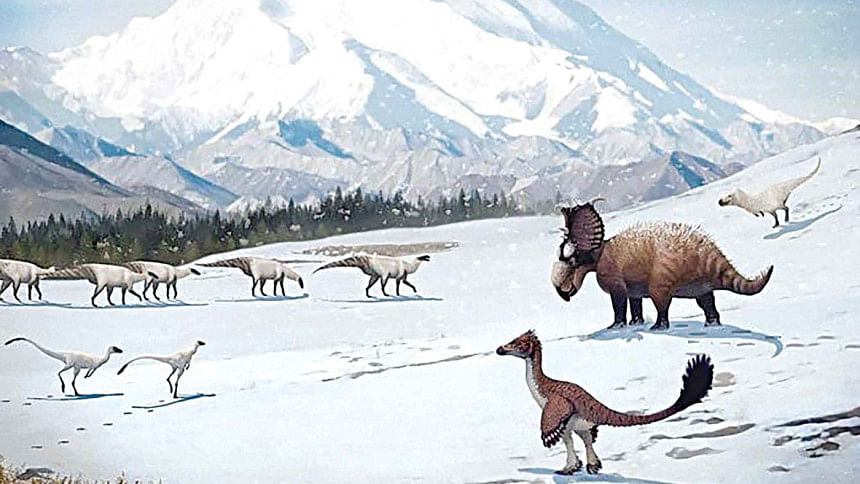

Dinosaurs thrived in ancient Arctic

Dinosaur species large and small made the Arctic their year-round home and probably developed wintering strategies like hibernation or growing insulating feathers, according to a new study.

The paper, published Thursday in the journal Current Biology, is the result of more than a decade's worth of painstaking fossil excavations, and puts to rest the notion that the ancient reptiles lived only in hotter climes.

"A couple of these new sites we found in the last few years turned up something unexpected, and that is they're producing baby bones and teeth," lead author Patrick Druckenmiller of the University of Alaska Museum of the North told AFP.

"That's amazing because it demonstrates that these dinosaurs weren't just living in the Arctic, they were actually able to reproduce in the Arctic."

Researchers first discovered dinosaur remains at the frigid polar latitudes in the 1950s, regions once thought to be too hostile for reptilian life.

This led to two competing hypotheses: Either the dinosaurs were permanent polar residents, or they migrated to the Arctic and Antarctic to take advantage of seasonally abundant warm resources, and possibly to reproduce.

The new study is the first to show unequivocal evidence that at least seven dinosaur species were capable of nesting at extremely high latitudes -- in this case the Upper Cretaceous Prince Creek Formation which lies at 80-85 degrees North.

The species uncovered include duck-billed dinosaurs called hadrosaurs, horned dinosaurs such as ceratopsians, and carnivores like tyrannosaurus.

The team are confident the tiny teeth and bones they found, some of which are only a few millimeters in diameter, belong to dinosaurs that were either newly hatched or died just prior to hatching, because of their distinct markings.

"They have a very specific and peculiar kind of surface texture -- it's highly vascularized and the bones are growing quickly, they have a lot of blood vessels flowing into them," explained Druckenmiller.

Unlike some mammals such as caribou that give birth to young that can walk long distances almost immediately, even the largest of dinosaurs had tiny hatchlings that would have been incapable of making migratory treks of thousands of miles (kilometers).

What's more, given what is known about how some species incubated their eggs well into the summer, the dinosaur young would not have had time to mature and be ready for a long journey before winter arrived, the team argues.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments