Ancient tamarind tree, a community's pride

Long ago in Chapainawabganj, potentially during the reign of the Mughal emperor Jahangir, whether by gravity's force or human hand a humble tamarind seed met the soil. Half a millennium later, that majestic tree which sprouted and grew in Surola village in Nachole upazila still bears fruit. It is likely the country's oldest tamarind tree.

“The tree hasn't changed in generations,” says a local elderly woman, Kusum Begum. “My mother saw it in the same condition.”

“From April every year, hundreds of cranes arrive,” notes another local, Soshthi Chandra Pramanik, 65. “They build nests in the tamarind tree and raise chicks there. Only when the chicks are sufficiently mature do the parent cranes fly away. Parrots and owls also find safety in the tree. Nobody in this area hunts birds.”

Kalpani Rani who also lives nearby is in the habit of sweeping under the tree every day to keep the area tidy. She collects its leaves. “The tree and the birds are like my children,” she says, though she's not the only one in the locality to tend the tree.

Five centuries is a long journey. The Mughal Empire would reach its zenith and fall; the British would arrive; the years of East Pakistan would end. Since 1971 the tamarind tree has been gracing the roadside fifteen kilometres from the district town in a liberated Bangladesh, symbolically, on public land.

Five centuries is a long journey, but the story of the tamarind is much longer. Believed to be a species endemic to tropical Africa, the tamarind was first introduced to South Asia many thousands of years ago. Its tasty fruit and useful wood encouraged people to let it flourish, so much so that the tamarind is often considered a native species. Indeed the English word stems from the Arabic “tamar Hind”, meaning “Indian date”.

It's not only political upheaval the tree has witnessed. It has weathered each season through drought and rain. Forty-five years ago the tree's largest boughs succumbed to a storm, but the tree lives.

Villagers are proud of their ancient tree. They say there was once the farmhouse of a landlord in the village, and it may have been the zamindar Kunja Mohon Mitra who had a Kali temple positioned under the tree's branches. Hindus, including indigenous people, still worship Kali there; other visitors in significant numbers arrive from afar to see the tree.

Perhaps it's an attribute of fondness that it tends to extend dates. Locals will readily report that the tree is six or seven hundred years old. But according to department of agricultural extension officials, carbon dating has suggested the tree is five hundred years old. “Regardless of its precise age, this tree is ancient,” the officials note. “It has social, biological, ecological and economic importance.”

The deputy director of the district's horticulture centre Dr Saifur Rahman says that old trees transpire huge amounts of water through their leaves, which contributes to rainfall. It also provides oxygen, improves air quality and preserves soil, as well as supporting wildlife.

Shahidul Huda Alok, a committee member of the local environment group Save the Nature, notes the tree still provides fruit as well, and, as the heart of the area's ecosystem, the forest department should take initiative to protect it.

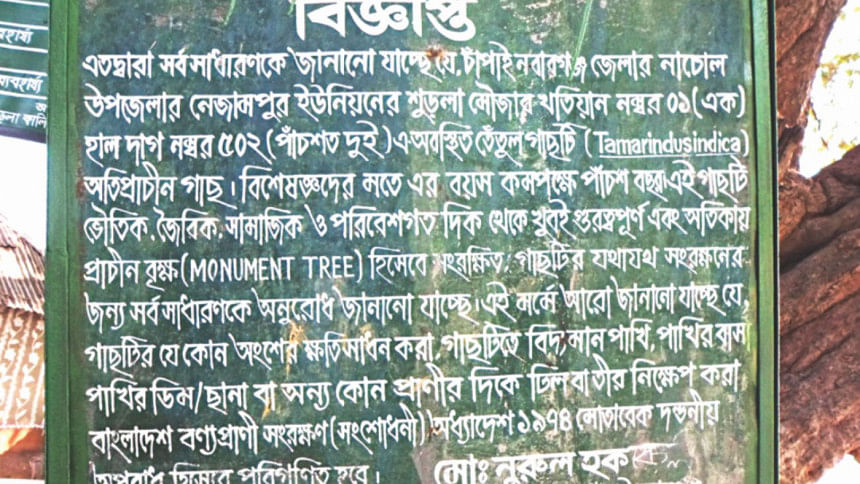

Indeed, fifteen years ago the then-deputy commissioner for Chapainawabganj, Nurul Haque, planned to establish an eco-park around the tree, with road construction, electrification and forestation to follow. So far, only a signboard has been placed there.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments