spirit of nationalism.

|

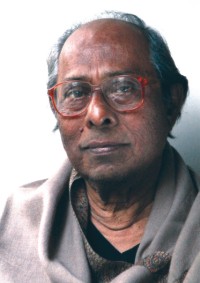

Hasan Azizul Haque

Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

Thousands of new titles hit the fair every year drawing together the young as well as seasoned writers, and a thousand of avid readers and autograph-hunters. Children and grownups alike, swarm to the fair not only with the desire to collect their favourite books, but also with the hope of spending some time with their favourite authors. While walking past a book launching ceremony or for that matter a discussion about the language movement, one would surely feel intrigued to be a part of it. But if the academy and publishers are behind this literary extravaganza, then the writers are at the heart of it. Without the writers' gift of imagination and thought, no book fair would ever have come into existence. While the fair comes as a blessing for the publishers who grab the chance of getting some publicity and making some quick money, what do the writers get?

Some say they get published, some say they earn fame and some say they earn money. Getting just published without money or fame is true for the debutante writers, and earning fame is true for the seasoned ones. Apart from these, all writers, young or seasoned, are entitled to certain rights in terms of special treatment and royalties. It is true that only a handful of highly popular authors receive their due royalties, sometimes even in advance, but royalties for most others remain a far off dream.

Not that authors are craving for their royalties. They are rather quite reluctant about it. Authors constitute the most progressive section of the society, who involve themselves far more with intellectual exercise of all sorts, and far less with the money the publishers owe them. Hasan Azizul Haque, one of the most recognised fiction writers of the two Bengals, says, “It is a writer's responsibility to write. Most writers, in some way or the other, are intellectually oriented. That's why they need a certain kind of serenity to delve into their thoughts. May be that's why they also avoid trivial down-to-earth matters like negotiating their royalties. Eventually they are always at the receiving end of the bargain.”

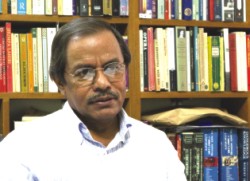

Agreeing with Haque, Syed Manzoorul Islam, professor of English at Dhaka University as well as a seasoned fiction writer of the country, says, “There was a time when the publishing industry was in its infancy. But over the last decade, it has developed into a viable industry. Still, professionalism has not developed in the industry for various reasons.” Shushanta Majumdar, another fiction writer, shares the same plight, but also accuses the newspapers of the same offence.

“Even newspapers do not pay us for publishing our novels and short stories in the glitzy Eid issues. If this is the case with the newspapers, then how can we be hopeful about the publishing houses?”

Most writers, however, when asked about specific publishers who infringe the authors' rights, do not want to mention any specific name, but just point out the practises existing in the sector. However, both Hasan Azizul Haque and Syed Manzoorul Islam admit that there have been some highly responsible publishers who always ensure the authors' right, and without whose dedication the publishing sector would not have come to the stage where it is now. Muktodhara, University Press Limited, Mawla Brothers and Sahitya Prakash are some of the dedicated publishing houses that have been operating with accountability since many years.

|

Syed Manzoorul Islam

Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

The way books are produced, reproduced, distributed and consumed in a capitalist era has come a long way from the old days. In this age, the publishing sector has grown into an industry where people invest to make money. Again, writers are at the heart of this industry, and the publishers merely bank on their merits. It is precisely because of this reason that the issue of royalties has now been universally accepted all over the world as an integral part of Intellectual Property Rights.

Manzurur Rahman, registrar of copyrights which operates under the ministry of cultural affairs, asserts that the Copyright Act 2000 and the amended Copyright Act 2005 very clearly state that when authors, especially those who have not handed over their copyright to the publishers, do not get their royalties, it is an infringement of the author's right. However, the publishers defend themselves by saying that publishing is in no way a lucrative business in Bangladesh. On the contrary, it is in a very sorry state because more and more people are shifting their attention to television and film. But statistics of the rising trend of published books and the gross turnover in the fair contradicts such statements.

According to Murshid Uddin Ahmed, deputy director of Bangla Academy, the fair last year had a turnout of 20 crore taka. But according to a number of authors, the estimate given out by the academy is far less than the real turnover. Ahmed also admits that it is very likely for the publishers to hide the real amount. He assumes the turnover was no less than 50 crore taka. The reasons for faking the real amount are pretty obvious: they want to make the authors believe that sales are poor, so the authors should not talk about their royalties a second time. Because of this surge in sale, production of books has also considerably increased. While a total of 2578 books were produced in 2008, 2741 were produced in 2009. The number further increased to 3354 in 2010, clearly substantiating that both the turnout and turnover in the fair are on the rise.

Osman Goni, executive director of Bangladesh Gyan and Srijanshil Prakashak Samity (Bangladesh Creative Publishers' Association) and also the proprietor of Agami Prakashani, says, “We know there are some irregularities in the sector, especially about royalties and copyright related aspects. But it is true of every sector in the country. I must say things are changing now. A lot of new publishing houses are signing prior agreement with the authors while many are ensuring royalties. I, on behalf of the association, am also trying my best to make everyone aware of a prior agreement.”

|

The Ekushey Boi Mela is the most anticipated literary event of the year. Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

Most of the writers also admit that it has been three or four years since a changing trend emerged thanks to a number of publishing houses including Ittadi, Agami and Shuddhashar.

Prasanta Mridha, a fiction writer from the younger breed of writers, says, “A change is very much visible now. But it has not been more than two years since it started.”

“The main problem is, there is no regulation in the sector, plus there is no responsible distributing agency. This sector must be regularised, and the whole network comprising the publishers, authors and distributors must be expanded,' points Hasan Azizul Haque. Syed Manzoorul Islam thinks that the whole sector is marked by a lack of transparency. He says, “Lack of transparency, in my eyes, is the main crisis of the sector. There is no prior agreement between publishers and authors. That's why even when an author is paid before or after the publication of the book, he knows nothing about the later editions that the book goes through and thus is deprived of his share.” But he also stresses the necessity of an amicable relation between publishers and writers since without the publisher's assistance, many debuting writers would have remained unpublished.

“So writers and publishers should sit together and come to an agreement about how to address all these issues. I think Bangla Academy should come forward and co-ordinate a meeting on the occasion of the ongoing fair,” adds Islam.

Shamsuzzaman Khan, director general of Bangla Academy, says, “We are aware of this. We have received many complaints from writers about publishing houses. Immediately after this we told all the publishers if they do not pay the due royalties to the authors and resolve other problems, we won't allocate them any stall in this fair. While many conformed to our directive, many turned a blind eye.”

Asked about arranging a meeting between publishers and authors, he says, “We have already thought of that. But many publishers have questioned if we are the right authority to address this problem. Whatever they say, I think it is the responsibility of the Academy to ensure the rights of an author. So we are inclined to arrange a meeting after the fair ends.”

It is a highly commendable change that some publishers are already showing interest in prior agreement regarding royalties and other related aspects. Nevertheless, many are still reluctant about it. Despite this, we have to keep in mind that publishers also face many problems especially when it comes to publishing a new author whose works remain unsold for the most part. But with the intervention of Bangla Academy, if a meeting between publishers and writers can be arranged, then it will not be very difficult to bring the whole sector under a regulation and thus ensure the rights of the authors who are the torchbearers of the country.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |

|