Fazle Hasan Abed’s Bangladesh

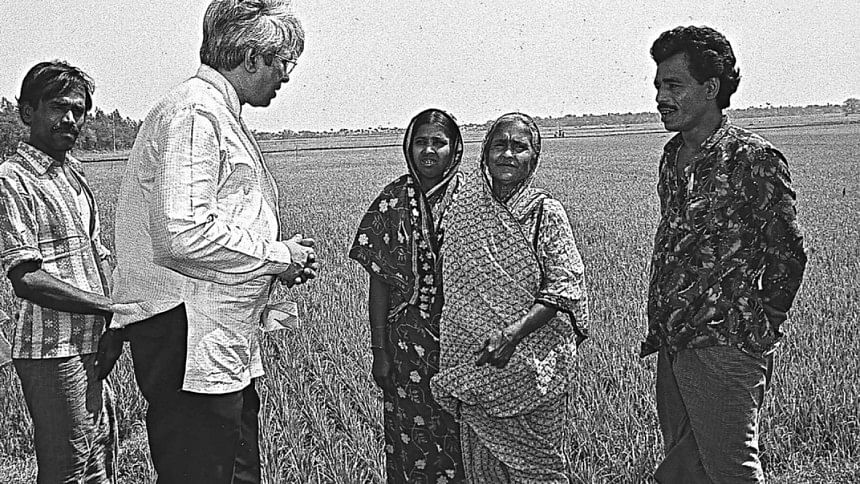

He was born on April 27, 1936 in a famous zamindar family of Baniachang, Sylhet. He passed away on December 20, 2019. He left behind his work and his organisation BRAC. He is still alive in the hearts of people. I am talking about none other than Fazle Hasan Abed. Thanks to a book writing opportunity, I had the good fortune of getting close to him for a few consecutive years. Together, we visited many places of Bangladesh. I saw and I learned about various activities of BRAC. I also came to know about different aspects of his personality.

The topic of discussion was the politics in Bangladesh. In that context, the issues of Shalla and Suranjit Sengupta were brought forward. The first activities of BRAC in the independent Bangladesh started in Suranjit Sen Gupta's area Shalla of Sunamganj. He was delighted to know that BRAC would conduct reconstruction work in his area. The car was moving along the way towards North Bengal. The year was 2004, and we were talking about the events of 1972. I asked, how do you remember the time? In his usual manner, he looked around and smiled at me. After remaining silent for a few seconds, he said certain things, which I may not be able to quote word by word. However, the point he mainly made is that none of the events of that period can be termed "memories". Those days are still just around the corner, or he is still living and working through them.

I can still see those scenes in front of my eyes like a picture.

33-34 years is not a short period of time. Today's Bangladesh is much different from that period's Bangladesh. The car we were riding, or the road through which we were travelling was quite unimaginable in the year 1972.

He smiled again, and started talking, "I imagined a happier and more prosperous Bangladesh; not the one we have now.' I used to visit Shalla in 1972 by travelling through difficult roads. I didn't feel any pain back then, and I still do not find it painful to remember those days." The success in Shalla smoothened the way for the future endeavours of BRAC. From the very first day, the way he conducted all the work is such a tale that, no matter how many times I hear it, it never fails to surprise me. He went to Shalla and handpicked educated young people who did not have work. He deployed them to collect data on damages. With the help of some teachers from the statistics and economics departments of Dhaka University, he analysed the collected data and determined the actual magnitude of the damages, and also the way forward. He brought enough tin from Japan to build 14 thousand houses. He brought 6 lakh bamboos a huge amount of wood from Assam by floating the materials through Kushiara river. He built homes for people without any kind of irregularity or corruption. He also provided healthcare. BRAC managed to change the face of the war-torn Shalla within a few months,

In Fazle Hasan Abed's own words, 'I went to London in 1972. There, I found out that the Oxfam officials are very happy with our work. BRAC was one of the best performing projects among the 700 projects that they were running across the globe. For that reason, getting money for our work became much easier.

On April 24, Dr Muhammad Yunus, the only Nobel laureate in Bangladesh, spoke about the work of Fazle Hassan Abed. He said, 'All the people of Bangladesh have been touched by the work of Fazle Hasan Abed, one way or other. The span of Abed's activities was so vast that no one could be left out of its reach. Education, health, poverty alleviation, handicrafts—everywhere Abed has left his mark. Fazle Hasan has totally changed our traditional concepts of an NGO. He did things that no one could do before. No disaster could hold him back, he stayed in the frontline and became successful.

I have written in the past about the distinct mark he has left behind in all kinds of work. From those writings, we can know about his extraordinary and memorable contributions to different fields like edible saline, micro-credit, education, vaccination and many more. I want to say a few words in this context; mainly focusing on two fields where he has significant contribution.

One is Jamdani and the other is Nakshikatha.

Both of these are highly prestigious industries of Bangladesh. However, both the industries went on the verge of extinction. BRAC conducted a survey during the period 1978-79, and found out that 700 families in Demra area used to produce Jamdani. There are many legends regarding the Jamdani crafting of this area. Apparently, the Jamdani worn by the daughters of the Mughal emperors was so finely made that it could be inserted inside a ring. However, the families were leaving the craft and switching to other professions. BRAC attempted to revive the tradition, but soon found out that the Jamdanis that were produced within the last 200 years were not available. The tradition of Bangladesh was not available to us, instead, it was preserved in the famous museums of the world.

Fazle Hasan Abed said, 'The Kalika museum of Ahmedabad in India, The Ashutosh museum in Kolkata, Chicago museum in America, and a number of other museums preserved these Jamdanis. I took photographs of those Jamdanis from the museums, and made slides out of them'.

Another glorious tradition, Nakshikatha, was also going through the risk of obliviating. The motif and the stitches of the Nakshikathas made in our country within the last 300 years nearly got lost. Just like the Jamdani, the Nakshikathas were also preserved in some of the world's most famous museums. Photographs were taken from many museums, including the Folk museum of Boston and Chicago museum. Artists were commissioned to draw those extraordinary Nakshikathas on paper.

Fazle Hasan Abed said. 'I gave the paper designs to the women. They reproduced them on the Kathas through needle stitches. This way, we revived the Nakshikatha and the Jamdani industry. Using the motif used in the Jamdanis produced within the last 200 years, we made about 300 Jamdanis. We organised a Jamdani exhibition in Shilpakala Academy in the year 1981. At that time, I met the then president Ziaur Rahman and informed him that I want Madam Zia to inaugurate the exhibition. However, he did not agree. Alternatively, he suggested engaging foreign minister Shamsul Hoque for the inauguration.'

Fazle Hasan Abed has also contributed towards the Jamdani and Nakshikathas of today.

Fazle Hasan Abed used to mention one point every now and then; Bangladesh has not yet reached the objectives that were aspired during the country's independence. Still many are left impoverished. Independent Bangladesh could not align itself with a political system similar to the political thoughts of Sheikh Mujib during our liberation struggle or Tajuddin Ahmad's strong and prudent political moves during the days of war.

A specific example used to pop up in our discussions every now and then. When BRAC was working in Shalla, we came to know that the Roumari area of Rangpur is going through a severe food crisis. After travelling through many treacherous roads, BRAC reached Roumari and started working there. However, the local politicians started embezzling the aid that was meant for the famine and hunger struck poor people. Despite a lot of efforts, the stealing could not be stopped, and BRAC was forced to withdraw from Roumari. On this aspect, Fazle Hasan Abed said, 'Food supplies meant for the hungry people were getting embezzled. We tried reasoning with the local political leaders, repeatedly. But they did not pay heed. And thus, we decided to withdraw all our efforts from Roumari, with the logic that if we continue in this manner, people may assume that we are also involved in the corruption. If people's thought moves in to that line, soon, the news will also reach the ears of the donors. That will tarnish our image, and our future will be jeopardized. We left behind everything else and we were solely working for the welfare of the people. Good reputation was our principal strength.'

Soon it became evident that the political system in independent Bangladesh was not going in the right track. The leaders of Awami League started thinking that they have liberated the country by engaging in a war, and now they deserve some rewards. Many of the Awami League leaders were Fazle Hasan Abed's friends. He tried to explain the issue to them. However, none of them paid much attention to what he said. Soon, an enlightened personality like Tajuddin Ahmad was sidelined.

Fazle Hasan Abed said, 'If he wanted, Nelson Mandela could have held on to power for another 10 years. He led the movement, tasted victory, and ascended to power. He paved the path for others by setting an example of just leadership with the hope that his successors would farther smoothen the path and move forward gracefully. He could only do this because he was a broad minded individual. Gandhi also did the same. He did not assume power himself. He stayed on a position of respect and gave guidelines to the nation. The same could have happened in our country. And if that happened, the objectives of liberating Bangladesh could be fulfilled.'

The issues of the freedom fight and Tajuddin Ahmad becomes a recurring theme in any political discussions we had. In September, Fazle Hasan Abed met the war-time prime minister Tajuddin Ahmad in Kolkata. There was a specific objective behind this meetup. At that time, Fazle Hasan was in London, and working in support of Bangladesh's freedom fight. He met a group of people in London, who worked as mercenaries during the Vietnam war. Two of them hailed from England and Australia, respectively. He arranged for them to take a fishing trawler from Gujrat coast, and to take it near the Karachi sea port to cause an explosion in a ship. The incident was supposed to be depicted as a doing of the members of the freedom force. For this, the mercenaries asked to be paid 13 thousand 800 pounds. Fazle Hasan Abed and Vikarul Islam Chowdhury managed the required amount, and travelled to Kolkata to inform the prime minister Tajuddin Ahmad. They thought it would not be prudent to cause such a massive incident without duly informing the Prime Minister.

Fazle Hasan Abed said, 'Me and Vikarul Islam Chowdhury went to his office in Kolkata's theater road. We entered his room at 7 PM. He was sitting on a chair, wearing lungi and Panjabi. We informed him about our plan. He listened to it attentively.' Then Tajuddin Ahmad said, 'This kind of operation may or may not succeed. Thus, it will not be wise to spend so much money in this endeavor. We are going through severe financial crisis. We are totally dependent on the Indian government. They are giving us many things, but then again, they are also holding back from giving a lot more, too. If we get the money you have collected, we can fight our own war. We will not require the service of mercenaries.' Yu

'Tajuddin Ahmad seemed to be a humble, amiable and idealistic political leader. In the absence of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the hero of the liberation war, he was acting as the main organizer of the liberation war for all of us. '

Eventually, he rejected the plan of causing an explosion. At Kolkata, Vikarul Islam Chowdhury met student leader Rashed Khan Menon. Menon informed that the freedom fighters will require six thousand sweaters during the upcoming winter season. Fazle Hasan Abed met Ziaur Rahman. He came in to acquaintance with Major Zia during his stay at Chittagong, where he was working as an employee of Shell. Ziaur Rahman informed certain details of the war situation. He mentioned that they did not have any binoculars. 'Binoculars help a lot during a war', said Zia.

Fazle Hasan Abed returned to London. Vikarul Islam Chowdhury stayed back in Kolkata. As per the requirements of Rashed Khan Menon and Ziaur Rahman, both binoculars and sweaters were arranged.

Fazle Hasan Abed continued, 'I came back to London and started collecting funds. I thought, the war will last long. We wanted to create a food storage silo along the border area. From there, food would be sent to the free areas of Bangladesh. Not only non-resident Bengalis, a lot of foreign nationals also donated money for the liberation movement with open arms. A British woman sent one pound, and wrote that, I will not eat eggs for the next two months. I am giving that money to you. I never got a chance to meet that woman.'

Since the birth and dawn of independent Bangladesh, Fazle Hasan Abed and his hand-built organization BRAC has been deeply entwined with her overall progression, in all areas and aspects.

Golam Mortoza: Author of the book 'Fazle Hasan Abed O BRAC'.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments