Novera, pioneer of progressiveness in Bangladesh

Pioneer of Bangladesh’s modern sculpture as well as the forerunner of contemporary women emancipation in the country, Novera Ahmed is a name that has worn away in seclusion.

Her potential was recognised by none other than Shilpacharya Jainul Abedin, who wrote that “it will take us a long time to understand what Novera is doing here”.

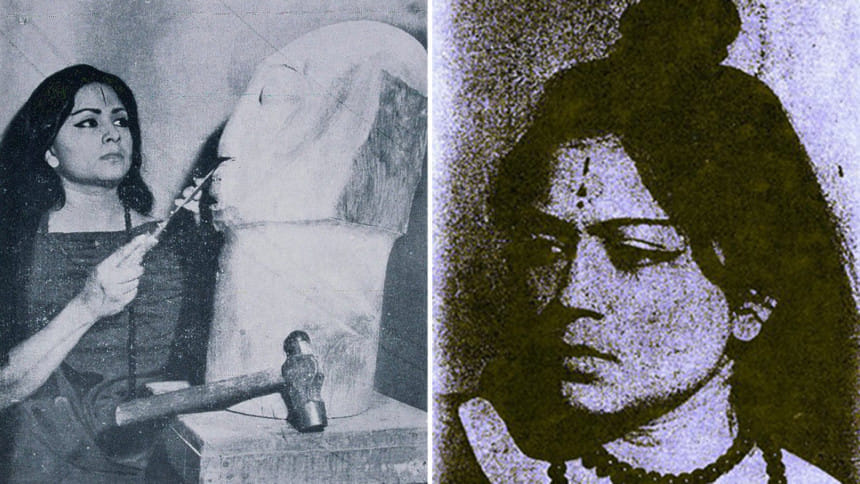

She is remembered mostly as the woman who dressed as Baishnabi wearing rudraksh garland and the confident figure who went about boldly in a reactionary society of the 50’s.

But little do people know that Novera longed to return home and owned Bangladesh in her heart.

"She was the forerunner of modern women emancipation – expressing liberty of women at a time when no one dared," Ekushey Padak winning litterateur Hasnat Abdul Hye says on the artist on a one-to-one talk with The Daily Star.

Novera introduced modern sculpture in Bangladesh at a time when the erstwhile East Pakistan ruled fine arts institute, now Faculty of Fine Arts in Dhaka University, did not have a sculpture unit.

"The most striking thing about Novera was her lifestyle. She dressed beautifully – like a Baishnabi – wearing Rudrashkh garland and a small bun on top of her head – in one word that was characteristic at a time when society bound women to their homes," Hye said.

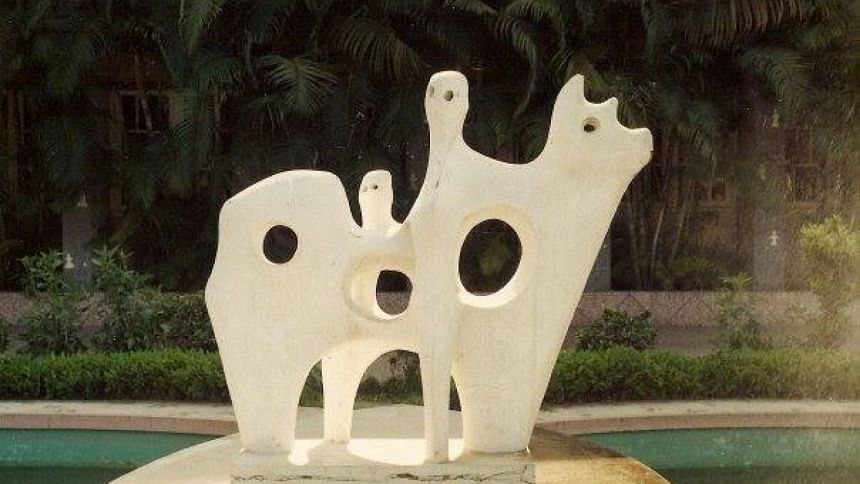

"Her works, in the primary stage, was mostly influenced by Henry Moore. But later, she managed to sprout her individualism and avert from any influence."

After her exhibition, Novera had left the country after 1960 and has been in isolation since – mostly forgotten for over 30 years before resurfacing in writings and discussions after in the 90’s.

'BANGLADESH IN HER HEART'

"The first time I met Novera, she was dressed in a black saree and welcomed me inside in Bangla," Anna Islam, art critic, writer and the wife of artist Shahabuddin, told The Daily Star.

That was a day Anna Islam had dug out Novera after years of frantic efforts in Paris. Since then the two remained in touch for 18 years until Novera's death.

"Novera was never in hiding. She had to leave Bangladesh for family and social problems, but it was her earnest desire to return home."

"Last October (2014), she was reminiscing her days in Bangladesh. She was telling me how she wished she could take her wheelchair beside the Shaheed Minar and draw."

Novera suffered a stroke in 2010 and she was in a wheelchair since. But that did not stop her from pursuing her passion. She practiced regularly and her latest exhibition was in Paris in 2014 titled Retrospective in a boutique shop she owned with her husband.

"Bangladesh was in her heart. And everything she did proved it. Some of her paintings were named in Bangla. And she had cats, lots of them. They were all named in Bangla. As I remember their names were like gunda (thug), bador (monkey) and what not!"

"She always wore saree and loved Bengali food - biriyani, rasogolla, and others. I used to take them to her house and she would love it."

Before Bangladesh's liberation, Novera lost her uterus to cancer and lived by her husband Gregoire de Brouhns until the last minute. The two were married since 1984 though they knew each other from long ago.

Seriously ill since January this year, Novera was often shifted to hospitals before the last few months where doctors had set up necessary facility in her home. In comma for the last two days, the artist died in her sleep around 4:00am Paris time on Tuesday.

'LOST IN THE IGNORANCE OF A PATRIARCHAL SOCIETY'

“Even when we were students, we knew so little about her,” reminiscences Lala Rukh Selim, an artist, sculptor and the incumbent chairman of Dhaka University Faculty of Fine Arts’ sculpture department.

“But as Shilpacharya Jainul Abedin wrote in Novera’s 1960 exhibition: What Novera is doing now will take us a long time to understand – she is that kind of an artist.”

Her flamboyant lifestyle after she came to the country in 1956 with learning from the West earned her discredit too. Lala Rukh reckons those were mostly stemmed from the slanted view imprinted by the patriarchal society of Bangladesh.

“There has been very little discussion on her works. We should understand her as the unique artist she was during her time.”

Now, though sculpture students are more familiarised with Novera Ahmed, it is not enough, she says. “We need to shed more light on her. She demands more attention.”

As to why such a remarkable artist has been in isolation for over the years, Hasnat Hye had all blames on the society and artists. “It’s all our fault. We could not uphold a calibre artist like her.”

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments