Literature and the City

Urban spaces have deeply contradictory existences in our imagination. We love cities and the goodies they offer; we also hate them and often dream of escaping the ruthless, mechanical life they impose on us. Cities embody the human desire to master and manipulate nature more powerfully than does any other built environment. Cities are anthropocentric, for they grow by encroaching on the natural environment, eliminating in the process species and vegetations that are considered extraneous and threatening to human needs. Cities are also utopias; human desire—good or bad—gets expressed in them in various forms of political, economic and cultural activities. In the twenty-first century, the city has attained immense significance not simply because of its complex and contradictory existence but also because of new realities that gesture towards the city's preponderance in this stage of human civilization. For the first time in human history, more people now live in the cities than do in the non-urban areas.

As a student of literature, I have always found writers' representations of the city deeply fascinating. But far too many literary works have thematized cities as threatening and corrupting entities. In William Blake's poems one finds a London that is not only sick but also predatory and corrupting—a place in which child labor, prostitution and political oppression echo in the daily existences of people. Ninteenth century literature is replete with images of carceral cities ready to devour poor working class people. It is no coincidence that a majority of Charles Dickens's novels chronicle the dogged life of the urban underclass, especially orphans.

Although not a fictional work, Friedrich Engels's The Condition of the Working Class in England offers profound observations on not only the condition of the British working class who were forced to embrace the unhealthy, traumatic life of the city, but also the process that brought them into the cities in the first place. Written during Engels's visit to Manchester in 1942, this book carefully documents how modern industrial cities like Manchester forced upon its working class inhabitants an inhuman life. Engels notices that the glitzy appearance of cities such as London and Manchester concealed the gruesome reality of workers' exploitation, premature deaths, dingy and unhealthy cityscapes, orphaned children, destitute women and Irish migration. The main streets of big cities paraded to him shiny, well-lighted shops selling expensive commodities. The inner parts that remained hidden behind these stores and wealthy people's mansions, however, were dingy and slum-like, infested by disease and death. One of Engels's most important observations in this book is that like capital, population also becomes centralized. After all, the centralization of capital draws people in from different parts of the country. Modern cities are thus spaces created by capital; here bodies are advanced for commodity production just as capital is also advanced.

The deep anxiety about the city persisted until the mid-twentieth century when England, as well as much of Western Europe, was able to externalize the problem of primitive accumulation and export them over to the Third World, most of which suffered the consequence of colonialism. The city as a location of positive experience began to emerge, it seems, at the beginning of the twentieth century. Although the French poet Charles Baudelaire anticipates the urban consciousness of many of the modernist poets and writers who succeeded him, in the great poet's work one notices not only the pleasures of the city but also its vices. Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness carries on with a similar complex representation of urbanity. In the first scene of the novel, when Marlow reflects on river Thames and the city of London, he characterizes the latter as a place of both light and darkness. London, in Marlow's narration, emerges as a busy, opulent city threatening its environs with its "ominous" presence. James Joyce's Dublin, not dissimilarly, is simultaneously a space of freedom and a space of restriction and struggle. To read Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as A Youngman and Ulysses is to understand how the Dublin at the turn of the century was an acutely political space gravitaitn between pro-colonialist and anti-colonialist impulses.

European modernist literature thus both fetishizes and demonizes the city. While cities remain the locus of modernist romance, one must not forget that modernist literature also thematizes some of the most painful experiences of urban life: poverty, alienation, death, war, policing, betrayal, exploitation and repression

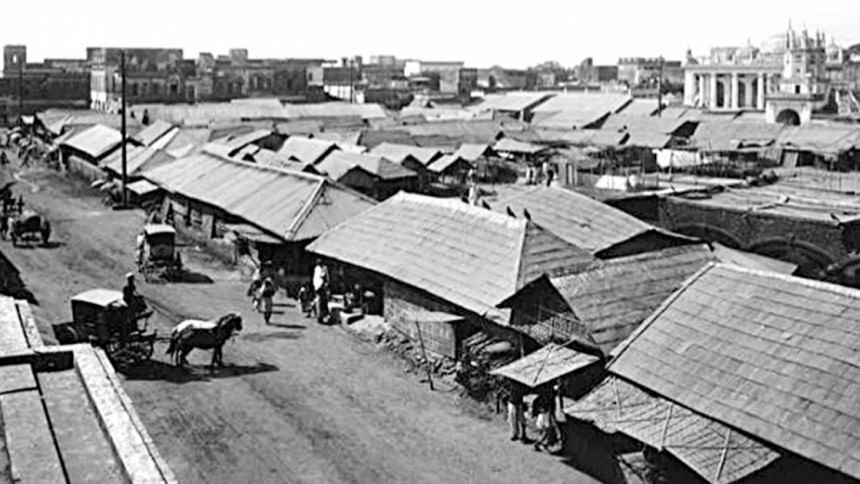

The celebration of urban life also abounds in Bangla literature, but here too one finds critical reprsentation of urbanism. Two of my favorite writers—Akhtaruzzaman Elias and Shahidul Zahir—have immortalized old Dhaka by using it as the setting of some of their most remarkable works. Elias's powerful short story "Utsob" (The Carnival) explores the nexus between sexual desire and affluence by presenting parallels between Dhanmondi—the abode then of the nouveau riche—and Old Dhaka—where the story's protagonist lived among workers, decaying aristocrats, vagabonds, and animals. Anwar, the protagonist of the story is a university educated petty clerk struggling both materially and sexually. His friends keep flaunting their wealth and their success present him with the same jealousy and crisis as do their slim figured smart wives. This remarkable story not only captures the tension and unequal exchange between the two Dhakas, it also explores the grotesqueness of human desire by collapsing the boundary between human and animal desire.

Like Elias's, Shahidul Zahir's fictions also use old Dhaka as their preferred setting. What distinguished Zahir from Elias is the former's strategic use of collective narrative voice and defilement of formal rules of punctuation. Shahidul Zahir's most celebrated works such as "Amader Kutir Shilper Itihash" and Abu Ibrahimer Mrittu (Abu Ibrahim's Death) employ collective narrators to pluralize and collectivize experience.

Elias and Zahir have creatively explored the poverty, the corruption, the struggle, and the sickness of Dhaka's life; they have also depicted, with much insight, the glory and triumph of this remarkable city which has stubbornly resisted oppressions of various kinds, perpetrated so often by the ruling nationalist bourgeoisie and military dictators. Both have captured in their stories the trauma of our liberation war and the genocide carried out by the Pakistani military and their local collaborators in 1971. More importantly, Elias and Zahir have also narrated how Dhaka has ended up becoming an oppressive sprawl whose concentration of wealth has and facilities has been achieved by denying other parts of the country the same right to life and services.

I grew up in a colony located in the Motijheel area at the juncture between old Dhaka and new Dhaka. Growing up in the 1980s and the 1990s when Dhaka was still livable and not as densely populated as it is now, I have seen the city deteriorating into a massive slum, full of glitzy malls and dingy apartments. The mango and coconut trees we grew up with are gone now and the sheuli that brought so much joy in our lives every morning through fragrance and color has become almost extinct. The entire bird population is almost gone. Other animals, including monkeys, have either perished or found shelter in other parts of the country. The entire city now looks and smells like a massive dustbin, with no delicate scent to save us from the assault on our noses. Neoliberalization of the economy, capitalist greed, political corruption and systematic erosion of life in the rural areas has taken my city away from me. If I now look into the literary representations of the cities of recent decades, it is because inside me lingers a deep sense of loss—a trauma I bear because my city has been taken away from me. In order to survive in it we—you and I—must reclaim it and take it away from where it is now—not to its past since that was another realm but to a better and more livable, lovable city.

The author is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments