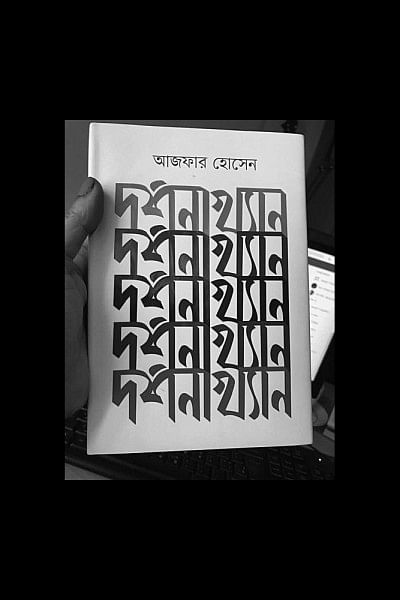

Azfar Hussain’s Dorshonakkhyan: Materialist Philosophy

In Hegelian philosophy, the dialectical relation between appearance and reality is an important relationship. Marx brought this philosophical concept to bear upon the concrete world of contestation and exploitation, explaining how what appears is underwritten by something more complex and systemic. As one reads Azfar Hussain's Dorshonakkhyan, one is obliged to take into account the significance of the relation between the book's philosophical/aphoristic form and its compelling political content.The short meditative paragraphs that communicate abstract ideas are loaded with implicit and explicit discussions on social inequalities. The quasi-theological contemplations reflecting on existence are vignettes under whose frames lark penetrating anti-colonial critiques that simultaneously alert readers about the failures of western positivistic thought and about our own inability to inhabit a radical space when we confront colonial knowledge and power. Azfar Hussain's Dorshonakkhyan is not simply another mundane work hiding behinda shiny book cover; it is one of the finest specimens of philosophical thought in Bangla language which solicits us with its political content. Anyone interested in theory and criticism will find this book both provocative and worthy of attention.

Divided into eight chapters that explore eight different concepts, Hussain's micronarratives engage with trivial and commonplace materials/conceptual things like language, silence, place, map, soap, narrative, smell and dot to show how these familiar things/ideas exist as complex symbols in an overdetermined world. Most chapters begin with deep philosophical meditations and end with poetry, connecting philosophical thoughts with aesthetic experience. One of the clear projects of the book is to undermine the line of demarcation between philosophy, politics and aesthetics. Dorshonakkhyan's restless navigation between different disciplines and genres is an attempt to undo the rigid disciplinary boundaries we strictly follow and fetishize. Every chapter of this book is an interdisciplinary take on commonplace but deeply significant things. Poetry, mathematics, theology, ethics, politics, fiction, linguistics exist in this work as mutually constitutive concepts, in conversation with each other. Despite Dorshonakkhyan's formal and thematic interdisciplinarity, however, what constitutes the ideological core of the book is revolutionary politics. Dorshonakkhyan enacts not only a political economy but also a political philosophy and suggests that the purpose of knowledge is not only to critique oppression and inequality but also to resist them.

Take, for instance, its first chapter titled 'Bhasha' (language). This chapter begins with two epigraphs on the question of language: one by Marx (and Engels) and the other by Gramsci. The first micronarrative alerts us about the difficulty of finding answers to some of the most fundamental questions about language. What is language? What is its abode? What are its destinations and limits? These questions are difficult to answer because neither history nor reality accords us enough clarity to understand the abstract truth of language's being. Questions about the being of language, Azfar Hussain tells us, do not need to be approached from a singular direction. One can also begin from the premise of language's social being: how language operates in society. What follows from this philosophical premise is the political economic understanding that language's existence in society is mediated by production relations. 'Language,' writes Azfar Hussain, 'comes steeped in the dirt of production relations.' This is how the philosophical query into the being of language turns into a historical materialist interpretation of the existence of language—an interpretation that tells us that the being of the language cannot be understood froma purely philosophical standpoint.One cannot hollow out history and material life from language and seek to posit it as an abstract concept unscathed by either life or time. As Azfar Hussain reminds us, language exists as a mediator but that mediation itself is historically and socially mediated. Linguistic mediation, in that sense, is a tripartite mediation between 'the self and consciousness, between consciousness and the material world, and between material world and the self.' From this philosophical premise, the narratives then spill into other dimensions of language's existence, discussing how language both conceals and reveals class-race-gender-national struggles. The chapter on language ends with an excellent translation of the Spanish poet, Vicente Aleixandre's poem 'Después del amor,'—a poem that explores the relation between language and the body. Language, after all, is an embodied expression, existing in relation to other material and immaterial sites that dialectically relate to it and interact with it.

One of the most unusual chapters of this book is an autobiographical meditation titled 'Akkhyan' (narrative). In it, the author recounts how a day-long trip to listen to a lecture by French deconstructionist philosopher Jacques Derrida turned into a harrowing experience of witnessing intellectual evasiveness. Derrida's four-hour long discussion on typewriter ribbon and ink, we are told, is a classic example of how alienated intellectuals cover the actually existing injustices through surfeit of words and language games. Those who can powerfully employ narratives themselves are often oblivious to the consequences of their intellectual apathy. The plain truth about human suffering—racial, colonial, gender, sexual, and class oppressions carried out by economically and politically powerful people against the less powerful ones—appear vague and equivocal because intellectuals lose sight of concrete lived experience. Azfar Hussain draws attention to intellectual evasiveness through this personal narrative, reminding us that seduction of abstract ideas led postmodernist and post-structuralist thinkers towards a self-referential textual politics which failed to create a better world.

The other chapters, much like the ones mentioned here, are also intricately composed. They discuss a whole range of philosophical and political issues, from the Cabbalist concept of words and articulations to the colonial/racial politics of soap and purification. Many of these micronarratives are insightful and politically charged, while a few others, as is supposed to happen in a book like this one, do not have the same level of intensity and finesse. The chapter on smell is not only short but also relatively less meticulous, while almost every other chapter is penetrating and incisive. What binds all these narratives together is a powerful critique of various forms of oppressions that exist today. Dhorshonakkyan's premise is unmistakably Marxian, although stylistically it follows an eclectic path, combining short narratives with poetic, autobiographical and fictional accounts.

Besides its historical materialist philosophy, the true achievement of the book is its language.Written in crisp and clear prose, Dorshonakkhyan's rigor comes as much from its thematic content as it does from its language. Although philosophical, Azfar Hussain's book is never dull because of his captivating prose that pulsates and changes its cadence according to its subject matter. Very few people writing in Bangla can muster such powerful prose which transmits the author's emotion into the reader, communicating at a level rarely seen in case of theory and philosophy. When the fashion among theorists is to hide behind their language, Azfar Hussain chooses directness and simplicity over opacity; but what is remarkable is that he does so with a poet's creativity and liveliness, which makes reading his work an engaging enterprise.

Those who have been following the author for a long time will find some of these micronarratives familiar. As is acknowledged in the book's preface, five of the eight narratives were published almost a decade ago when the author was simultaneously writing for an English daily a longer series of narratives titled 'Micronarratives.' Most of the chapters included in the current book were printed in a daily newspaper published in Bangla. In that sense, the book's subject matter is not entirely new. Despite some people's familiarity with the book's thematic content, we need to feel excited by Dorshonakkhyan's arrival amidst us because this book's significance far outweighs our familiarity with it. We ought to celebrate every time a good book is published because every good book is a reminder of our potential. In an era of darkness when both knowledge and philosophy are under assault—when we demur the absence of decency and courage—Azfar Hussain's Dorshonakkhyan gives us hope. This 151-page book has more to offer than may appear at the beginning, when we set our sight on it. Reading it will challenge our understanding of the world. Not many books published today can aspire to do so.

Hasan Al Zayed teaches at the University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh and is a PhD Candidate at State University of New York, Albany.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments