Economy

Share Market Bubble

The Big Picture

JYOTI RAHMAN

In the three years ending in January 2009, share prices in Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE) rose by about 60 percent. Over the course of the following year, it doubled. Initially, this was taken as a sign of justified optimism in Bangladesh's strong economic fundamentals and perhaps not-so-justified confidence in political stability.

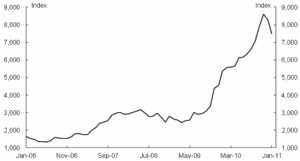

But as early as the first quarter of 2010, a few voices were wondering whether DSE was in the bubble territory.1 These Cassandras were, however, generally ignored. Between January and November of last year, share prices rose by 60 percent. Then in December, the market started wobbling. And in the first few weeks of 2011, it has seen unprecedented volatility.2 Chart 1 shows the DSE prices over the past five year.

That we witnessed a major bubble is now beyond dispute.3 Incredulous investors and an irresponsible Securities and Exchange Commission played major roles in blowing the bubble. But the market participants and their regulators didn't operate in a vacuum. The bubble was possible because we were in an 'easy money' environment – Bangladesh Bank had been pursuing an expansionary monetary policy, and there were too much money chasing too few shares. And the political realities impeded a 'soft landing' – even after the bubble became clearly identifiable, policymakers lacked the willpower to act lest 1996 was repeated.

Easy money

Let's take the easy money first.

Chart 1: Prices in Dhaka Stock Exchange |

|

There is a general consensus amongst the business sector, the government and independent analysts that an investment boom is needed if Bangladesh's economy is to grow by 7-8 percent a year. That's why, even during the periods of high inflation, the Bangladesh Bank has sought to support investment through an accommodative monetary policy. However, in recent years, broad money has been constantly growing faster than the Bangladesh Bank's accommodative targets (Chart 2).

| Chart 2: Growth in broad money |

|

This has happened because of an unintended consequence of the Bank's exchange rate policy. In addition to supporting investment through loose money supply, the Bank has pegged taka against the dollar to support exports. As the dollar has depreciated in the past couple of years, taka has seen appreciation pressures. According to one analyst, had it not been for the Bank's intervention, taka would have appreciated to 60 per dollar.4 The cost of keeping the taka undervalued has been the excess growth in money supply.

Did the bank achieve its objective of supporting investment and export? According to international agencies such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, both export and investment are expected to grow strongly in the coming years.

However, it's not clear whether monetary or exchange rate policies have anything to do with the outlook. Even though the nominal exchange rate remains undervalued, taka has seen a real appreciation against major trading partners because Bangladesh has experienced faster inflation (itself a consequence of the loose monetary policy). Meanwhile, how much of the monetary expansion has ended up in productive investment remains an open question. In fact, there is no reason to believe that investment has been constrained by a lack of finance – one could argue that infrastructure bottleneck, energy shortage, and poor economic governance are important impediments to investment that monetary policy is unable to solve.

|

Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

Rather, what seems to be reasonably clear is that the excess money supply ended up in the stock market. As the appreciation pressure mounted on taka, money growth exceeded the target rate by ever-faster pace since late 2009. A large proportion of that extra money found its way to the stock market. With no commensurate rise in the supply of shares, increased turnover meant rapidly increased share prices.

Thus, in a misguided effort to boost investment and exports, the Bangladesh Bank ended up blowing the mother of all bubbles. The central bank is as culpable for the current mess as any myopic investor or irregular regulator.

The monetary authority was not alone in the well-intentioned, but ultimately futile, attempt to boost investment. The fiscal authority – that is, the government – through tax breaks and schemes allowing whitening of black money, also fuelled the stock market bubble. And in addition, if not for the government's dithering, the bubble could have nipped much earlier.

Once bitten

Underlying the macro and microeconomic policy mistakes have been the political economic reality of the Awami League government's bitter memory of the 1996 crash.

In the second half of that year, the DSE increased three-folds as non-professional retail investors and a huge influx of funds chased a handful of stocks. Then the bubble burst, with the prices collapsing by about 70 percent in the first four months of 1997. The boom and bust enriched a few traders and market manipulators who had knowledge and inside information, while general investors paid heavily.

And most importantly, that experience seems to have made the current government determined to avoid a repetition of 1996.

One might have thought that the best way of avoiding the repetition of 1996 would have been to prevent the rapid run up in stock prices that were witnessed in the monsoon and autumn of 2010. Had the SEC or the Bangladesh Bank stood firm then, perhaps a 'soft landing' – a moderate fall in stock prices followed by a period of market stability – could have been achieved.

But any fall in prices would have left some people worse off. And the government, it appears, was not ready to accept that. Every session of fall in share price was followed by thuggish behaviour in Motijheel, and caving in by the SEC. But without the expressed support of the top econocrats, it's not surprising that the micro regulators of the SEC lacked the stomach to allow market correction.

Unfortunately, just as in politics so in economics, where moderate reforms are impossible, violent revolutions are all but inevitable. By the beginning of the year, as Bangladesh Bank realised that it could no longer avoid monetary tightening, stock prices begun to tumble. Remarkably, even at this late stage, our economic policymakers remained determined to avoid the much needed market correction. Possibly driven by the government's political imperatives, Bangladesh Bank directly intervened in the stock market while state owned banks were allegedly pressured to provide artificial support – the result was the 15 percent rebound in the market on 11 January.5

It is said that people don't learn from history. That's not always correct. People do learn from history, it's just that often they learn the wrong lesson. From 1996, Awami League's econocrats learnt that a stock market crash is something to be avoided. Ironically, they didn't learn how it can be avoided. Now that the bubble has burst, how the country's economic managers steer the country's economy remains to be seen.

Jyoti Rahman is an applied macroeconomist and a member of Drishtipat Writers' Collective.

1. Articles expressing concerns about a bubble in the DSE include: Ahsan Mansur and Nurul Hoque, Stock Market: A ticking bomb, Financial Express, 19 February 2010; and Jyoti Rahman, The Share Market Bubble, Forum, April 2010.

2. For a good summary of recent developments, please see: Raisa Aantaki, Behind the Scenes the Stock Market Saga, The Star Magazine, 21 January 2011.

3. See here: Jyoti Rahman and Shaheen Islam, Myopic Investors and Irregular Regulators, The Star Magazine, 21 January 2011.

4. See: MA Taslim, Intervention, Missing Money and Inflation, BDnews24, 12 November 2010.

5. See: Inam Ahmed, Magic game, once again, 12 January 2011.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |