On Children’s Literature in Bangladesh: Then and Now

I can't remember the last time I'd read a children's book. I believe the book in question was Meku Kahini (Anupam Prokashoni, 2006), an all-time favourite, but I can't bring myself to recall the time. That's how old I am. When I realised World Children's Day was fast approaching, I decided that I owe it to the child in me to write a small tribute in memory of the books that got me into reading in the first place: children's books. I read everything from Enid Blyton and Roald Dahl to Satyajit Ray and Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay, Rabindranath Tagore's Icchepuron from his Galpaguchchha (1939) collection being my first foray into children's literature.

I thought I'd ask some of my peers about their favourites from childhood. There were a lot of 'Satyajit Ray's, but they were all eventually drowned out by the cheers for Humayun Ahmed and Muhammad Zafar Iqbal. The response seemed to mimick the transitions in Bangladeshi readers' tastes themselves, which had once moved from classics to contemporaries. For most of the 20th century, children's literature in Bengal relied heavily on raw Bengali humour and small-town stories. One need not look further than the successes of the Ray family or the comic strips created by Pran Kumar Sharma and Narayan Debnath.

Post the 1990s, however, the pre-adolescent audience seemingly began to long either for more Dhaka-oriented stories, or those inspired by foreign landscapes. Humayun Ahmed and Muhammad Zafar Iqbal rose to the occasion beautifully. Tastes changed, as did the popularity of the children's books in our country, with novels and short stories such as Dosshi Kojon (2004), Neel Hati (2010) and Tomader Jonno Rupkotha (1988) trumping over the Feluda series, the Akbar-Birbal stories, and the Nonte-Fonte comics.

"When I was a kid, all I found in bookstores were Bangla translations of popular fairy tales from abroad, Cinderella for example. Children's books of quality content penned by local authors were difficult to come by. It felt as though the writers couldn't be bothered to be more original," bookstagrammer Shehrin Tabassum Odri shared with me. Yet another reader, Raisa Bashar, confessed that she enjoyed reading Bengali translations of Tintin comics as a child. "When I read an English Tintin for the first time it just felt really dry. I think there's a certain charm to reading works translated in Bangla, with the characters being made to appeal to a Bengali palate," she told me.

"All that a school-going child needs to boost their imagination is a good book. That is where her minds begins to be shaped," I was reminded by Ekushey Padak-winning children's author and playwright Farida Hossain last night over a phone call. Writing since her own childhood in the 1940s, Farida Hossain had put in a significant amount of effort into popularising children's literature all over Bangladesh with the help of the silver screen. She wrote, directed, and composed the musical score for a fairy tale series for BTV, called Rupkothar Deshe, in which seven children of the sky, each representing a colour of the rainbow, flew around to save the day in different parts of rural Bangladesh. When asked about what could be done to diversify children's literature for the audience, the author spoke in favour of more extensive research in the genre.

Today, however, independent publishing houses have another struggle to overcome: how to attract young readers whose eyes are glued to the LCD screens? How to make sure no child is being left behind?

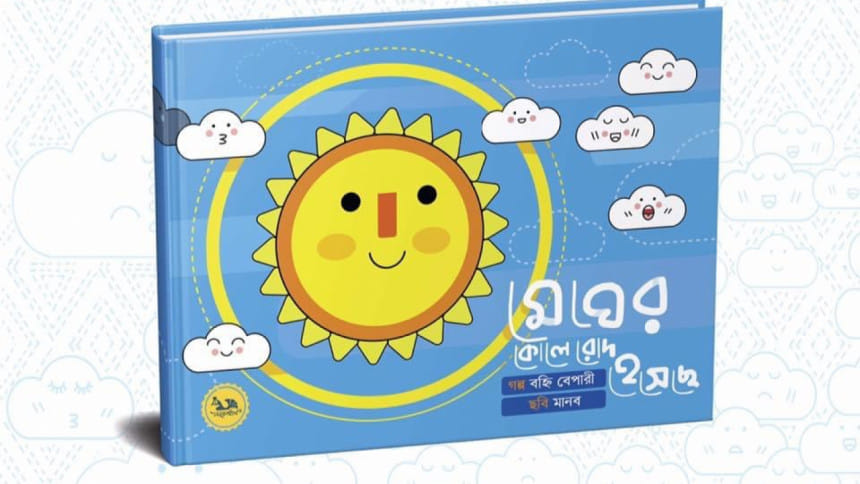

To answer the first question, Mayurpankhi publishers started their journey in 2014, with a goal to keep children invested in books through quirky illustrations and strong social messages. CEO Mitia Osman spoke to me about their goals to reinvent children's literature in Bangladesh by combining visual art with contemporary literature. "We want to introduce a fun way of teaching moral values and ethics to Bangladeshi children," she shared. Mayurpankhi specialises mostly in beautifully illustrated picture books, such as Megher Kole Rod Heshecche (2020) which is a short story exploring interactions between the sun and the clouds, and Amar Bhasha (2020) which acts as a children's guide to understanding the Bangla language.

Meanwhile, writer and motivational speaker Nazia Jabeen launched Sporsho Braille Publishers in 2009, to promote inclusivity in reading for blind individuals. Nazia Jabeen herself refrains from referring to visually impaired people as 'blind', choosing to address their strengths instead as people who have 'transcended the power of sight'. The author discusses the braille books that have been published at Sporsho saying, "We try our best to ensure the content of our books is sensitive towards the sentiments of children whose loss of sight may have been the topic of scrutiny in our community. They're all kids at the end of the day who need to understand how to empathize with people and be kind towards the world itself." Due to their focus on Braille books, a largely foreign concept to Bangladesh, Sporsho's journey hasn't been an easy one. It took the team years to help Bangladeshi citizens and mass media understand the necessity of their content, and the sheer amount of work that goes into producing them. The production costs of braille books are thrice as much as that of a regular book, and without much support, the organisation struggled a lot during their early days in 2009. But as more people began to understand braille and its significance in children's books, the warmer the audience reception grew towards Sporsho's published titles which include the works of reputed authors such as Selina Hossain, Muhammad Zafar Iqbal, Faridur Reza Shagar, Hanif Shanket, and many more.

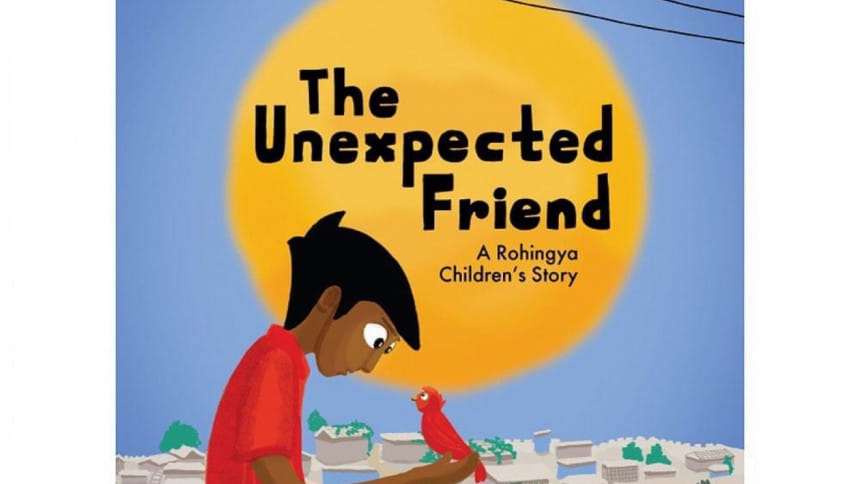

Children's literature in Bangladesh has largely failed to adapt to their audience's constantly evolving tastes, rendering the genre incapable of retaining a loyal fan base. However, in recent times, attempts are being made to breathe new life into Bengali children's books. Mom blogger Samira Ahmed, popularly known as The Millennial Ma, compliments Guba Books, Bok Bok Books, and Mayurpankhi on their efforts to reach the Bengali diaspora all over the world, which she herself, as a UK citizen, has been a satisfied recipient of. The aforementioned publishing houses offer a wide range of easily-accessible, bilingual books for Bangladeshi children living in foreign countries. Notable bestsellers include Bok Bok Books' Dhobdhobe O Kuchkuche (2019), Guba Books' The Unexpected Friend: A Rohingya Children's Story (2019), and Mayurpankhi's Jhumi Elo Chiriakhanaye. Speaking from personal experiences, Samira Ahmed shared, "I'd love to see more inclusivity and diversity across all children's books. We need an emphasis on love that transcends borders, races, and religions. I'd also love to see an end to gender stereotypes. Little girls can be more than princesses and little boys can be emotionally vulnerable."

For our little ones, books collectively make up that window through which they see the outside world, its flaws and its glories. It's only fair that more effort should be put in to make sure their minds receive the nurturing they deserve.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments