Migrant workers are just not numbers...

About a year and a half ago, Shahidul Alam told me about how he wanted to do a project on migrant workers going from Bangladesh to Malaysia. At the time, migration had just become a hot topic in the news, both with the escalation of the Syrian refugee crisis and also with the discovery of migrant camps and mass graves of migrant workers near the Malaysian-Thai border. The "Asian Migrant Crisis" as it was then termed eventually vanished from the headlines and banished to the back of our heads to gather dust as something that happened in a far away land. Since then, Shahidul Alam has worked tirelessly and efficiently in putting together his book on Bangladeshi migrant workers in Malaysia, titled The Best Years of My Life – a collection of portraits and stories of workers, employers, government officials, activists and manpower exporters that he encountered during his research, covering nearly every step of the labour supply ladder. He delves into successes and the hardships faced by poor Bangladeshi migrants as they chase opportunity and a better future in tepid and cruel conditions in Malaysia, as well as showing the benefits to a country like Malaysia that has been gained from the influx of Bangladeshi labour. He analyses various structural and institutional problems and hurdles that exist for these migrants and how social mobility acts as such a determined driving force for these people to sacrifice, to display unimaginable selflessness, for the sake of their families that they were forced to leave behind.

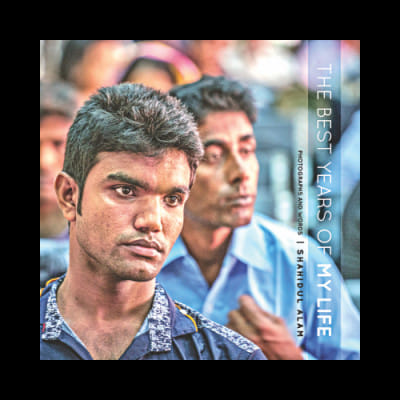

As the author is a renowned photographer, it was important to see the photos in Alam's book, as much as reading the stories. What's most striking though is possibly the lack of striking in the pictures. These are not heavily stylized, dramatic black and white or decked out with light flares, but the photos themselves carry an air of, for lack of a better word, matter-of-fact-ness. And that's what hits hardest. The implicit acceptance that hundreds and thousands (millions worldwide) of poor Bangladeshis are routinely swindled by dalals and sent to Malaysia where they live in decrepit conditions, work like modern day slaves, are abused by their employers and treated without the smallest modicum of respect, and we, especially we, of the privileged classes, accept that as a fact of life for these people. Alam's pictures show regular people, and what appear to be regular lives, and yet, that is what is so troublesome about the apathy toward this class of people. The words on the pages routinely mention multiple horrible things happening to migrant workers on their journeys chasing economic progress – passports taken, arrests, having to pay bribes, being in debt, beaten and abandoned – but the pictures of Abul Hossain, Masud Rana and Nazrul Islam do not exhibit this. This, I feel, is an important show of respect in the creative direction of Alam. To simply show them as people, is already a challenging affront to the comfort of dismissing migrants as numbers and far-away occurrences.

Two photographs in particular stand out to showcase the scale of the issue. The first is a panoramic shot of the line at the Bangladesh High Commission of migrant workers waiting for new passports. In the interview with the High Commissioner, he says the High Commission receives anywhere between 2000 and 3000 (sometimes exceeding that number), whereas the High Commission is only equipped to process about 300 people a day. It is also revealed that the middlemen are really the ones the workers have contact with, rather than the embassy. This is an important example of the administration's failure to take care of its citizens working abroad, something that also translates to our incapability create safer, legal avenues of sending labour abroad. This vacuum is then filled by the dalals, and already vulnerable human beings are further forced to pay to seek employment (rather than the other way around).

The second photograph is a haunting wide angle shot of the grave markers near the Malaysia-Thailand border. Taken in bright daylight, with blue skies and fluffy clouds in the background, it makes it all the more painful to look at. In straight lines, packed together in uniform markers, the grave sites are disturbing and quite hard to look away from. It is a stark reminder of the risks that these people take, literally putting their lives on the line, to pursue a shot at a better life – sometimes not even for themselves.

The idea for Alam's book, The Best Years of my Life, is simple, and incredibly necessary – he endeavours to attach a human face to what is a human problem, yet so often lost in the effect of quantification and statistics. This book is so very timely, purely because it screams out loud that these are real people, not just data, not just numbers. The risks they take, the challenges they face, the hopes they harbour and the sacrifices they make are distant narratives to us who are privileged enough not to have had to lead the lives migrant workers lead. Alam tries to remind us that these narratives are not so distant, and through the use of his portraits, pushes a greater understanding and more importantly, a greater empathy to this extraordinary human struggle.

The reviewer is an occasional contributor to this page.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments