Dismay overshadows jute sector reforms

It is a Friday and thus, the usual hat-bazar (market) is not in full swing. Yet a few farmers have gathered at the Tekerhut jute market on the bank of river Kumar in Madaripur.

Filled with excitement, we entered the market. Over the past few years, news, features and a number of photo stories have depicted jute farmers as miserable and ragged beings with stooped shoulders and shrouded eyes. Due to the lack of work, they are facing hapless situations, as most of these items had reported. In order to understand the reality behind the accounts, I have been on the lookout for one who can share about his experiences as a jute farmer with me.

The bazaar is more or less empty. Buyers, both from the private and public sectors, are lazily preparing raw jute for sale. After a couple of hours of roaming around the market, I meet Selim Miah, a jute farmer. He doesn't look like any of the images I have seen in the papers. Of standard height and in his forties, he looks quite robust, effortlessly carrying a huge bundle of raw jute, a sign of where the industry can go.

Selim is waiting outside a private purchase centre to collect his dues. He is worried. This year the price list decided by the government was surprisingly low. "Our profit margin is very low," says Selim sadly. Moreover, the abnormal weather conditions led to a water supply crisis across the jute cultivation areas of the country. This mostly affects small farmers who fail to meet the desired production. Because of the dry climate, jute farmers have to irrigate the dry lands, drastically raising production costs. With despair and hopelessness hanging over their heads, jute farmers have despondently termed 2016 as "a year of dry months and bare pockets." Many of the farmers have not been able to sell even the raw jute since the price offered by the government was extremely low. As Selim puts it, "The small traders were also quoting very low prices." Selim fears drastic losses this year.

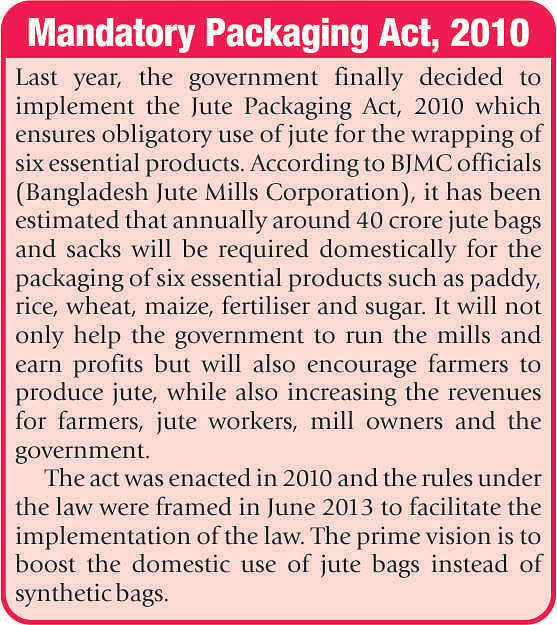

The government came up with a remarkable law in 2010 called the "Mandatory Packaging Act 2010", which is aimed at elevating the production and encourage root level farmers like Selim. The law stipulates the use of jute in wrapping six essential products, thus significantly hiking up the demand. However in the absence of proper monitoring, traders continue to use polythene bags instead of jute bags in packaging their products. Due to the slow consumption in the local industry, the jute sector has to depend entirely on exports; at present only three-fourths of the domestically produced jute is exported. The trend in the local jute sector is affecting jute farmers.

Humayun Khaled, chairman of the Bangladesh Jute Mills Corporation (BJMC), said that the drive needs to be strategic. "The Government should run the campaign quickly to get efficient results," he says. He also stresses that if the law is implemented properly, more than 50 percent of jute products would be consumed locally. He adds that reopening closed mills would not be advisable as excess supply in an already floundering market could create further problems.

The law, if made effective, can bring back the golden days of the golden fibre. But the jute industry is in urgent need of proper monitoring from trading to the production sector and finally, the exporting world.

Still left in the cold

During the retting (soaking jute in water to soften the fibres) time, Selim Miah and his three children carries bundles of jute and walk a long way in search of water. River Kumar is far away from his home. Also, the road to the river is not suitable for the movement of any vehicle.

Another farmer, Mintu Sarkar, accompanies Selim. "It is not an easy task," says Selim. "We have to walk since we cannot afford a van to carry our jute to the river," he adds while saying that it may be easier to write and read about the difficulties faced by jute farmers. "But their reality is much more difficult than meets the eye," says Sarker.

After the revival of the jute industry in 2009, the government has been buying jute from traders on credit as the mills were not able to pay immediate cash for the procurements. Muhammed Tipu, the owner of a jute storehouse informs us that during the golden period in the sixties and early seventies, the government would provide money to public purchase centres to directly buy jute from the farmers. "But now the farmers sell to the middleman at a low price," says Tipu.

Along with the farmers, the jute industry too is riding a parallel storm. The next morning, we arrived at the Khalishpur Jute Mills in the remote areas of Khulna.

Surprisingly before we entered the main industrial area, we heard a faint rhythmic sound. The factory has already begun its day's work. The red-bricked buildings are bustling with production. The closer we get to the factory, the louder the sound grows.

Giant machines are running busily, refining and polishing the raw jute. You'd think that the jute industry is undergoing a boost in its production and profits by the look of the activities inside the mills. However, the reality of the industry is very different.

Around early 2014, 20 jute mills were shut down due to a slump in the international market. But the mill we are in gives a different picture than statistics would have us believe. All the looms are running rhythmically and workers are rushing with jute from one machine to the other.

When the workers realize that we are journalists and here to interview them, a young man named Manik approaches us, asking shyly, "Do you think it would help us if you write about us?" This is a frequent question that we face during our four-day long journey from Khulna to Madaripur and Gopalganj. We don't have the answer.

Pangs of the jute weavers

The public sector has more problems than we had assumed. Manik shows sacks of jute piled up in the factory. Storage rooms in the mill are stocked, ready to sell products. We learn that the fall of international exports is seriously hampering the jute industry. Due to the fall in exports, the weavers are concerned about their jobs and bogged down by insecurity.

On the other hand, even the farmers, supplying the raw jute, are not getting good prices. Robiul Hossain, a middle-aged weaver at Khalishpur Jute Mill, doesn't know about the slump in the international market but he fears that the jute mills might shut down soon. During the last Ramadan, the weavers only got a bonus as mill authorities couldn't pay their salaries on time. 'No work, no pay' - that was the deal between the weavers and the government. "We are afraid of being jobless again," says Hossain.

He is worried about his children and family. He lives on the other side of the river Bhoirob. Every day he rides a cycle to work. Robiul, like thousands of weavers, lived in a government-allotted weavers' residence before. "But when the factory reopened the government didn't allot places for us to live in," he says. The living cost is rising but the necessary facilities that they need to survive are absent.

Before Khalishpur Jute Mills began its operation, there was an unspoken agreement that as the weavers would be doing their job under the 'no work, no pay' rule, the factory would perform well to garner the highest income for its weavers. Thus, the government need not provide weavers with other facilities offered to employees of other factories. Despite such 'savings' the factory is not making the profits that it was supposed to.

While the officials at Khalishpur Jute Mills blame the inefficiency of the weavers in terms of working hours and the pointless unrest carried out by labour unions, weavers claim that the production is not at its maximum due to the corrupt and inept management.

During Ramadan last year, a messy situation was created through weavers' protests and labour unrest, claims GAM Mahbubur Rashid Zulfiqar, administration manager of Khalishpur Jute Mills. "If the weavers don't do their job honestly the situation is not going to change," he claims.

The rise of the jute industry depends on the international market, and new and attractive jute made products, apart from the reformation of factory management and the proper implementation of the Mandatory Packaging Act, 2010.

There are many allegations against the government, owners and even the weavers of the jute industry. If we only take Khalishpur Jute Mills as an example, we can see that the weavers are not happy with the treatment that they are receiving from the government. The pile up of jute products waiting in storage is creating tension and insecurity. Moreover, the facilities provided to them are not enough to support their familes. Manik's family consists of four people. He gets a wage of Tk 1,800 per week. "Do you think anyone can feel any kind of motivation after being paid such poor wages?" he asks.

During the Ramadan last year, a messy situation was created due to workers' protests and labour unrest, claims GAM Mahbubur Rashid Zulfiqar, administration manager of Khalishpur Jute Mills. "If the workers don't do their job honestly the situation is not going to change," he claims.

The rise of the jute industry depends on the international market, and new and attractive jute made products, apart from the reformation of factory management and the proper implementation of the Mandatory Packaging Act, 2010.

There are many allegations against the government, owners and even the workers of the jute industry. If we only take Khalishpur Jute Mills as an example, we can see that the workers are not happy with the treatment that they are receiving from the government. The pile up of jute products waiting in storage is creating tension and insecurity. Moreover, the facilities provided to them are not enough to support their family. Manik's family consists of four people. He gets a wage of Tk 1800 per week. "Do you think anyone could feel any kind of motivation after being paid such poor wages?" he asks.

We spoke to 20 jute mill weavers and all of them had some complaint or the other with the current state of affairs. The production rate is decreasing everyday and weavers are losing their jobs at a rapid pace. The mill officers, however, are permanent employees and thus are provided with all the facilities from the government. Weavers complain that even though they work three times as hard as the officers, it's the officers who enjoy all the facilities. "We don't have any place where the weavers and their families can live. We are living in misery. But the officers are reaping all the benefits, starting from an apartment provided by the government to good salaries," says Manik.

About thirty million people are directly or indirectly involved with the jute industry in the country. At the moment the biggest challenge is to sustain the employment and encourage the farmers. Jute has all the potential to contribute to our economy and it can only be revived if the government is proactive and gradually enforces the Mandatory Packaging Act, 2010.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments