Only good governance can ensure long-term energy security

Bangladesh has been struggling with primary energy supply since 2007, a long 17 years. Unfortunately, the focus was never to solve this fundamental problem sustainably but to build more power plants that are visible and carry larger political mileage. The initial rush of building generation units was somewhat justified and was reasonably successful in providing electricity but the negligence of the primary energy problem has finally caught up. The import-heavy solution of providing primary energy was always risky, expensive, and unsustainable, without a strong economy. Even with a substantial generation capacity, the country is now facing a fuel shortage, as well as a very costly power scarcity. Achieving complete energy independence is unattainable, but for a developing country minimising import always ensures more security. And exploring and exhausting the full indigenous potential will make the country resilient.

Bangladesh was once dependent on gas only. Energy security via fuel diversification required its coal and renewable resources to be exploited. Once the gas shortage started, the mindset of Petrobangla was to explore and exploit our untapped resources. Reviewing old presentations and reports of Petrobangla during 2007-09, it is clear that they understood the gravity of the gas shortage problem, and their projection of gas shortage and demand growth up to 2025 matched the current situation. In a presentation for the 2008 offshore PSC bidding, the agency projected a supply of 3,267 mmcfd from existing international oil companies (IOC) and Petrobangla fields against a projected demand of 3,070 mmcfd in 2014. Out of that total, 1,757 mmcfd was supposed to come from Petrobangla fields. While IOCs ramped up their production, Petrobangla came up short. The idea of LNG import along with the previously stated gas field development plan was presented in the government document of Energy Scenario of Bangladesh 2010-2011. Gradually, the entire development plan was abandoned and Petrobangla decided to supply the gas deficit by importing LNG only. By 2032 it planned to import 4,000 mmcfd of LNG.

The other two indigenous resources—coal and renewables did not get serious consideration in the early years of the fuel shortage. Before all the debate regarding coal, the National Energy Policy 1996 strongly suggested developing coal but it has been kept in cold storage principally for political reasons. Renewable energy got lukewarm support completely depending on the private sector without addressing the real issues. Even today, the objective is confusing. Whether the stated 40 percent target by 2041 is going to come from renewable or clean energy is not clear. On the other hand, there is a big difference between installed capacity and energy produced.

Various plans and agencies state different objectives. The Eighth Five-Year Plan states the addition of 3,700 MW of renewable energy by 2025, Delta Plan 2100 talks about a minimum of adding 30 percent renewables by 2041, Mujib Climate Prosperity Plan 2022-2041, which is the newest plan, states to achieve 30 percent renewable energy by 2030 and 40 percent by 2041. On the other hand, the Power System Master Plan (PSMP) 2016 and Perspective Plan 2021 did not have any scope for renewables by 2041 although they provided a 10 percent and 20 percent alternate renewable scenario. The new Integrated Energy and Power Master Plan (IEPMP) is cautiously optimistic on both onshore and offshore wind although their projection or plan for 2041 is not very favourable to solar power. As a result, researchers, investors, and policymakers get confused and pick up the numbers they like. Climate and environmental activists set lofty goals further puzzling the general people.

Energy security in every country is an integral part of national security. The USA, the Soviet Union, and Europe have fought several wars over energy to ensure national and regional energy security. For such a critical sector, proper governance is the single most key driving force. Political whims or lobbyists cannot dictate the policy. Only energy governance with clear policy transparency can ensure security for the people. Unfortunately, the political economy dominated this sector instead of technical leadership. For example, Petrobangla, the agency responsible for providing energy for the country, was never led by a petroleum geologist or a petroleum engineer.

Managing the gas reserves is a highly technical issue. The intricacy of the structure and fluid deposition under the ground require extensive modelling along with field data for developing and producing hydrocarbon. While Chevron is producing 1,300 mmcfd gas from a remaining reserve of less than 1 tcf, Petrobangla is struggling to maintain 800 mmcfd production from a 7 tcf remaining reserve under its operation. While everyone talks about the exploration wing BAPEX, Petrobangla itself abandoned the idea of exploiting its resources and took the easy path of import. Weak and uninformed leadership was unable to convince the government to do otherwise. Ministry intervention stopped the transparently conducted offshore seismic survey effort twice for completely unknown reasons. The Schlumberger study of gas field development in 2011, that demonstrated how to increase production from the Petrobangla fields, was ignored for years. In contrast to the energy sector, the power sector led by engineers did much better in field performance although some decisions were politically influenced.

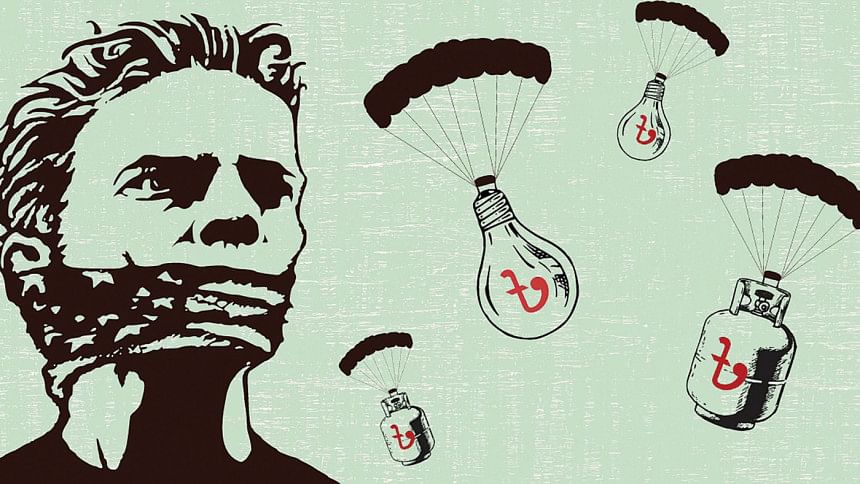

Strong and independent regulation can protect both businesses and consumers. Energy pricing has always been a contentious issue in Bangladesh. Every time oil, gas, and electricity prices increase, people hear about international price increases. Even then, there is no transparency in the rationale behind the increase. When the power of determining gas and electricity tariffs was taken away from the Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission (BERC), the last hope of consumer justice was taken away. This single act exposed the weakness of energy governance. The arbitrary oil price increase on August 5, 2022, triggered the highest inflation in recent time in Bangladesh. A BERC hearing could avoid such rash decisions. The Bangladesh Petroleum Corporation (BPC) cries every time it loses a penny, but it did not mention its 40,000-crore profit during seven years of low oil prices before 2020 or the 4,000-crore net profit it made after the latest price hike. It is the most non-transparent agency of the government.

Similarly, the gas price increase was promised on steady supply to the industry accommodating LNG price but failed to deliver. The BERC hearing at least forced some accountability and transparency of the utilities of their activities and efficiency. BERC is successfully fixing LPG prices every month based on different variable factors including import cost which refutes the government's claim of its ineffectiveness. Tariff determination by BERC has no bearing on government decisions on subsidies. A transparent tariff and subsequent subsidy would help the government in disseminating proper information. Distorted information creates market inefficiency causing suffering for the consumers.

During the 2001-06 period, hardly any generation was added to the grid. There was not even a project on the ground.

As a result, the country suffered a severe power shortage. The idea of oil-based rental power by the outgoing government was taken up by the caretaker government and 10 contracts were awarded through competitive bidding. These contracts comprised a capacity payment and fuel cost, a model borrowed from the international rental business. The oil-based generation units are small and meant to serve the peak load but an 80 percent take or pay condition was agreed upon. This was a big mistake. A machine meant for a short run cannot be used 80 percent of the time. The highest plant load factor for these rental plants was 60 percent which is very high for a peak load operation. The average was 40 percent and some diesel plants were less than 10 percent. Instead of capacity payment, the contracts should have been on an energy payment basis. Even with a higher tariff, it would be cheaper in the long run. Enough homework and examination of these contracts were not done mainly due to a scarcity of experienced energy contract lawyers or hurried decision-making.

The first set of rental power plants did not improve the load-shedding situation significantly. After one year of indecision, the newly elected government had to embrace the idea of expanding the oil-based short-term contracts following the previous model. Because of the urgency of the situation the government enacted the Quick Enhancement of Electricity and Energy Supply (Special Provision) Act 2010 allowing unsolicited offers for all areas of energy and power. It gave indemnity to all involved in the contract award process. Initially, the act was used to award quick contracts for the oil-based rental plants on a war footing which was perhaps justified but by 2012, the load shedding situation improved significantly. In a true sense, the original purpose of the Act was served and should have been scrapped but it was extended several times and is still active. A project that needs to be finished in six months may avoid the tender process in a warlike situation, but on the other hand, avoiding the tender process for a three to five-year long project cannot be justified. Every project awarded under this act without tender after 2014 has raised the energy governance issue.

Without fair, transparent, accountable energy governance and input from knowledgeable technical leadership, long-term sustainable solutions to energy problems in this critical transition period are not possible. A pure political agenda may sometimes create counterintuitive effects. The great Solar Home System success story of Bangladesh was essentially killed when 99 percent of the population was brought under grid coverage. The future of Bangladesh's renewable power trajectory may lie in a distributed off-grid system making some part of the grid redundant.

We are marred with short-term firefighting all the time but sustainable security requires mid- and long-term parallel preparation. A good fuel mix from diverse sources protects a country from both price and supply shock. The current high energy price is more an exception than the norm which will pass away. The existing coal, gas, and nuclear mix will have a lifespan of 20 to 30 years. All completed and in progress coal projects and the nuclear plants comprise 12 GW of baseload power. We have approximately 8 GW of relatively new gas plants that can be used to serve the intermediate load and some peak load. We may need some oil-fired power plants for the peak load but the majority of oil plants must be terminated and the remaining ones need to be contracted on an energy purchase basis.

The missing elements are renewable energy and energy efficiency along with demand-side management. The 600 MW daytime solar can be easily tripled by 2030. The current load curve and the grid readiness can perhaps accommodate 3 GW daytime solar which will save a considerable amount of fossil fuel. By 2030, solar with battery storage will be the cheapest power option but large-scale worldwide deployment may cause a material crunch. The development of hydrogen and ammonia is still in the early stage and its use is limited. A thorough and careful study considering cost, technology, finance, manpower, etc. must be carried out for future energy transition.

Not a single net-zero scenario is without emphasis on energy efficiency. Most of them attribute 20-25 percent emission reduction to efficiency improvement. Bangladesh must take every initiative to increase energy efficiency, especially for fans, air conditioners, appliances, and lighting in the domestic sector along with industry and power generation. Separate summer and winter office time, staggered holidays, limited shopping hours, time of the day metering, and other demand side management measures will help conserve energy and also shift the evening load to daytime. Last but not least, the demand projection for Bangladesh must be reviewed and revised. Sixty GW peak demand requirement in 2041 is based on lofty ambition and numerous uncertainties. The country cannot afford an overcapacity based on a wrong demand projection.

Without good energy governance, sustainable development cannot be achieved. Cronyism and political lobbying will always distort the market discouraging investment. Any policy must be developed through proper consultation with the stakeholders without any political or business influence. The International Chamber of Commerce identified "stable regulatory frameworks to attract energy investment and manage the long-term transition to secure and sustainable global energy systems." Bangladesh must also be in tune with international energy governance taking the right direction.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments