Jessore's signature date juice gets scarce

As the Bangla saying goes, “Khejurer rosh, Jessorer josh,” roughly meaning, “Wild date palm syrup is the pride of Jessore.”

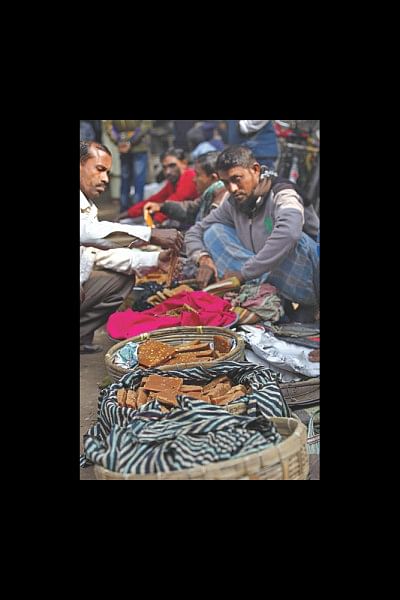

Alternately known as the wild, sugar or silver date palm, phoenix sylvestris has been cultivated in its native subcontinent for centuries. In Bangladesh its sap is tapped to be consumed fresh, or processed into either syrup or the jaggery known as “gur”. Nowhere is the wild date palm more synonymous with local identity than in Jessore, but with the number of trees in decline, how long the age-old saying will hold true is uncertain.

The juice with its earthy, sweet botanic taste, is widely loved. “The taste of wild date palm syrup of a winter's morning is heavenly,” says Yasmin Akhtar Jesmin of Jessore's Bejpara. “Winter is worthless without palm syrup and gur cakes.”

Unfortunately, for future generations the sweet delights of the wild date palm might not be such a quintessential marker of winter. Date trees are declining in numbers and few people are interested in taking up date syrup harvesting as a profession now.

“In the first decade of this century wild date palm numbers fell by about 30pc nationwide,” says Rofiqul Alam, who worked as director of a Bangladesh Sugarcane Research Institute project covering Palmyra, nipa and wild date palms. He notes the palms grow in about 30 districts where conditions are favourable, including throughout greater Jessore.

While Alam's estimate is based on experience, the exact number of wild date palms in Bangladesh is unknown. One survey from 2010 records that up to 15,000 hectares of the country are covered by either wild date or Palmyra palms.

In Jessore, the Department of Agriculture Extension (the DAE) tallied the number of trees at around 7 lakhs in 2008, falling to 5.41 lakhs by 2013, before rising again to 6.75 lakhs in 2015, a rise they attribute to their own initiatives.

Nonetheless it is commonly observed by Jessore locals that the number of mature palms has decreased, despite strong demand for the tree's syrup.

The deputy director of Jessore DAE Nittyaranjan Biswas believes a major reason for the decline is because there are fewer professionals, known as a “gachhi”, available nowadays to cut the tree trunks and extract the sap.

“One of my employees,” Biswas says, “sold four of his wild date palms to a brick kiln because he couldn't find any skilled gachhi to extract the sap. Many people are leaving the profession because the season only lasts for the winter months.” Demand for firewood from brick kiln is another factor influencing the decline.

Another DAE official in Jessore, Rafiqul, echoed such sentiments. “Due to the short season, few take on sap extraction as a job,” he says, “despite the good prices for palmjuice and gur.”

Abdul Gani Gazi, 70, of Pantapara village in Jessore's Khajura area worked as a gachhi since he was 16, but even he has sold most of his trees. “I used to have over 100 palms but now there are only 17. Many people are selling their trees because they can't find anyone prepare the trees for the sap collection.”

“None of my 7 children were interested in this work,” he continues, “They think differently and find the work of a gachhi a painstaking work, even though the income is okay.”

“To save the date palm tradition we need to apply modern extraction techniques,” says Alam. “Palm syrup and jaggery are valuable products because of their nutritional content. They are better than sugar.”

“Besides,” he continues, “a wild date palm will produce sap for up to 50 years, with first harvest available after 7 years. It's a good investment that doesn't require much care.”

In efforts to save the tradition, Mamunur Rashid, secretary of art school Charupith Jessore, recently organised a date palm festival in Jessore to generate enthusiasm. He believes government initiatives can also help to save the date palm, with its significant economic, cultural and ecological values.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments