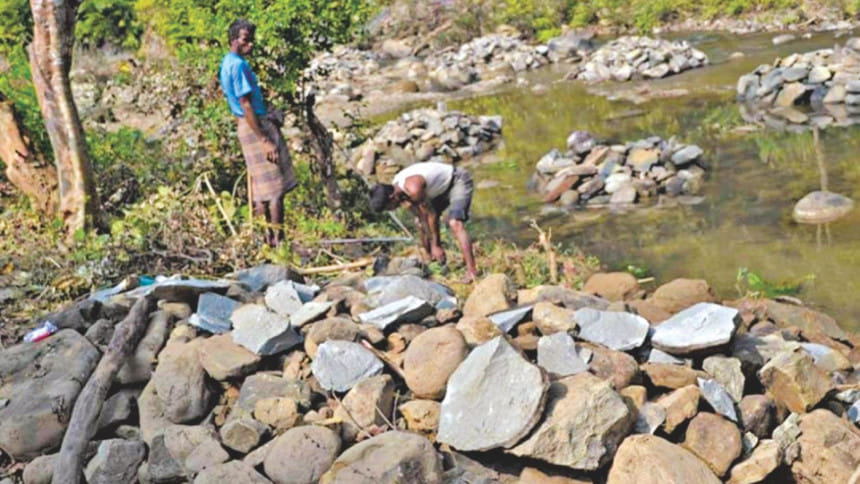

Streambed in peril for stone extraction

The villagers of U Bang Koi Marma Para in Bandarban are struggling to find water. It's not the result of a calamitous drought but an entirely manmade problem. Traditionally, water from local streams collects in a small type of pool locally known as a 'jiri', but as the rocks trapping the water are poached, the jiri is gone leaving only the streambed, which runs dry. Across Bandarban district the illegal extraction of river stones is rampant.

“We're facing environmental disaster,” says the local area's chief, Mong Nyo U Marma. “Most of the rocks have been taken from our water bodies. Water security for the people is lost. Stone extraction in the hill districts must be stopped immediately.”

Chaw Thoai U Marma, a local from Naidari Para which is also affected by stone poaching, agrees. “We used to get water from jiris but now water in the dry season is scarce. Stone lifting in our area continues unabated.”

Many local indigenous communities depend upon jiris for water. Moreover, stone extraction from hills, waterfalls and canals creates landslide risk and upsets the ecological balance, with wildlife also suffering in the landscape of fast-dying streams.

Yet the rock extraction continues, under the very nose of the district administration, forest and security officials. Indeed the addition of the extra sediment once held in place by rocks is also contributing to the siltation problem in the Sangu River.

Rock lifters told The Daily Star that up to 1,800 maunds of hill-rocks are collected daily in Bandarban, in defiance of the law and particularly during the dry season when the rocks are most accessible. Primary buyers of these supplies include local municipalities and various government bodies including the local government and engineering department, the public works department, the Chittagong Hill Tracts development board and the department of roads and highways.

Sources say contractors pay hefty bribes to high officials within these departments to overlook the use of illegal construction materials in various construction projects.

“I managed the district administration in order to extract hill rocks,” says Shankor Das, one rock trader. “Many people extract hill rock because it's a profitable activity.” Along with fellow trader Md Milon he says he is unaware of any adverse effect from rock extraction.

Divisional forest officer Kazi Kamal notes that many rock extractors in the district are ruling party members. He also says the forest department could not take immediate action to stop them due to manpower limitations.

“I have directed all upazila nirbahi officers to take necessary action to prevent anybody from collecting hill rocks illegally,” says Deputy Commissioner Dilip Kumar Banik. “A special inspection team has been formed in this regard.”

Despite the deputy commissioner's assurances the on-the-ground situation is rather different. In numerous remote locations across Lama, Ruma and Thanchi upazilas, from the Ruma and Sona canals to Naikkhong, Konadi and Hailmara Jiris, stone lifting has damaged water resources. Many indigenous communities are increasingly facing the threat of eviction due to this environmental catastrophe.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments