Personality

Inside the Mind of a Master Painter

Fayza Haq

Rafiqun Nabi, a well beloved teacher of the Faculty of Arts, DU, is famous for his brushwork both at home and abroad. With silvery wavy hair, and twinkling eyes behind the glinting glasses, sitting cozy on a winter weekend at the Bengal Café, Dhanmondi, he dwelt on visual art in general. Spicing his words with humour and careful observations, his words ran out like some flowing, cascading river. “I like both painting and printing. Painting is my main subject, which I was introduced to at the outset. When I want to change the media a bit, I go in for printmaking. I did printing before I went to Greece on a Greek scholarship. At the the 'Charukola', I sat at the feet of Safiuddin Ahmed (mainly), Habibur Rahman, and Mohammed Kibria.” R Nabi's teacher in Greece was called Grammatopoulos. What he did here in printmaking was basic. They worked with a sharp tool on the wood. The students also learnt etching on metal with acid. Later on his professor taught him woodcut on a large scale. This was also done cutting away on wood with a sharp chisel. In Dhaka the art student s went from light shade to dark, while in Greece they followed the reverse way.

|

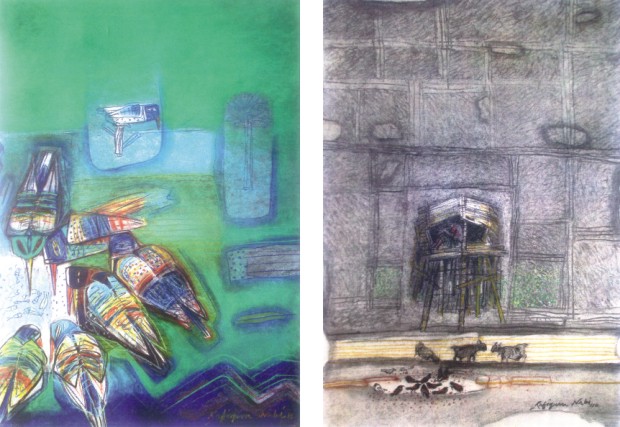

Drawing 8, pastel on paper. Photos: Courtesy |

Drawing 14, mixed mediums on paper. Photos: Courtesy |

His deep compassion for the underprivileged and disappointment at the growing gap between the rich and poor resulted in the creation of the “Tokai” cartoons, for which he became so famous and which created his other identity as Ranabi. He' d gone on to present his ideas with a large measure of humour in his cartoons–so that his viewers could relish them as well as be provoked by them.

How did Nabi get into cartoons? As a student till the mid 6os, there were socio-economic and political upheavals, says Nabi. At that time he used to make cartoons for the processions in the form of direct sketches. Later on printed placards followed. The earlier forms were like doodles. After the Liberation War, and having studied at Greece in printmaking, journalists in “Bichitra “ asked him to continue his cartoons. He then began his cartoon strips in pen-and-ink, commenting on the socio-economic and political scenario around him. In them Nabi brought in serious ideas in a nutshell, as he explains. The messages were simple so that ordnary people could relate to them.

Speaking on why the art world in Bangladesh till the 21st century has not produced something like the old masters of Bangladesh such as Zainul Abedin, Quamrul Hassan, SM Sultan and Safiuddin Ahmed: Have they left behind a following of patience and passion equal to theirs ? To this R Nabi says, “Being maestros cannot be at one's bidding. The environment, the perseverance, socio-economic and political ambiance all go to make the artists. The passion, pain and ability along with many other factors go into the making of a master painter. The vision and the talent are different. Otherwise we'd all be Zainul Abedins. Every artist has the potential to be unique and outstanding. Much depends on the opportunities and timing apart from luck. There are many elements that go into the making of a master artist. Not all poets are of the measure of Rabindranath Tagore. Similarly not all poets can be of the stature of Jiban Ananda Das or Michael Modhushon Dutt or even Shamsur Rahman.”

The master painter also dwelt on what an ideal piece of art must aim at to capture the pulse and rhythm of the people around the artist, or in the mind of the artist – or should the artist please the viewers\ critiques , as he/she must sustain himself\herself and make a living? Do the best of artists have soul-pitch in their work “ The creative artist,” says Nabi “must follow his inner urge. The agony and ecstasy of the contemporary life around the artist must be portrayed. The urge to paint should come from deep within.

|

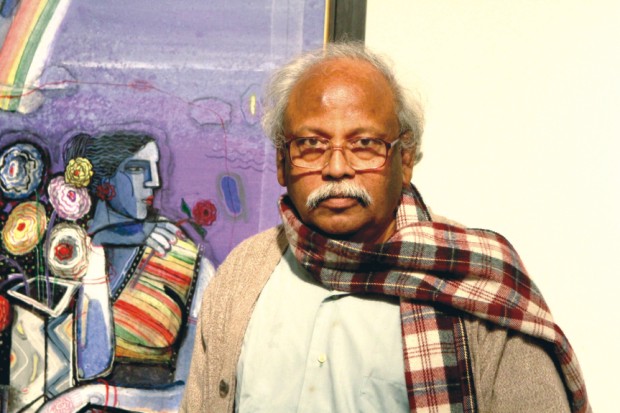

Rafiqun Nabi Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

To just paint is mot a big achievement by itself: What the painting draws out aesthetically–aesthetically or content-wise: The artist selects from hundreds of things around him. The manner in which this is executed depends on his inner drive.”

Would he say that great art is created even out of discontentment and disharmony of mind – as during floods, famines and warfare? To this, Nabi says, “Creative art is not necessarily out of pain. Pleasure too lead to unsurpassed paintings – like Zainul 's Shantal women, gently making their way, or Quamrul Hassan's wives on the river banks, SM Sultan's harvesting or fishing scenes – can bring in art at its best. There is no format for perfect paintings. Tagore grew up in a peaceful atmosphere. He had no economic restraints. If one sees a reverse scene, as in the case of Vincent Van Gogh or Michael Angelo, out of pain came unparalleled art. The early life of many artists have been with sweat and toil. However, there is no ready formula to success and fame. It happens. One doesn't know quite how.”

|

Drawing 17, water colour on paper. Photos: Courtesy |

To whom does he owe his success? What exactly was the backdrop, which helped him form his reputation, skill and personality – which is always mixed and mingled with joie de vivre and ready wit – What was his inspiration and guidance? “ Family background should be there to groom an individual, to encourage a person. My family members, especially my father, Rashidun Nabi, who drew and painted as his hobby. He was a police officer by profession, but he always kept this up. For many reasons he couldn't be a full time, trained artist himself. With his inspiration and support of my mother, Anwara Begum, it was natural that my brothers Rezaun Nabi – who is also a painter, and Shafiqun Nabi a poet and I, the eldest in our family, should go in for something creative–aiming at being significant and unusual. My parents had artistic sensibilities being passionately fond of music and drawing. My father had a large collection of records at that time, in Old Dhaka. Our earlier days were in the district areas, where our father was posted. The ambiance, in our home, always encouraged creative work among us children,” says Nabi. “If one doesn't get family support, to be an artists is difficult,” says the master painter and print-maker.

Not only did he have an inductive family background – all around him egged him on, he says. Among the artists whom he had the opportunity to know and be guided and encouraged by were the most popular and reputed master painters , beginning with Zainul Abedin. Moreover, there were the finest of our artists like Safiduddin Ahmed, Quamrul Hassan, and Habibur Rahman. Along with them, young teachers at that time – but major artists today – like Aminul Islam,Kazi Abdul Baset, Rashid Chowdhury and Abdur Razzaque , Mustafa Manwar were there too in his time. Nabi says that he was fortunate to have had the cream of Bangladeshi artists to mould him. What more could one have asked for?

|

Drawing 17, water colour on paper. Photos: Courtesy |

R Nabi adds that before his having his father to egg him on, coming across superb teachers to guide him, he had been fortunate to have had behind him the array of famed artists of India . These included, he says Abanindranath Takhur, Nanda Lal Bosu, Ramkinkor Beij and Rabindranath Tagore. “European artists and fine art work of the Far East, like China and Japan, also spurred us on,” he adds, “We wondered at their lines and colours, and naturally hoped to emulate their quality of work, some time in life.”

With the highest of the nation's civic awards behind him, and international accolades rewarding his endeavours, Rafiqun Nabi remains one of our finest of visual artists. He remains a highly gifted, self-effacing, warm and wonderful personality of our times.

|

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |